The art world knows one word, above all others, and that is “no.” No, you can’t buy this (the illusive waiting list); no, you can’t do that, or say… just about anything. In the case of Art Basel Switzerland, marking a return to some degree of normality in the international fair arena, a band of dealers fearful of weak attendance and sales, spearheaded by Lisson and joined by Acquavella and many others, initiated a campaign to cancel the event before it even got off the ground after a spate of Covid-related cancellations. In retrospect, I bet they are heartened that they failed in their attempt.

By all accounts, Art Basel was a success—not a runaway, out-of-control selling orgy as in previous years—but a steady stream of solid, if modest, results. This was in spite of the fact that there was, according to one participating gallerist, only 60 Americans and virtually 0 Chinese collectors on hand (the lack of Americans was actually celebrated by Belgian collector Alain Servais). A top L.A. dealer told me they made more money in the last year than in any of the previous 25-plus years they’ve been in existence, due to lower expenses for shipping, traveling, and fair admissions. Yet, for the intrepid few who made the trip, restaurant reservations and a coveted room at the Three Kings Hotel remained elusive.

Noticeably absent from the proceedings were stalwarts Larry G. and Matthew Marks, among others from the U.S. who chose not to cross the Atlantic. Of the gallery proprietors who did choose to join, most were gone before the end of the week. When asked for a quote on the first day of a series of staggered openings, Marc Glimcher of Pace (on the floor, sans père) without missing a beat, replied: “The death of the art fair is greatly exaggerated.”

Glimcher reported rapid sales in excess of 25 works, including a Jeff Koons gazing ball painting for $1.5 million. Of note, in relation to Koons and other artists on hand, such as Joe Bradley, primary prices were significantly reduced from the recent past—for Koons, by as much as 33 percent. Watch for Jeff himself to dip into the NFT fray with a work inaugurating Pace’s new platform. I can’t wait for his syrupy/new age/self-actualized explanation of the medium!

Crypto Kiosk at Nagel Draxler Gallery in Basel. There’s always a first, and this is it for art fairs and NFTs—what is surely the first of many.

At the time of this writing, Matthew Wong, who died two years ago (the estate is now handled by Cheim and Read), and who is the subject of a museum show at the Art Gallery of Ontario, had a painting sell for $1.75 million and a work on paper for $375,000. Another painting by the artist is on hold for a major international institution at $2.75 million. Next up for my dear friend Matthew is an upcoming exhibit at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum.

Thomas Dane Gallery sold a secondary Albert Oehlen painting for $2 million, a small Cecily Brown canvas for $450,000, and Dana Schutz watercolors flew at $80,000 each. Carol Greene of Greene Naftali had brisk sales for paintings by Jacqueline Humphries and Walter Price, priced at $500,000 and $80,000, respectively. Nahmad Gallery had perhaps the biggest sale of Basel, a Picasso for under $20 million, a sign of the lowered temperature in the age of the ongoing Covid crisis.

Unsold (when I last checked) were works by Robert Ryman at Zwirner, including a large $28 million piece that has been exposed on the market over the past years, but still a flex after luring the artist’s estate from Pace, along with his long-term representative at the gallery ,Susan Dunne, who left after accusations of fostering a toxic work environment. A Basquiat offered by Van de Weghe was still there for the taking at $40 million, in spite of being shopped by owner Bruno Bischofberger at the significantly higher price of $50 million to $60 million, according to a dealer in the know (who happens to lie less than most in her position). And Skarstedt hadn’t yet parted with a killer Martin Kippenberger self-portrait for €7.5 million ($10.2 million), nor paintings by Richard Prince and Christopher Wool.

A last tidbit of old world art market gossip: A group of 29 works in Christie’s November evening sale titled “Image World,” which “celebrates” (I guess cashing in is a form of making merry) pioneering artists of the Pictures Generation such as Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Richard Prince, and Christopher Wool, among others, is being flogged from the collection of Cynthia and Abe Steinberger, who simply decided to move on, and have disinterested kids, I suppose.

Art Basel 2021 could have passed for a mid-century exercise in conservative dealing such was the preponderance of flatworks, i.e. paintings, and thinness of art employing technology. My luck, Basel Lite (fair aisles minus the bustle) transpired when I curated an NFTism™️ show—you can thank my lawyer, Gale Elston, for the trademark—for Nagel Draxler Gallery, entitled Crypto Kiosk, the first of its kind at a semi-major (this go-round) international art fair. On the upside, smack in the middle of a slew of galleries having cancelled their Art Basel Miami plans, the U.S.A. did an about face ending its non-reciprocal, head-in-the-sand position of closed borders to Euro travelers, so most galleries had a change of heart mid-stream in Basel and decided to attend. Thankfully, Nagel Draxler will now proceed with its Miami participation, which will feature a more ambitious NFT outing that I am helping organize. Look for Miami to be inundated with crypto folks, including the fair itself, which will dive into the craze.

The line around the block in London at the opening of Institut’s “NFTism: No Fear in Trying,” the world’s biggest NFT show to date.

