The Art Detective

How David Zwirner’s Click-to-Buy E-Commerce Company Evolved From a Goodwill Project Into a Money-Making Machine

The company says it has sold around 50 percent of the 282 artworks it has offered in its first three months.

![Platform's leadership team [L to R]: Marlene Zwirner, Lucas Zwirner, and Bettina Huang. Photo: Martyna Szczesna. Platform's leadership team [L to R]: Marlene Zwirner, Lucas Zwirner, and Bettina Huang. Photo: Martyna Szczesna.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2021/05/2.-Marlene-Zwirner-Lucas-Zwirner-Bettina-Huang_Photo-by-Martyna-Szczesna-683x1024.jpg)

The company says it has sold around 50 percent of the 282 artworks it has offered in its first three months.

![Platform's leadership team [L to R]: Marlene Zwirner, Lucas Zwirner, and Bettina Huang. Photo: Martyna Szczesna. Platform's leadership team [L to R]: Marlene Zwirner, Lucas Zwirner, and Bettina Huang. Photo: Martyna Szczesna.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2021/05/2.-Marlene-Zwirner-Lucas-Zwirner-Bettina-Huang_Photo-by-Martyna-Szczesna-683x1024.jpg)

Katya Kazakina

The Art Detective is a weekly column by Katya Kazakina for Artnet News Pro that lifts the curtain on what’s really going on in the art market.

You may have seen the ads on Instagram. There’s a graphic logo and, in clean font, the tagline: “A new way to buy art.”

The millennial-friendly e-commerce company Platform has, over the past three months, sought to expand the audience for emerging art by partnering with a select number of small and midsize galleries. The initiative is not a scrappy start-up founded by recent college grads—it’s backed by David Zwirner, one of the biggest and most established galleries in the world.

Online sales boomed during the pandemic despite the contraction in the overall market, reaching a record $12.4 billion in 2020, doubling in value from the prior year, according to the annual art market report by UBS and Art Basel. For galleries, the share of online sales tripled to 39 percent in 2020, although the majority of transactions involved existing clients, the report said. It’s no wonder that several startups, including Platform and Johann Koenig’s MISA, are now focusing on growing new audiences. They join existing competitors such as Artsy and Saatchi Online, among others.

Since its official launch in May, Platform has resisted sharing any details about its reception—until now. To date, the click-to-buy e-commerce business has featured 36 galleries, 72 artists, and 282 artworks, priced from $2,500 to $50,000. About 50 percent of the pieces have sold (a solid total of around 140 works) and 11,000 people visit the website daily, according to Bettina Huang, Platform’s general manager.

A lot remains unknown. The company declined to reveal its sales and revenue figures, saying they were proprietary. (By our own calculators, based on the number of works offered and the price range, Platform’s cut could range from $24,000 to $440,000 per month.) It hasn’t shared much information on clients with the participating galleries, including the names of those who joined waitlists for artists, citing privacy laws.

While some galleries grumble about the lack of cooperation on this front, many have been pleased when it comes to sales and exposure.

“It’s great visibility for the artists,” said Allegra LaViola, owner of Sargent’s Daughters gallery in New York. “Things sold. Why not?”

