On January 28, 2011, Egyptian multimedia artist Ahmed Basiony, 33, returned to Cairo’s Tahrir Square to protest. Just like millions of other Egyptians, he demanded the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak and an end to his 30 years of autocratic rule. Basiony, known for his work in new media technology, screamed and yelled, until he was beaten by riot police and was shot dead by snipers from the Egyptian Police Forces. He left behind a wife and two children, an artistic legacy and desire for change that still resonates in the Egyptian art scene.

Basiony’s life and work was displayed that year in the Egyptian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The installation showed footage of protests filmed by Basiony days before his death, alongside a video installation of his final performance at Cairo Opera House titled 30 Days Running in Place.

“I have a lot of hope if we stay like this,” he wrote on his Facebook page, two days before his death. “Riot police beat me a lot. Nevertheless, I will go down again tomorrow. If they want war, we want peace. I am just trying to regain some of my nation’s dignity.”

A video still from Ahmed Basiony’s multimedia live performance 30 Days Running in place (2010). Photo: Family of Ahmed Basiony.

During the summer of 2011, the Egyptian pavilion was deemed a sign of the growing acceptance of political art in the Arab world. But 11 years later, the same voices that rose against autocratic rule then continue to be silenced. State imposed censorship and self-censorship are widespread across the region, affecting the creation of art.

Moreover, a championing of Arab art by the wider art world, along with an interest in the complex geopolitics of the region, has also waned, as have auction results and prices. This has led many artists from the region to ask: Does there need to be a conflict for the art world to pay attention to us? Or are we just part of another geographic trend that has come and gone?

Lost Dreams

When revolution broke out across the Arab world in 2011, against dictators and their repressive policies, the art scene followed. Foreigner donors, curators, collectors and critics flocked to the region.

