Artnet News Pro

5 Artists Who Work Extensively With Robotics Offer Tips on How to Do It (and Reveal How Much It Costs)

The work can be expensive to make—but it doesn't have to be.

The work can be expensive to make—but it doesn't have to be.

Anna Sansom

The longstanding relationship between art and technology has evolved in the last few decades to the point where many artists today are making groundbreaking work using robots and artificial intelligence. Where the crossover field of art and robotics was once somewhat of a tech art niche, the capacity for artists to harness technology means that the field is expanding to a broader number of players.

Within the realm of robotic art, one of the early pioneers was Nam June Paik, who used radios and television monitors to create his Bakelite Robot (2002), a humanoid sculpture made from nine vintage Bakelite radios. Among other early proponents are Angela Bulloch, who began her ongoing “Drawing Machine” series in 1990, and Michael Landy, who developed moving sculptures described as “robotic saints” for an exhibition at London’s National Gallery in 2013.

Today, more artists are experimenting with bespoke technology to make installations and sculptures. Indeed, Anicka Yi’s current installation for the Hyundai Commission at Tate Modern, “In Love With The World,” involves machines based on ocean-life forms and mushrooms, which the artist calls “aerobes,” floating around the museum’s Turbine Hall.

We spoke to five artists using robots in their work to give us an idea of how it works, the costs involved, and their top tips for others hoping to experiment with technology.