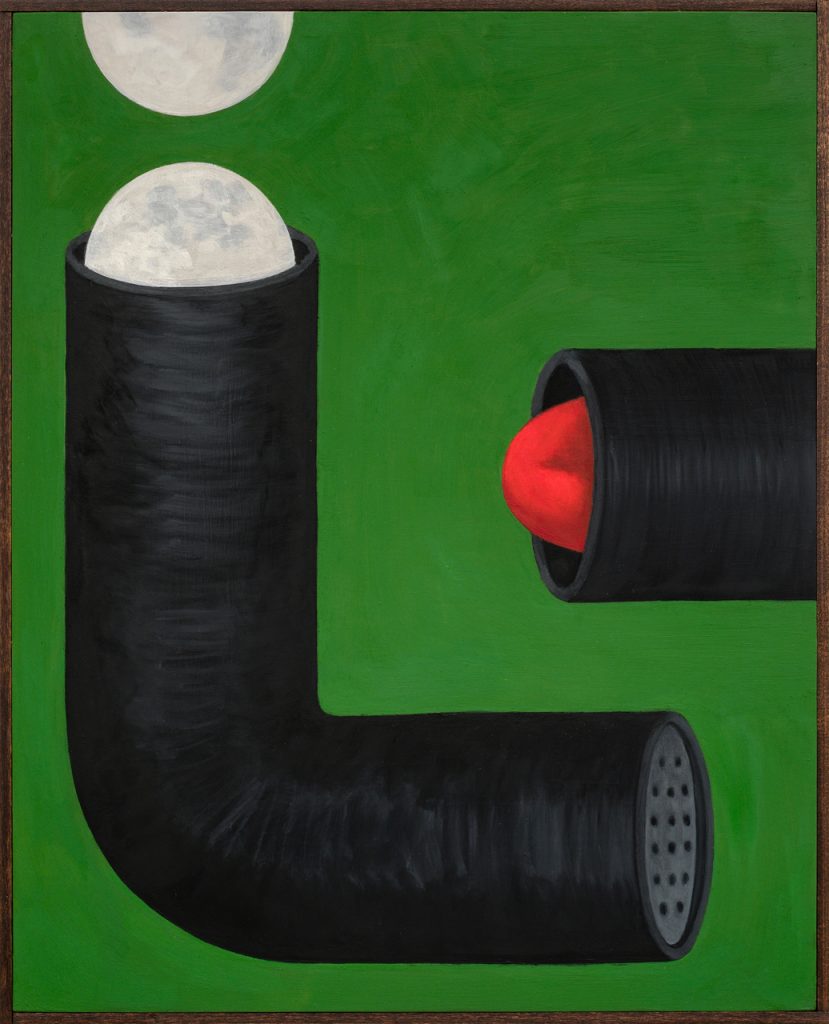

Emily Furr, Moon Grinder (2021). Courtesy of the artist and Sargent’s Daughters. Photo: Platform.

Platform was conceived early on in the pandemic as a charitable initiative to help midsize galleries at a time when art fairs, their major source of revenue, had been cancelled indefinitely. The only way to survive was to quickly pivot online. But many smaller galleries didn’t have much in the way of digital sales infrastructure—or the capital to support it.

Zwirner, on the other hand, had been relatively early (at least among galleries) to realize the importance of the Internet, launching a virtual viewing room in January 2017 and building out the gallery’s offerings with special presentations for art fairs, exclusive online shows, and virtual fundraisers.

When lockdowns began, Zwirner created a digital sales platform and offered it free of charge to smaller galleries in three cities: New York, London, and Los Angeles. Sales totaled $1.2 million, the gallery said at the time.

Today, Platform has evolved from a gesture of goodwill into a business. Here’s how it works: The team selects 12 galleries to present eight works by two artists (that’s 96 works total). A new batch drops each month. There are no discounts. No haggling. Platform takes a 20 percent commission from each sale, right off the top. The galleries and artists split the rest.

Lucas Zwirner, the son of the gallery’s eponymous founder and a lead on the project, sees Platform as an alternative to the regional art fair. As much as galleries depend on these trade events, they also love to hate them. They require huge expenditures and demand a life on the road (not to mention their negative environmental impact).

American’s shopping habits continue to migrate online, brick-and-mortar stores across the country are closing at an increased rate. Photo: Spencer Platt/Getty Images.

“If you think about a regional art fair, it costs a gallery $25,000 to $50,000, potentially,” Zwirner said. “That’s a lot of risk to take on to go to Dallas, to see how much inventory you are going to sell, which you might have to ship back. If you go to a regional fair, you sell 20 percent to 30 percent of your inventory.”

While big fairs draw a top-quality audience and create a sense of urgency that’s hard to replicate in other settings, Zwirner says that COVID helped show galleries that there might be an alternative to the frantic and endless merry-go-round of art fairs.

Platform uses newsletters, original content, and social-media advertising to attract a younger, e-commerce savvy audience that may never have bought art before. (It declined to provide any numbers on its distribution lists.)

One way to convert art-buying newbies into art lovers is to create a seamless shopping experience that feels safe and familiar. “The reality is that there’s so much low-hanging fruit that already exists in other industries that still hasn’t been properly adapted and adopted to the gallery model,” Zwirner said.

Bettina Huang, who was previously head of consignments at Artsy and head of merchandising at Fab.com, began with a fundamental premise: to embrace the way people shop today. “We are very intentionally bringing them an experience that’s familiar and that they expect when they’re shopping any category online,” she said.