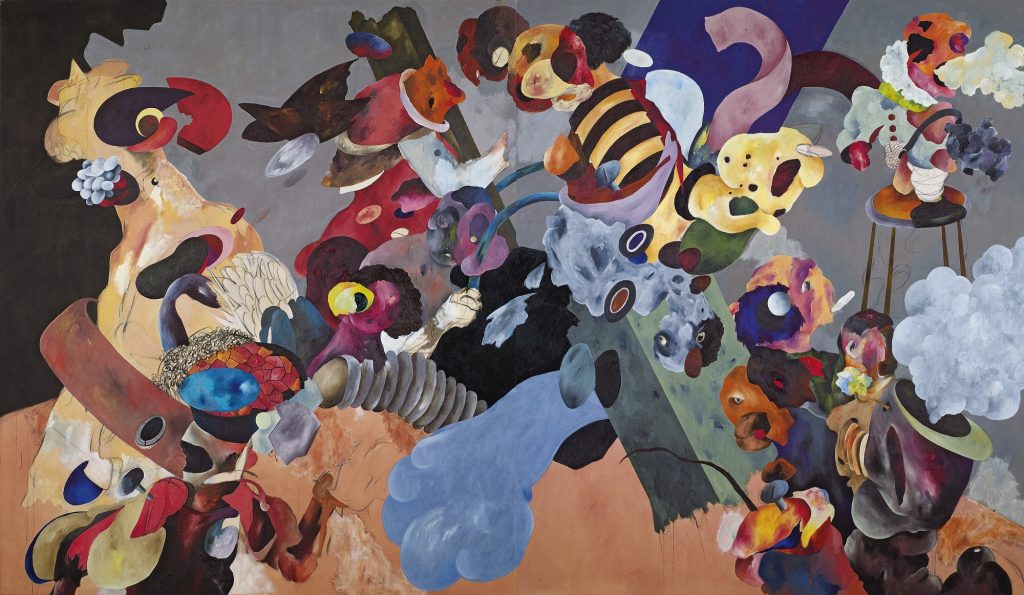

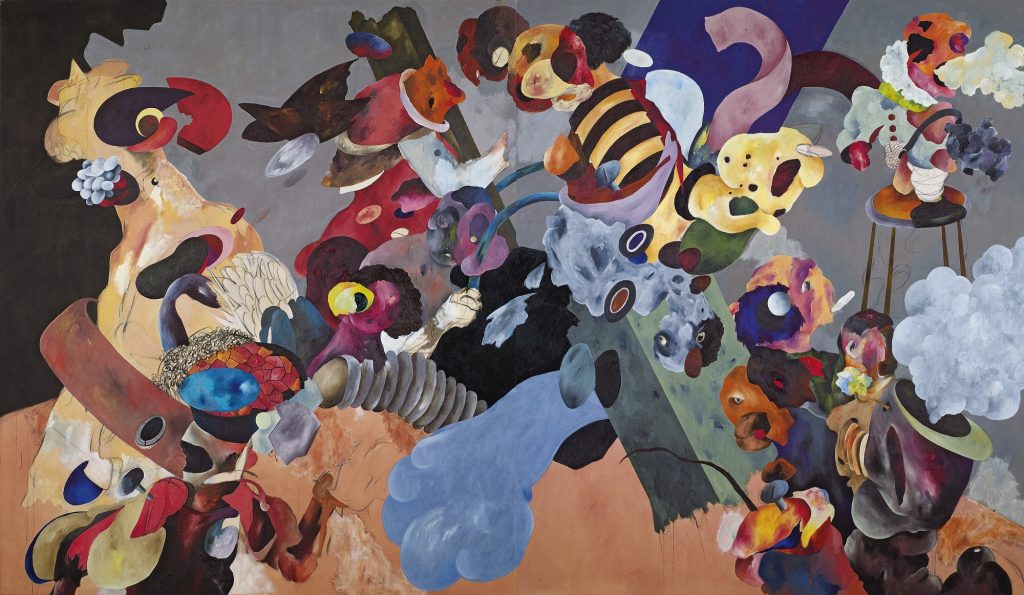

All eyes were on Arab artists at the 54th Venice Biennale in 2011. The Art World’s New Darlings was the title of a piece in the New York Times that year featuring stars from the Middle East, like Ahmed Alsoudani, an Iraqi Baghdad-born painter who fled to Syria during the first Gulf War before claiming asylum in the U.S.

A victim of the auctions, speculation, and hype of the moment, in 2011 Alsoudani’s Baghdad I (2008) sold for a record $1,127,472 at Christie’s London—but just a few years later, his prices drastically dipped. At a Christie’s London sale in 2015, a painting by the artist fetched only $87,232. Most recently, at a Sotheby’s sale in May 2020, one of his works on paper, You No Longer Have Hands (2007), sold for $2,772, just shy of its high estimate. Since then, the artist has had less prominence on the international scene.

Ahmed Alsoudani, Baghdad I (2008) sold for a record £713,250 ($1,127,472) at Christie’s London in 2011. His prices have dropped significantly since then. Photo: © Christie’s Images Limited 2022.

In many ways, Alsoudani was part of the Arab art “boom” that began around 2009. The region’s artists flourished, garnering international attention through an uptick in museum shows, auctions and gallery representation. At the 2011 Venice Biennale, “The Future of a Promise” was the largest-ever Pan-Arab show of contemporary art, with artists participating from Tunisia to Saudi Arabia.

That same year in London, Boris Johnson launched the first annual festival of contemporary Arab art and culture, the Shubbak Festival.

“All eyes turned to this region and what was being produced here and the money was showered on us,” said an Egyptian arts professional speaking on condition of anonymity, who stressed that from 2000–10, an independent arts scene in Cairo, Alexandria, and other cities flourished thanks to foreign money in the absence of state funding. “There was this seduction for our art—for art being produced during the revolution.”

However, there was a catch. The donors, the Egyptian arts professional continued, will support artists who are creating work around the themes of human rights, freedom of expression or women’s rights. “There’s always a political edge underneath the financial support; it is not just for the sake of art and art practices.”