On the eve of Basel Switzerland, I curated the largest NFT exhibit to date for the inaugural collection of Institut, an upstart platform in London for which there was a line extending around the block to attend the opening (the initial auction ended yesterday). Hauser and Wirth is about to launch a new site and Gagosian is undergoing exploration of its own incursion into selling NFTs. These efforts are hardly an instance of innovation on the part of galleries, their market hegemony is being threatened—it’s eat or get eaten. Creators can just as easily forego galleries and engage direct-to-market, selling their art with little fanfare via their own websites coupled with established marketplaces like OpenSea, which did $3.5 billion in business in August alone, compared to a total of $2.4 billion during the first quarter of 2021.

Resale royalties baked into smart contracts in perpetuity are an artist’s wet dream. Rather than pumping up primary prices to the highest level sustainable, it pays to lure new buyers with seductively low prices coupled with a long-term view as to how things will pan out. I never thought I’d live to see a time when flippers would lose their pariah status and be all but lauded.

I own eight works by artist Calvin Marcus, who I admire and have the utmost respect for, the majority of which were purchased five years ago. I decided to part with a painting in order to help pay for the purchase of a house, and after consigning the work to auction, I got a call from the disgruntled dealer I bought it from who wasn’t amused. But is it not my prerogative and within reason to do so? If there was a resale clause benefiting the artist, which in the case of NFTs is a trustless contract that requires no human interaction to enforce (it’s effectuated on the blockchain), there would be no conversation.

Me and OG NFT influencer and investor G Money talking shop, and at my age!

Flamingo is an NFT collection structured as a Decentralized Autonomous Organization (DAO, pronounced “Dow”; I want to start one called Dow). As I predicted the onslaught of NFTs last year, the same applies to DAOs, which stand to overturn the preexisting structures of corporate governance and issuance of shares in the future.

As stated prior to the launch on October 8 (when Ethereum stood at $350 per): “Flamingo membership will be on a first-come-first-serve basis. Each member will have the opportunity to contribute 60 ether to receive a 1 percent interest in Flamingo, which entitles a holder to 1 percent of Flamingo’s voting rights and profits. Membership is limited to a maximum of 9 percent or 540 ether per member.” Flamingo has a current valuation approaching $1 billion with a single Crypto Punk (Alien) in the portfolio, purchased for around $700,000 earlier this year, and currently valued in excess of $50 million.

