Kenny Schachter

Filmmaker James Crump Dishes to Kenny Schachter About Why Making a Movie With Jordan Wolfson Was a Total Nightmare

Kenny was very curious about why the two no longer speak.

Kenny was very curious about why the two no longer speak.

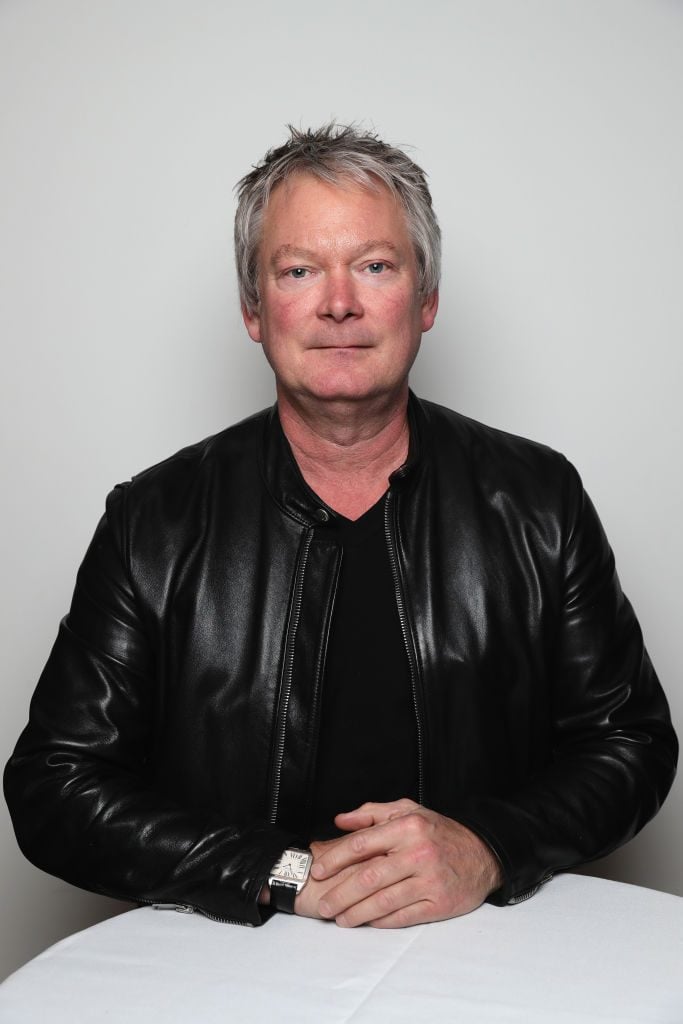

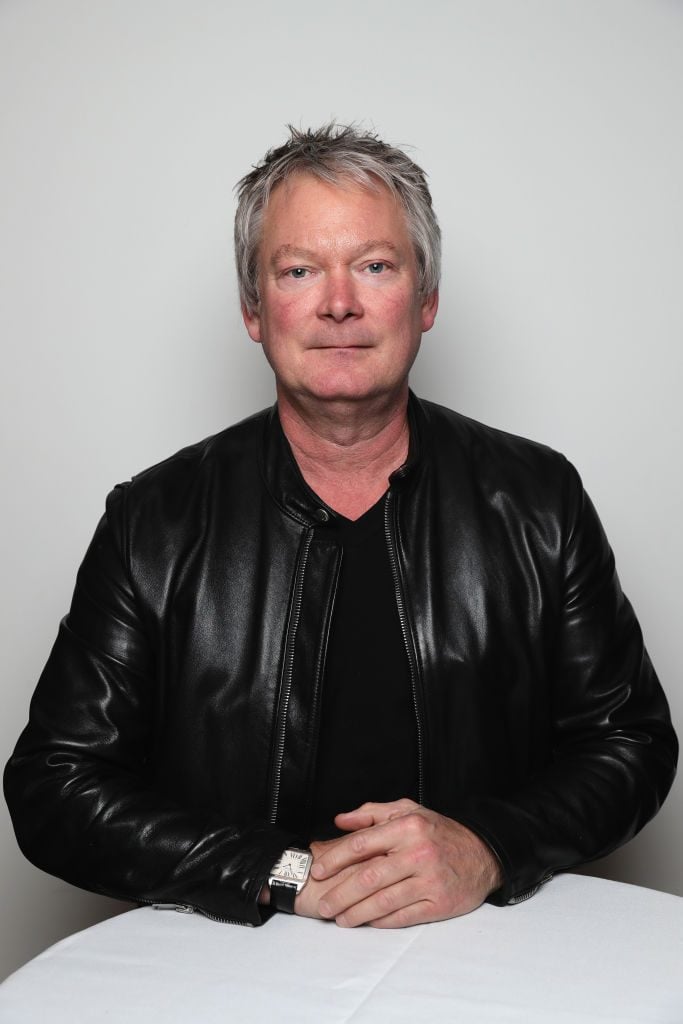

Kenny Schachter

You know James Crump. He made an action movie out of the largely stoic lives of Land artists (Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art) and single-handedly brought to life the all-but-forgotten heroics and artistry of fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez (Antonio Lopez 1970: Sex, Fashion, and Disco). That’s not even to mention his compelling film on Mapplethorpe and Sam Wagstaff (Black, White, and Gray: A Portrait of Sam Wagstaff and Robert Mapplethorpe).

Most vividly, he crafted a somewhat disturbing psychological profile of mercenary video and installation artist Jordan Wolfson that ended in conflict and controversy for both subject and filmmaker. My kind of documentary (especially because I featured in a supporting role).

James Crump and his producing partner, Ronnie Sassoon, in Marcel Breuer’s Stillman House II, which they own, in Litchfield, Connecticut. Photo: Martyn Thompson, courtesy James Crump.

The latest in Crump’s filmic series is another deep dive, this time into the architectural practice of Marcel Breuer and—more tellingly—the lives of a coterie of patrons in a tiny town in Connecticut that had an outsized and formative role in the development of the architect’s output and career.

I must say, the freewheeling sexual proclivities—some more deviant that others—practically steals the show. You’ll have to watch for yourselves, I won’t ruin it for you. Until then, here’s your chance to see a snapshot of the director himself and his fantastic producing partner Ronnie Sassoon, and find out for yourselves how the wolf in Wolfson came into being.

(For the record, Wolfson told us that Crump’s below claims about him “are not true. When the film was completed and after seeing it, I was shocked at how it misrepresented me and others so I told James Crump I wouldn’t support the film. In correspondence with me, he made it clear that having a negative relationship with me would be beneficial for the promotion of the film.”)