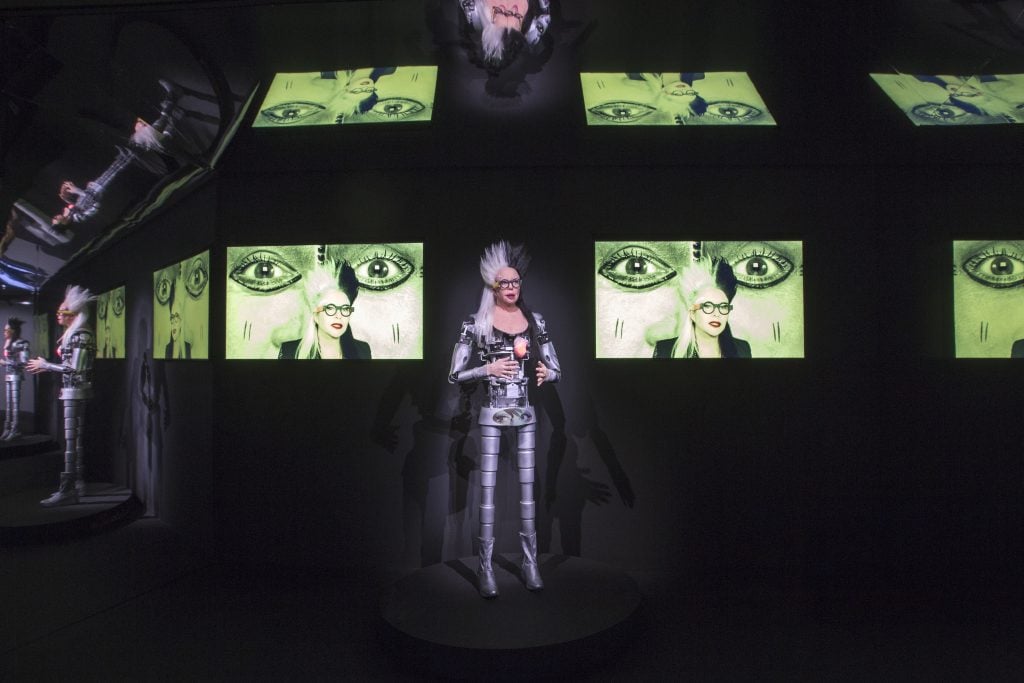

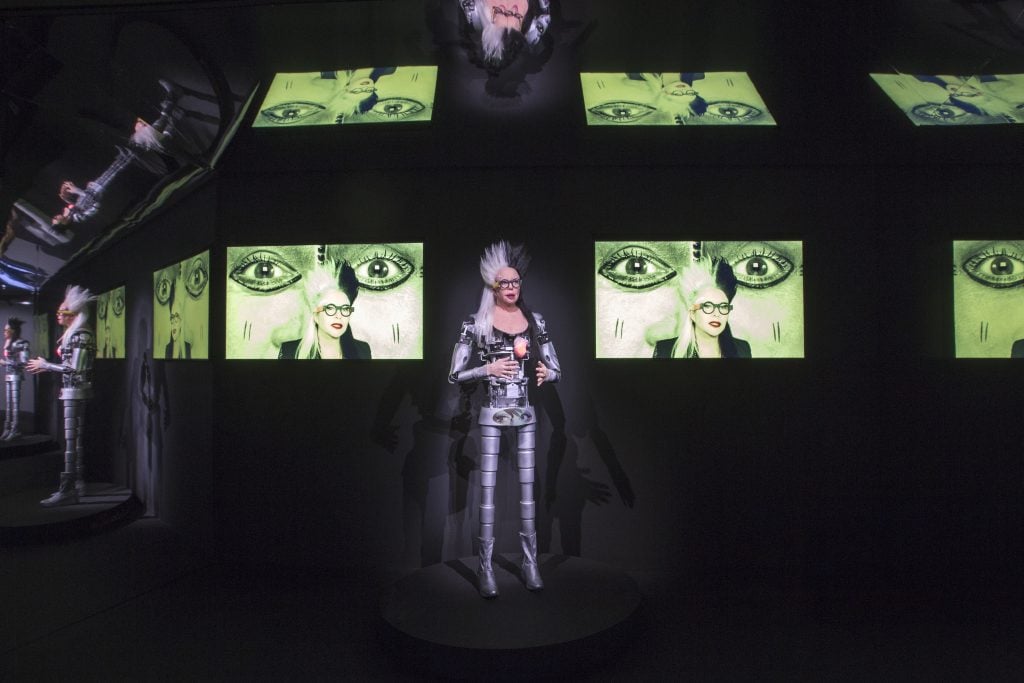

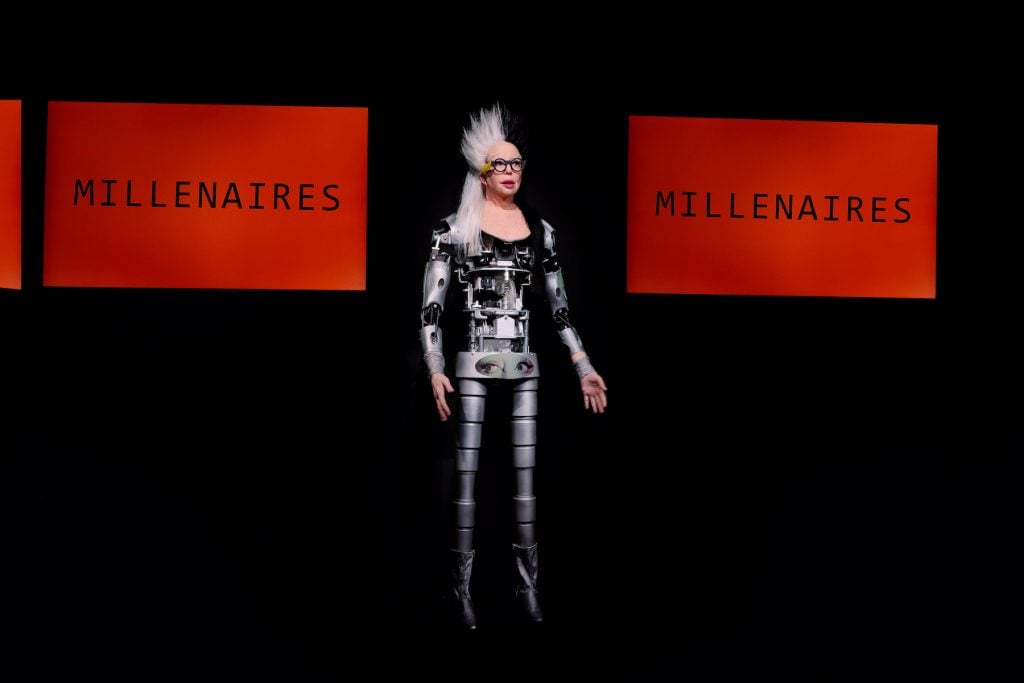

ORLAN, ORLANoïde (2018), installation in the “Artists & Robots” exhibition at the Grand Palais in Paris.