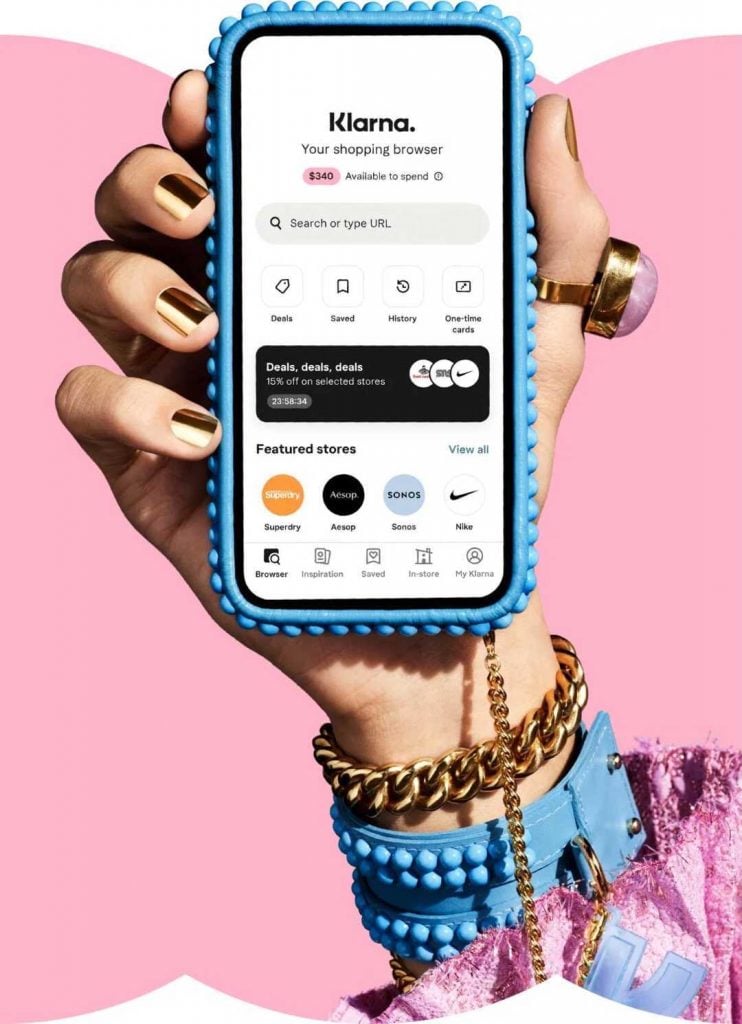

This month, for example, Platform began a partnership with Klarna, a company that allows consumers to pay in installments for luxury items and household goods. “Why should you have any different experience buying art than you would buying a luxury item?” Zwirner said. “Many young consumers, 30 and under, want to pay over time.”

Klarna’s user interface. Courtesy of Klarna.

Browsing through Platform the other day, I clicked on a photograph by Robert Sandler that depicted a clown devouring a pile of spaghetti, priced at $2,500. A little button on the right side offered to show me how to pay for the work in four $625 payments.

Price transparency is another core value. “You don’t have to inquire and negotiate with someone, who then gets to choose whether or not to sell to you,” Huang said. “You add to cart and you check out.”

During checkout, customers get shipping and insurance quotes instantaneously. They can return a work of art within two business days of receiving it. “You’re seeing it in person for the first time when it arrives in your home,” Huang said. “So, we really need to give customers comfort that way. But the really great thing is that we’ve had no returns.”

Robert Sandler’s Domestic Clown I (2020) featured on Platform with Klarna payment installments. Screenshot courtesy of Platform.

For art dealer Charles Moffett, the reach and association with David Zwirner was valuable enough that he was willing to give up a percentage of sales “even though those were the works we could have easily sold on our own.”

Deciding what to consign is a nuanced, often protracted, process. Platform mostly wants popular artists, according to participating dealers, and often asked for new pieces to be created especially for the site.

“They looked at everything,” LaViola said. “We went back and forth on which artists, which works by the artists.”

She ended up consigning four surrealist paintings by Emily Furr. They sold quickly at prices ranging from $2,700 to $5,500. Three out of four representational paintings by Brandi Twilley are still available. Moffett presented eight works by Lily Stockman and Kenny Rivero, all of which sold.

Beyond immediate sales, the biggest question is what data Platform shares with its gallery partners and how it might help them grow their audience. The answers are inconclusive.

Right now, if a work is already sold, customers can add their names to a waitlist. Those names aren’t shared with the galleries, dealers said, though some people have reached out directly. “It would be nice to understand a little bit more about who’s coming to our artist pages and looking at the work and voluntarily registering the interest,” Moffett said.

The homepage of Platform, featuring a work by Travis Boyer. Screenshot courtesy of Platform.

A spokesperson for Platform previously stated that client information and sales data cannot be shared with anyone—including David Zwirner. But when “a sizable number of waitlist inquiries on works by a specific artist” accrues, the company reaches out to the galleries representing the artists to see if they have additional inventory that they would like to add. People who had put themselves to the waitlist are then alerted, resulting in additional sales.

The swift adoption of Platform among galleries is a testament to what makes the art market unique—disruption is more likely to come from a company already at the top than from an outsider upstart. “The reason why people were interested and excited to do it is because of its association with David Zwirner,” LaViola said. “It’s a tacit endorsement of you and your program.”