The Appraisal

The Market for Marc Chagall Has Proven Surprisingly Resilient in Times of Economic Turbulence. Will the Trend Continue?

We took to artnet's price database to investigate.

We took to artnet's price database to investigate.

Naomi Rea

Earlier this month, Christie’s held a special auction of work by Marc Chagall as the prelude to its 20th and 21st century evening sales in London and Paris. The trove of fresh-to-market works consigned directly from the artist’s estate surpassed expectations, bringing in £9.7 million ($11.9 million) and exceeding its pre-sale high estimate of £6.5 million ($7.9 million). There was competition for all 20 lots, with many doubling expectations.

Some attributed the heightened interest to the predicted recession: At moments of uncertainty, when art is seen as a hedge against inflation, buyers look to park their cash in established names. Though Chagall rarely generates headline-worthy fireworks at auction, the prolific Russian-French painter is among the more frequently traded and is commonly cited as a safe investment alongside the likes of Picasso, Monet, Basquiat, and Warhol.

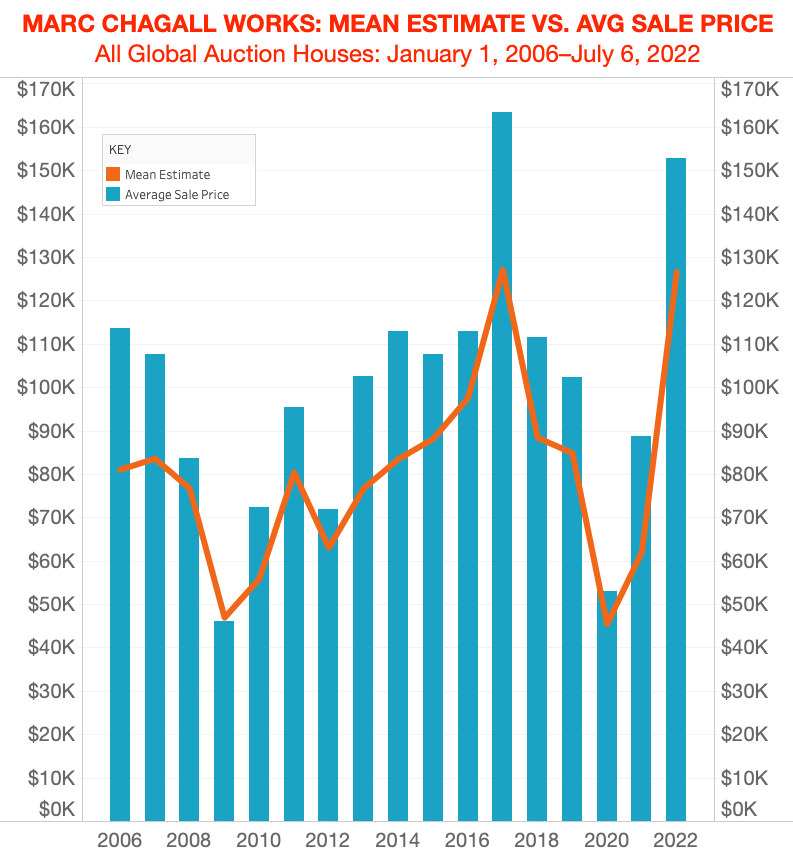

But exactly how impervious is Chagall to wider market volatility? We took to Artnet’s price database to investigate.

Auction Record: $28.5 million, achieved at Sotheby’s New York in November 2017

Chagall’s Performance in 2021

Lots sold: 887

Bought in: 260

Sell-through rate: 77.3 percent

Average sale price: $88,803

Mean estimate: $62,119

Total sales: $78.8 million

Top painting price: $6.2 million

Lowest painting price: $111,633

Lowest overall price: $88 for a lithograph of an image from Chagall’s “Bible Series”

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

Marc Chagall in August, 1934, in front of “Solitude” (1933). Photo by Roger Viollet via Getty Images.

While the above-par results for Christie’s Chagall sale could be explained by the size, color, condition, and pristine provenance of the works on offer, it’s hard to ignore the role played by the broader economic climate.

The market for Chagall is huge, global, and has proven relatively impervious to crisis in the past. Even when certain regions have pulled back, others have been waiting in the wings to replace them. To wit: Japanese buyers were supplanted by Russians in the 1990s, who have in turn been replaced by buyers in the Asia Pacific region. Meanwhile, when prices take a dip, they swiftly recover, suggesting that those looking to the art market to diversify their assets can still count on Chagall as a safe bet.

That said, a slowdown in buying from the Asia Pacific region, which has fueled the wider art market growth since the dawn of the pandemic and currently lifts up the higher end of the Chagall market, is beginning to make itself felt. What this will mean for Chagall, and for insiders’ efforts to encourage that pool of buyers to collect the artist in-depth, remains to be seen.