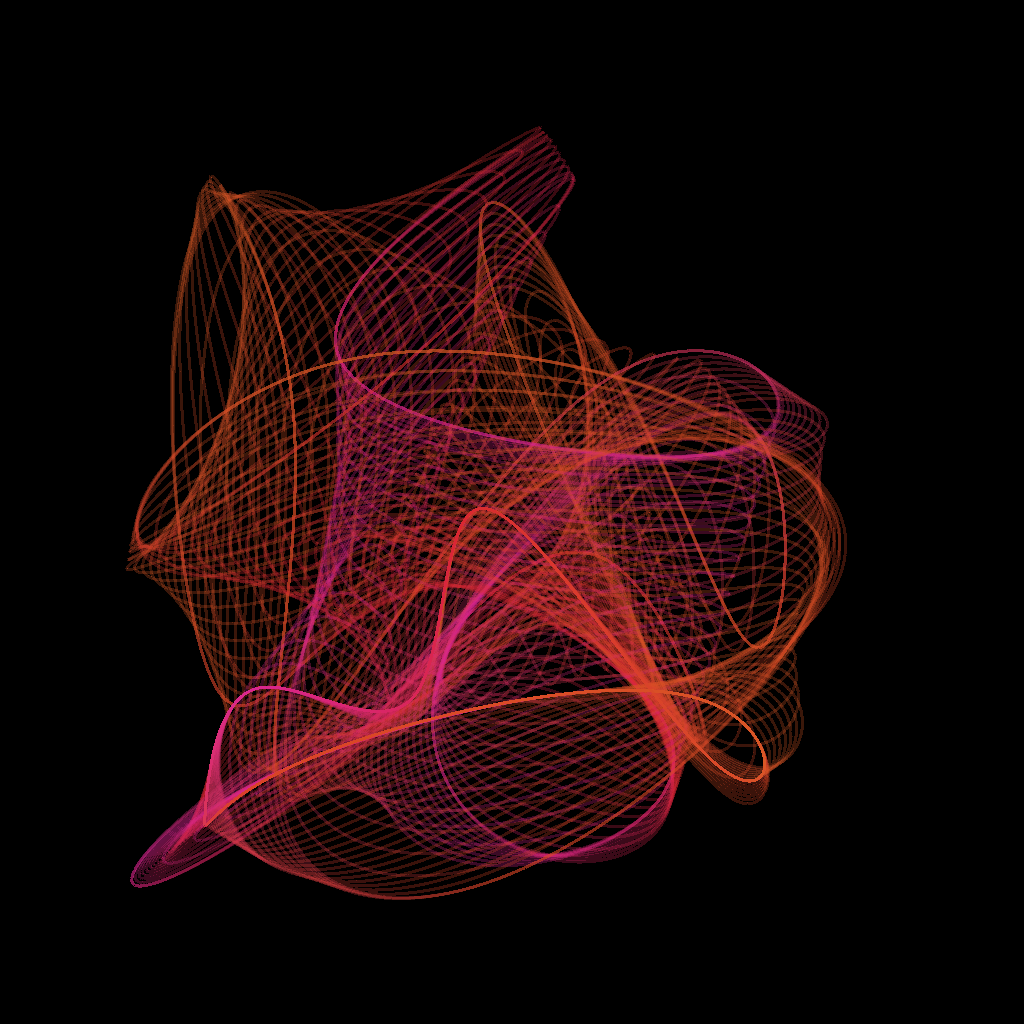

The artists go to bed broke and a few years later wake to a million or two in their wallets. It could only happen in the land of NFTism: klee02 by Kelian Maissen and Johannes Gees.

Here is another interesting tale (of too many to reiterate) in crypto-land: “kleee02 is an art piece by Kelian Maissen and Johannes Gees. It is a contemporary, blockchain-inspired take on conceptual art. The kleee02 smart contract was uploaded to the Ethereum blockchain on April 10, 2019, making kleee02 one of the ‘oldest’ NFT projects.”

To reiterate, tech-time turns Einstein’s special theory of relativity upside down, conflating the rate of change with head-spinning velocity. The klee02 was inspired by Klee’s quote that “a line is a dot that went for a walk”. The project had an inauspicious start, flatlining for a few years before other projects simultaneously rocketed to the moon price-wise, like Larva Labs’ (the Crypto Punk founders) Autoglyphs, surpassing $1 million per. Gees has been working with abstract biomorphic light projections for decades without much love from the art world as we knew it. One recent morning the pair awoke to an astronomic rise in the value of their NFTs years after the fact, but bugs in their initial smart contract caused hiccups requiring refunds to buyers. When all was said and done, the pair still managed to reap rewards neither had dreamt of—and resale rights keep the windfalls flowing.

With the advent of Profile Picture (PFPs), NFTs minted in series of 10,000 that began with Larva Labs’ Punks, I had the notion to start an on-chain arts club with a relatively low barrier of entry—around $80 at the time. The idea was to satirically call them Crypto Mutts (as a self-taught outsider, I’ve always considered myself an art world mongrel) poking fun at the plethora of such projects comprised of dogs, cats, apes, punks, unicorns, bunnies, penguins, etc. It was intended that each NFT in the run would constitute entrée to my writing and other swag and rewards like t-shirts, NFTism tokens, and subsequent NFTs airdropped for free into holder’s accounts. Without fanfare, I offered Mutts for sale at 7 p.m. on September 21 from my hotel in Basel, the same day the fair opened. Within an hour or so, 9,000 Mutts had sold out. At the tender age of 59, I became an overnight NFT phenom. Within minutes, there were fake Mutts on offer, surely a sign of success.

My life hasn’t been the same since. The first order of business was to start a Discord chat room (thankfully not owned by Zuckerfuck), the social media of choice after Twitter for hardcore NFTists, founded by social gaming developers Jason Citron and Stan Vishnevskiy. This took some getting used to, finding my rhythm to communicate with fellow Mutt holders, and it’s been a long trip down an Alice in Wonderland wormhole ever since, which I find exhilarating and addictive—just what I need at this juncture in my life. I have always said—in the past year anyway—NFTs are nothing, but NFTism is the community that has rapidly developed in relation to the digital art arena. The Mutt community is already close, caring, and prodigious in their supportiveness; something you find in short supply for the most part in the old art world.

I wouldn’t want to be a member of any club that would have me. Except for this one! Meet the Mutts.

I haven’t had a real job since law school and consider myself all but unemployable, but now I find myself answering to the 2,000 bearers of my NFTs, one of whom, as the owner of a few hundred, refers to himself as the Mugrabi of Mutts. The actual Mugrabis own an official Warhol NFT, 17 Tom Sachs Rocket Factory NFTs, and others. Perhaps it’s naive, but my intent is that some of those that come into the Crypto Mutt project reductively looking to make a quick buck (or rather, some ETH) will end up liking a wider range of art than they did coming into the enterprise. Stranger things have happened.

If I hear one more person declare they want to build a nexus between the traditional and digital art worlds, I will blow that bridge (and myself) up. OK, I’m exaggerating, and to some extent, in essence, I am the personification of that conduit. I’ve spent a sizable chunk of the past three-plus decades learning about art, which is a slow-burning process of accruing information and knowledge. It’s been joyful and there’s no finish line, which I especially like. By the same token (I couldn’t resist), NFTism is a universe unto itself with its own language and ways and it’s typical art world hubris and arrogance to think they could crack it as soon as they saw dollar signs without the requisite investment of time and effort (a lot) to understand the ins and outs of crypto.

If the traditional art world wants to fully engage, and this is well underway, we need to vanquish our old ways of thinking to appreciate and comprehend the extent of this new world order. I can’t wait—and, for that matter, I no longer have to.