Freedom was only briefly tasted in Egypt. After Mubarak stepped down, Mohamed Morsi, an Islamist with ties to the Muslim Brotherhood, briefly ruled Egypt (2012-2013). “Many were keeping a low profile, self-censoring, and hoping that the foreign donors would continue to fund them,” our source said.

When General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, Egypt’s current president, took office in 2014, the country’s fragile arts ecosystem, which for years had hung by a thread largely thanks to private donors, began to shut down.

“The government restricted what foreign donors could do in the country because they feared the money received was going towards social activism fomenting the country’s revolution—that was the paranoia of the government,” our source said. “When the money dwindled from the outside, most art spaces had to close or find other means to operate to survive.”

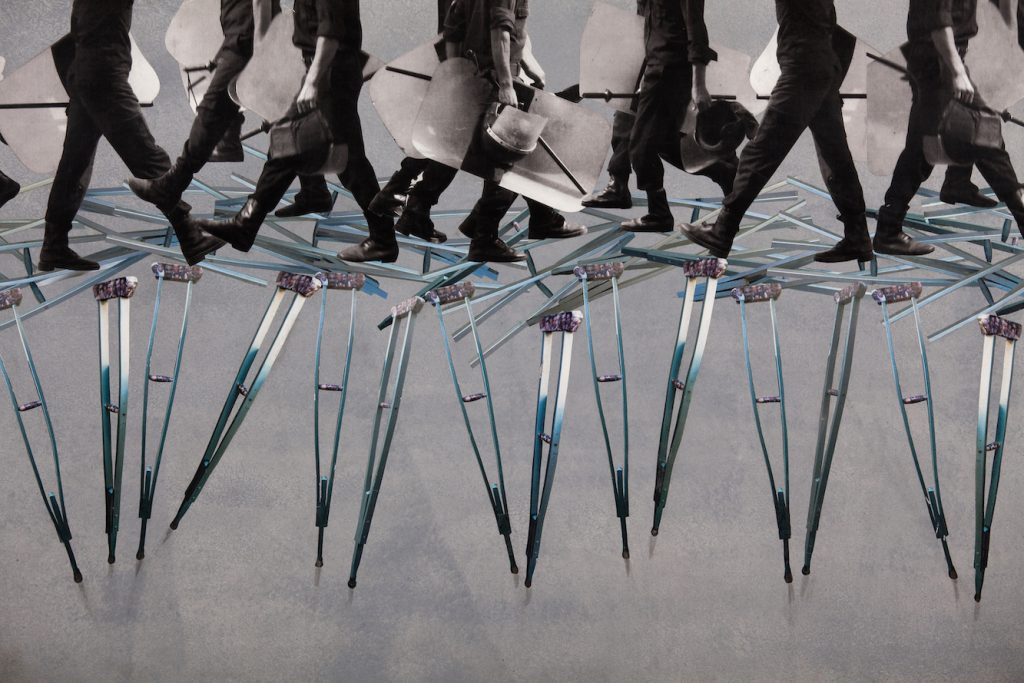

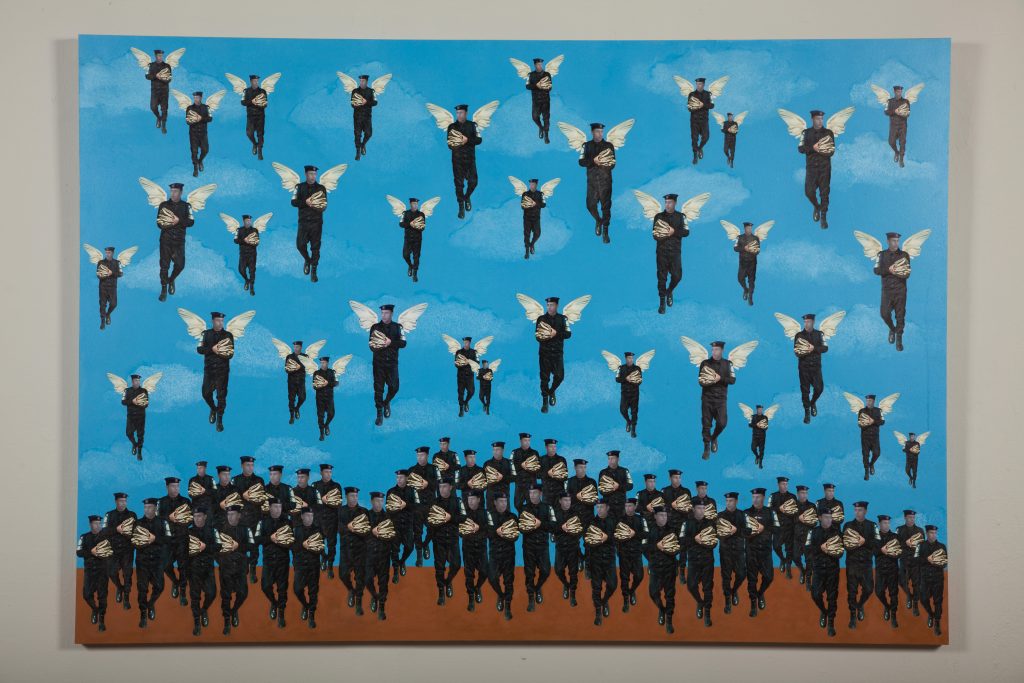

Huda Lutfi, Train of Badrashayn (2014, commemorating death of more than 30 soldiers during a train accident). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Egypt’s story parallels that of Syria, Palestine, Yemen and Tunisia. While Tunisia was once deemed the only success story of the 2011 Arab Spring uprisings, many now fear autocratic President Kais Saied is set to secure more power under a new constitution that will march the country towards one-man rule.

Since 2018, a second wave of protests known as Arab Spring 2.0 has swept the region. But this time, the demonstrations haven’t caught the international attention they first did. They have become familiar, cyclical, and almost expected—part of the media noise backdrop.

Distorted Perceptions

Amid the ongoing climate of fear and repression, artists and art professionals struggle to be seen as separate from the conflicts that engulf them.