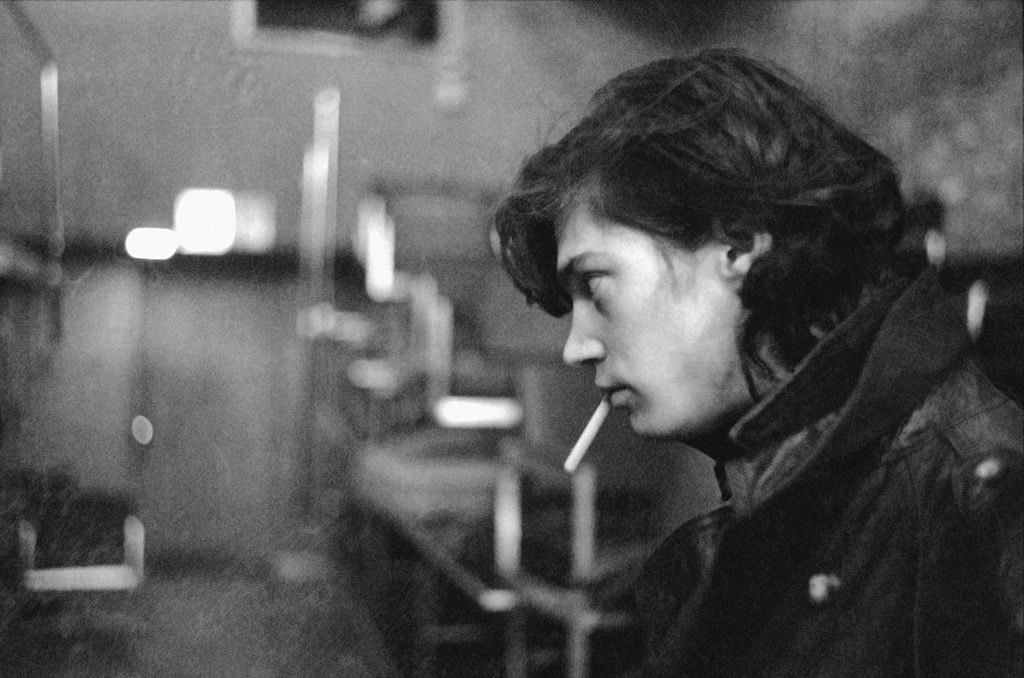

Robert Mapplethorpe, the subject of one of Crump’s films. Photo by Leee Black Childers/Redferns

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in rural Indiana, between Bloomington and Indianapolis. In the 1970s, they called it a “bedroom community,” but when my father moved us there it was chiefly farmland and corn fields. I earned extra money in the summers baling hay, which is the most physically taxing work I have ever encountered. My best friend was a sheepherder but his father was one of the scientists that created Darvon for Eli Lilly & Company, among the largest employers in the region. We used to get high smoking weed at five in the morning listening to the Stones before we took off on a daily and quite brisk five-mile run before high school classes started. We were track and field and cross country nerds.

Were you always interested in film?

My father was an accomplished photographer and my parents gave me my first camera, an Olympus OM-1 35mm, when I was 15. It gave me enormous inspiration and provided a kind of aesthetic jolt. I was already enthralled with the work of Richard Avedon and Irving Penn and I spent a lot of my time perusing my mother’s fashion magazines absorbing Penn’s and Avedon’s work, and many other greats from the late 1960s and early 1970s: Bob Richardson, Chris von Wangenheim, Helmut Newton, Antonio Lopez, Peter Beard.

I was a bag boy for a while at the local supermarket that had a newsstand where I spent all of my earnings purchasing fashion magazines, which looking back retrospectively, probably alarmed my parents. It was with Andy Warhol’s Interview, however, that I became an immediate devotee, reading it religiously, page-by-page, each month, learning about entertainers, filmmakers, musicians, painters, sculptors and all the creatives that populated New York City. “Art” was seeping in slowly, but really my main objective at around 15 years of age was to live in New York.

Did you ever make art?

Only photographs and a few photo-derived silk screened prints à la Warhol. Although I took many art history courses, I graduated college with a B.A. in economics and soon realized what I really wanted more than anything was to be near artists and the creative fields.

Richard Avedon, an early influence on Crump. Photo by Brownie Harris/Corbis via Getty Images

What were your earliest—as in childhood early—film efforts?

It would be decades before I would actually make a film, but I grew up with old Hollywood, films of the 1970s, and at an early age I became obsessed with certain directors. By that time I had already gone through an early John Ford and Howard Hawks phase because Westerns were what my family watched: Sam Peckinpah, Bob Rafelson, Peter Yates, John Huston, Arthur Penn. William Friedkin, Roman Polanski, Bernardo Bertolucci and many others from that generation.

My parents weren’t squeamish about the challenging films of that period and in fact they would frequently take us to R-rated films and they never censored our viewing. I remember going to the local premiere of Papillon with my dad where he was accosted by an angry woman accusing him of corrupting his children. Indiana was very homophobic then and, unfortunately still is, and local audiences took issue with the Querelle-esque homoerotic atmosphere and particularly the film’s only gay sex scene, but this did not phase my dad.