Who: The French multi-media artist ORLAN, famous for filming her “surgery-performances” in 1990–1993, has forged her career by making avant-garde works that interrogate the body. “I’ve always been interested in innovation and societal phenomena, and as soon as I heard about artificial intelligence, I looked into it, asking myself how I could say something important and in what way,” she said. “It was important for me to conceive a sculpture in my image, and that this moving, animated body could talk. To find the budget, I needed to find a well-known infrastructure to invite me to create an artwork.”

Referring to Luc Julia, author of “There is no such thing as Artificial Intelligence”, ORLAN added. “For me, artificial intelligence doesn’t exist, at least not yet; one could rather talk about ‘augmented intelligence’ or ‘auxiliary intelligence.’”

What: In 2018, ORLAN was commissioned by Laurence Bertrand Dorléac and Jérôme Neutres, curators of the exhibition “Artists & Robots” at the Grand Palais in Paris, to create ORLANoïde, a self-resembling robotic sculpture programmed to speak with her voice. “I recorded 22,000 words that we put into separate MP3 players,” ORLAN said about ORLANoïde, which spoke and interacted with video images from her performances.

To make ORLANoïde, ORLAN collaborated with the French fabrication company Animatronix and with Nicolas Gaudelet from Voxels Productions. Following the exhibition, ORLANoïde has been to Science Gallery Dublin, part of Trinity College Dublin, whose experts installed new features. “ORLANoïde is now capable of translating live everything I say into English. I could therefore take it with me as my translator whenever I go to give a conference,” ORLAN said. “I’d welcome other AI experts giving ORLANoïde further competences.”

Cost: ORLANoïde cost more than €140,000 ($158,000) to make. “There were people who worked [pro bono] as well as my interns and technicians at the Grand Palais,” ORLAN said.

Top Tip: “An artist shouldn’t make a robot just to make a robot and be on trend,” ORLAN said. “It’s about inventing something singular, not just researching the best technology, but developing a position and discourse on this technological phenomenon of society.”

Ai-Da. Image Courtesy Aiden Mellar.

Who: Aidan Meller is a gallery director based in Oxford who has worked with the estates of Camille Pissarro, Pablo Picasso and Marc Chagall. Branching out from the historical western canon, he created Ai-Da, a humanoid, robotic artist with artificial intelligence in 2019. Meller collaborated on the project with Engineered Arts in Cornwall as well as PhD students from Oxford, Birmingham and Leeds, bringing together an international team of more than 30 people.

What: Meller commissioned bespoke algorithms to enable Ai-Da to draw, paint, write, speak and see; Ai-Da can draw thanks to having cameras in her eyes and a robotic arm. Two years ago, Ai-Da had a solo show, “Unsecured Futures,” at the Barn Gallery at the University of Oxford. Other exhibitions include London’s Design Museum earlier this year, where Ai-Da made a self-portrait using mirrors. The Design Museum hailed her as “the world’s first convincing humanoid robot capable of creating artworks”.

Cost: Meller said he was unable to provide information on the cost of the project due to non-disclosure agreements made with the companies that he collaborated with.

Top Tip: Meller encourages more artists to get involved in the “remarkable” area of artificial intelligence. For a cross-disciplinary project to be successful, “communication is key,” he said. Meller is emphatic about the need to consider the impact of technology. “Philosophical and ethical questions are so important,” he insisted. “As Ai-Da was detained when entering Egypt recently, we know technology is feared. It’s very wise to question it so that we have a safer world.”

Sougwen Chung, Exquisite Corpus (2019).

Who: Sougwen Chung is a 36-year-old Chinese-born, Canadian-raised artist based in New York. A former research fellow at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she began programming and building robots named D.O.U.G. (Drawing Operations Unit Generation) in 2014. Together they have produced drawings and paintings in performances with the robots mimicking her gestures. In 2016, she won the Excellence Award at the Japan Media Arts Festival for her work. Last year, she live-streamed a robot collaboration to Sørlandets Kunstmuseum in Norway, where it was exhibited as a video installation. And in October, she presented abstract paintings, sculpture, video and performance made in collaboration with robots during her exhibition “Entangled Origins” with Gillian Jason Gallery at Asia House in London. “Developing new approaches to embodiment, memory and improvisation is what excites me about technology,” she said.