“After the second intifada in 2007, the spotlight was on Palestine. Then the Arab Spring took place and all the funding and the spotlight went to Tunis, and then to Egypt, and then to Syria. And then the Gaza massacre happened in 2014, and the spotlight came back, and then back to Syria and the refugee crisis, etc,” Jerusalem-based artist Benji Boyadgian told Artnet News.

But what can get lost in this whirlwind of media attention is the legacy of such conflict, and the continuing emotional and psychological trauma. In August, three Iraqi artists—Sajjad Abbas, Raed Mutar, and Layth Kareem—pulled out from the Berlin Biennale to protest a work that included photographs of prisoners being tortured at the infamous U.S.-run Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

“There is a destructive cynicism in focusing on regions with conflict or socio-political changes—mediatized regions at certain moments,” Egyptian artist, musician and writer Hassan Khan told Artnet News, “that’s how spectacle works.”

Boyadgian said it is not just about artists portraying conflict, but about the way we approach image and conflict. He posed this question: “Is the work just reflecting the object of critique by reproducing it?”

Similar questions are being asked by Israeli artists in the context of allegations of antisemitism at Documenta 15. Tel Aviv curator Tamar Margalit told Deutschlandfunk Kultur radio that, for Israelis, “there is this implicit expectation that you have to deal with the situation here, with the conflict, and have a political point of view. And there is certainly a lot of exciting political art here. But that’s not the only type of art that should be on display.”

For independent curator and writer Alexandra Stock, based in Cairo since 2007, conflict is just one of the lenses through which art is seen and understood.