But I never had a hand-held 8mm or 16mm movie camera. In 2002, I was accepted into what was then called the Sundance Institute’s Independent Producers Conference, which was a crash course with seasoned filmmakers and industry giants in all aspects of filmmaking, from scriptwriting to production to casting and finance, and it was following that enlightening experience that I knew I was going to begin making films. By then, I was living in Chelsea in Manhattan and one day I determinedly went out and spent most of my savings, about $10,000, on equipment to make my first film, Black White + Gray: A Portrait of Sam Wagstaff and Robert Mapplethorpe (2007) which, fortunately for me, was executive produced by Maja Hoffmann and her husband, Stanley F. Buchthal.

What has been your most satisfying film project? Do you have a favorite? Or are they all like your children and you love them equally?

After Black White + Gray, it was several years later before I made another film, this time Troublemakers: The Story of Land Art, the first of several projects co-produced with Ronnie Sassoon, my partner. The Land art film might be the most satisfying because not only was it our first project working together, but it was an opportunity for Ronnie and me to indulge our fascination with some of the New York artists from the late 1960s and early 1970s who set out to make monumental, non-commodifiable works in the deserts of the American Southwest.

In that film, we interviewed the Vito Acconci, Virginia Dwan, Carl Andre, the late Land art photographer Gianfranco Gorgoni, and others from the milieu of Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt, Walter De Maria, and Michael Heizer. The highlight of that production was a helicopter shoot above Heizer’s Double Negative. That was perhaps the most exhilarating shoot I’ve ever been involved with. In some ways, it was quite harrowing as we ascended the densely clouded heavens above Vegas in a rare thunderstorm event that had me imploring the pilot to land. Fortunately, I was outnumbered by my four-man camera crew, one of whom vomited throughout the flight, to continue on to the remote mesa.

To your point, yes, I consider all of these films as children and they all presented unique challenges and memorable episodes while producing them. But I also consider the completion of any of my projects a kind of exorcism. Definitely, the most difficult unsavory experience of my career was making the Jordan Wolfson film, and not because you’re in it, Kenny.

Jordan Wolfson in Spit Earth: Who is Jordan Wolfson? Courtesy of Summitridge Pictures.

Explain the Jordan Wolfson film—a great film I happen to be in—and your experience with artist.

Was that your first film? I like to think I gave you your start. Spit Earth: Who is Jordan Wolfson? had to do with having begun tracking his work around 2013 and then meeting the artist and being utterly astounded by his outsized personality and his physical, one might even say menacing presence. He’s this amazing, seductive, entertaining, controversial, some have said incredibly sociopathic personality, and having met him in 2017 at his Red Hook studio, I was so impressed with how he presented his work. I wanted to know him better. He was so articulate and intelligible and very forceful, but he also struck me as a savant, even robotic. Turns out Jordan is the perfect foil to tell a lively story about the diseased condition of the hyper-speculative contemporary art market. Put a mirror up to him and what’s revealed is a kind of stereographic image of one artist’s struggle to co-exist with the art world and the endless compromises that must be made to survive. So that’s how that film got started.

Working with Jordan was quite challenging. It was difficult to establish a collaborative spirit with him because so much of the time Jordan was trying to control the narrative. I’ve done many diverse projects with nonliving creatives over decades. I would say that working with dead architects and dead artists is far less challenging. It’s much more challenging when you have a living subject like Jordan, who is incredibly manipulative, mercurial, controlling, and very insecure. Once the production was going, we had to block Jordan’s calls and texts. There was his obsessive need to try to steer the film in a certain direction, which was untenable to say the least.

Why did he protest? Did he ever stop?

I think the process of looking into that mirror and seeing his own reflection was just too much for Jordan. He didn’t like what he saw, though I made it clear from the beginning that this would be an honest portrayal, that I wasn’t interested in any kind of puff piece. Jordan was all on board with this, even emailing me a list of people I should interview who “hated” him.