What: Chung works with biosensors from Open BCI and Muse, and VR headsets such as Oculus and Vive, among other technologies. “We’re developing bio-inspired robots that can embody human traits, focus on collaboration, co-creation and care, and steward natural ecosystems with regenerative power sources,” she said. Chung was invited by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation in Athens to perform the first “phase” of her multi-robotic system linking to “bio feedback” and satellite data at the Greek National Opera last August. Chung is also exploring links between machines and ecology in her project “Floral Rearing Agricultural Network.”

Cost: Chung writes bespoke software using a variety of robotic arms from Ufactory (which cost $10,999.00–$11,999.00) and Kuka.

Top Tip: “Start with a ritual, task or practice that means something to you like mark-making, dance, sculpting, or singing and try to find ways to invigorate that existing practice with robotic development,” Chung said. “Most of these technologies are designed for automated tasks but really beautiful and strange things can happen when you approach it like a human-machine duet. You need to let go of control and trust the process.” However, the artist warned: “Robots don’t always do as they’re told.”

Patrick Tresset, Human Study #1 (2011).

Who: Patrick Tresset is a Brussels-based artist with an MPhil in Arts and Computational Technologies from Goldsmiths College in London. He participated in the group exhibition “Artists & Robots” at the Grand Palais in Paris in 2018, and has shown his work at the Haus Der Kunst in Munich and Mori Museum in Tokyo, among other venues. He integrated robots into his practice in 2010 after becoming fascinated with new technologies. Tresset creates robots for his performative installations where robots take on the role of actors. For instance, in Human Study #1 (2011), based on a life-drawing class, several robots have sheets of paper on their desks and are tasked with sketching the human being sitting in front of them. The robots produce the drawings live, prompted by an assistant who twists their arm so they start drawing.

What: Tresset buys components, such as motors, from the Korean company Robotis, which enables him to create bespoke robots. “The most complicated thing is writing the software, which I develop myself,” he said.

Cost: Components from Robotis cost €50–€600 ($56–$678). Costs to make a large installation with 20 robots can reach €20,000 ($22,600).

Top Tip: “Be patient, focused and don’t reinvent the wheel,” Tresset said. “Using robots takes a lot of time, far more than just developing software.” Technical complications can arise, so testing and preparation is required. “The first time that I exhibited robots in an art fair, they didn’t work for the private view,” Tresset recalled. However, the advantage is clear: “Robots are always well received by audiences worldwide.”

So Kanno, Lasermice Dyad installation (2021). Art Laboratory Berlin. Photo by Masashi Kuroha.

Who: Born in Japan in 1984, So Kanno has been based in Berlin since 2013. He began making digital art in the late 2000s and started developing robots six years ago when he recognized the potential for creative expression using sensors, motors, displays and speakers. After initially making interactive pieces, his interest shifted to generative and autonomous systems. His latest pieces are based on a “swarm robotics system” inspired by the synchronous behavior of insects like fireflies. At the group exhibition “Swarms, Robots and Post-nature” at Art Laboratory Berlin this year, he presented the installation Lasermice Dyad (2021), involving several dozen small furry robotic creatures powered by electromagnets whose movements were illuminated by laser lights.

What: Kanno designed the robots himself after consulting the open-source platform Arduino and used Seeed Studio to produce the printed circuit boards (PCBs). “I would love to collaborate with companies that produce social robots or toy robots,” he said. “Creating a mechanism such as an algorithm, and controlling its behavior by adjusting its parameters, is a unique experience.”

Cost: The material cost of the 130 original boards produced for Lasermice Dyad was around $7,000. The total material cost, including materials such as motors, lasers and printed plastic, was about $22,700, prior to developing costs.

Top Tip: Buy more components than necessary in case some of them stop working and cannot be replaced. “Maintenance is a challenge and it’s often difficult to get the same parts a few years later,” Kanno advised.