“Why is that? Is it because it is being filtered through a western lens and it must be put into a context where it needs to be justified?” she asked. “Art here has almost never had a chance to exist for its own sake. It almost always needs a reason to exist.”

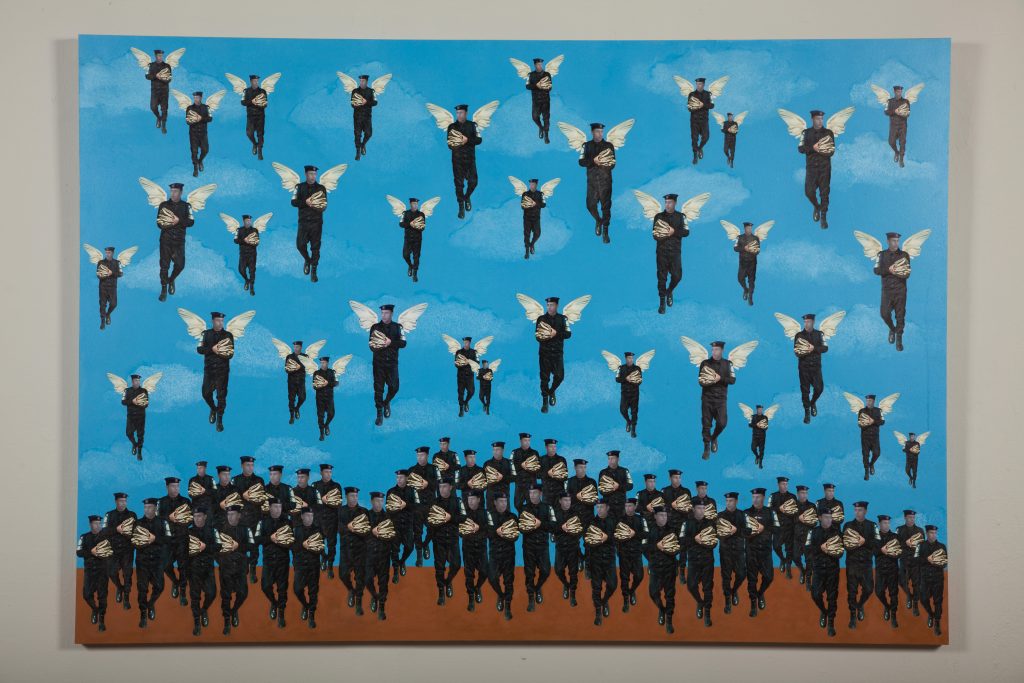

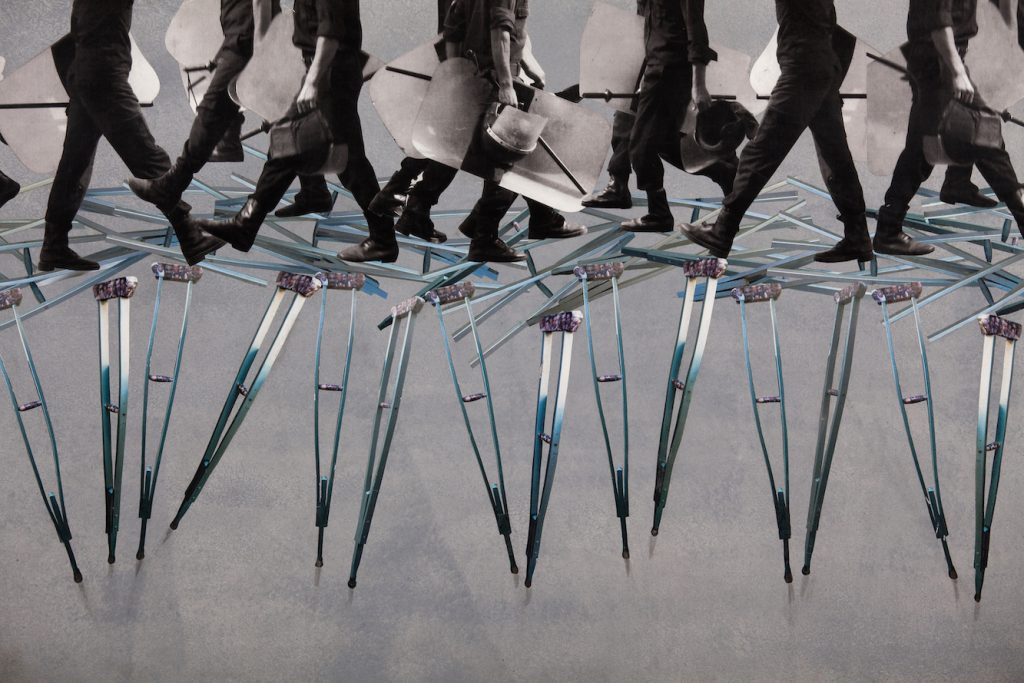

Huda Lutfi, Marching on Crutches (2014). Photo: courtesy of the artist.

Geographic Trend or Conflict-Obsessed?

So why does Arab contemporary art not sell like before?

Dealers around the region say it has to do with market speculation and the art world’s obsession with geographic territories. Others attribute it to a lack of quality art on the market and the paucity of collectors.

“Most collectors today have no interest in the aesthetic value of works of art—only its commercial value,” Saleh Barakat, a Lebanese dealer based in Beirut, told Artnet News. “Arab collectors now don’t have confidence in their own art; they have switched to buying American artists.”

Barakat added that “Middle Eastern art had its time. Now it’s Africa’s turn.”

Charles Pocock, cofounder of Meem Gallery in Dubai and an advisor to the Barjeel Art Foundation in Sharjah, sees less of a correlation in buying trends. “Extreme conflict always brings international attention to a region’s art movement and that’s a fact,” he said, “but I do not believe the tastes of collectors from the region are influenced by conflict.”

“Artists aren’t making enough work because there aren’t enough collectors to buy the work,” one collector told Artnet News, on the condition of anonymity.

Sales results at auction houses paint a mixed picture. For all of 2010, Christie’s Dubai sales brought in $29 million, up from $13 million in 2009. During that same time, two groundbreaking displays further pushed art from the region onto the global stage: British collector Charles Saatchi’s exhibition “Unveiled: New Art from the Middle East” and the opening of Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, Qatar.