I think Jordan over time was oblivious to how much he shared about himself. He reveals so much, and I think for him there is regret in that. I was always intrigued by the protests Jordan made and his beseeching fellow artists not to give into fear on Instagram and other social media. He says in the film that he can’t make his work if he gives into fear, but to me Jordan is one of the most fearful artists that I’ve ever met and this fact is underscored by his behavior towards me and Ronnie once the film was completed.

He was paranoid of what viewers would take away from the film, so he barraged us with threatening text messages for what seemed like a long time. Once he realized he couldn’t get his way, he disavowed his participation in the film one week before its release and then began reaching out to other interview participants asking them to withdraw statements they had made about him on camera.

Did you feel differently about him after project? Are you still in touch with him?

I’ve personally experienced firsthand Jordan literally physically accosting me, outside the Matthew Marks Gallery in L.A. after a Laura Owens opening, which, in a strange way, is consonant with his practice. We are no longer in contact with him. I don’t regret making the film as I think it’s a well-made and well-balanced portrait of a troubled artist, and if anything it has helped his career.

Marcel Breuer, at left in a dark suit, looks on with Jackie Kennedy during the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the Whitney’s Breuer building.

Your latest film is on Marcel Breuer. Why him?

I became interested in him the first time I visited his Whitney Museum of American Art in New York in the early 1980s. I’ve been fascinated with Breuer and his prolific output ever since, but in 2016 Ronnie and I were fortunate to acquire Breuer’s Stillman House II in Litchfield, Connecticut, which is what really got this project rolling. We began to meet other residents of Breuer-designed houses and that led to us to meet some of the children that grew up in these homes. The wild stories we collected of Breuer and his circle of friends and advocates in Litchfield struck me as right out of Frank Perry’s The Swimmer or Ang Lee’s The Ice Storm, both of which were also shot in Connecticut and covered the same period of time explored in our film. These were eccentric, decadent versions of the quintessential affluent American suburban families, but underneath the visage of Breuer’s exacting modernist architecture real lives were being torn apart. The narrative potential was too strong to resist.

One of the most profound realizations were the emotional costs of growing up in these residential properties and their underbelly of heartache and disfunction. Breuer’s binuclear designs for these houses, which provided for the physical segregation of the children from their parents, was literally divisive and probably emotionally destructive. This conceptual sleight baked into the architecture itself seemed to me to almost reject some of the utopian promises and optimism of modernism. It was a revelation—a sad one, but something that had never been considered before.

Ronnie Sassoon, Crump’s partner. (Photo by Stefanie Keenan/WireImage)

Your producing partner is Ronnie Sassoon, hair stylist Vidal Sassoon’s widow. What is your working relationship like?

Ronnie has been integral to all of the last four films, with a great deal of critical input, and we have a very copasetic working relationship. We occasionally have disagreements over pacing or sequence, but rarely do we have aesthetic differences. Ronnie typically styles the set ups, but we spend inordinate amounts of time together editing footage. We of course work with professional editors, but for months we painstakingly work over the rough cuts in intense editing sessions that for most films is five or six hours a day for two to three months before we hand it over.

The Breuer film will be released with a companion book and Ronnie was the primary editor of my texts, seven chapters worth. We trust and rely on each other’s critical opinion and I edit her writing as well. She, too, has a forthcoming book releasing this autumn entitled Selection, about her collection and aesthetic, that will be published by August Editions in November.

You were friendly with Zaha Hadid. Would you ever do a film on her?

The first time I met Zaha, you were hosting a dinner for her at the Delaunay in London where you admonished Nicholas Alvis Vega for freeloading! But I really got to know her through Ronnie, who considered Zaha her best friend when they were both living in London. I was fortunate to get to spend time with her in the last years of her life. We got on very well and on more than one occasion were seated next to each other at dinner parties engrossed in stimulating tête-à-têtes. A few years before she died we did consider producing a Zaha film. Now that she is gone, I think such a project would lack her unique presence, sarcastic wit, and humor.