In April 2011, revenues for Christie’s Dubai totaled $7.3 million, with 43 new auction records made for the region’s artists. Younger artists’ work accounted for $2.3 million of that total.

However, ongoing political turmoil in the Middle East, including heightened tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia, Dubai’s pre-Covid recession, Lebanon’s financial and political collapse, all threatened the regional art market.

Under former President Donald Trump, the U.S. reinstated economic sanctions against Iran, making it difficult for Iranian collectors—long some of the biggest buyers at auction—to participate in international sales. The Lebanese, another group of traditionally big buyers, remain strapped for cash.

In January 2020, Christie’s cancelled its Middle Eastern art auction in Dubai, citing a lack of top-quality works. The auction house has maintained one London sale of Middle Eastern art each October, but total sale results have dropped, now hovering around $2.5 million.

Emiratis at Christie’s in Dubai. Photo by Kaveh Kazemi/Getty Images.

Sotheby’s, which has maintained two sales per year for contemporary Arab, Iran and Turkish art, has also seen a drop in revenue on this work. Although the auction house maintains that “major works” from the region have gone into sales organized by other departments, Sotheby’s April 2019 sale for the category totaled just under $4 million and in March 2022 it brought in $2.3 million.

Today, as despair encompasses the region, Basiony’s earlier cry for dignity and freedom, like that of so many others, rings fainter and fainter.

“It is perverse, but this is what it is. Orientalism is not over,” Boyadgian said. “This is the evolution of Orientalism—the exoticism of conflict.”