Artnet News Pro

The Appraisal: Why Does the Market for American Icon Robert Rauschenberg Lag So Far Behind His Contemporaries?

We dived into Artnet's Price database to see what it could tell us about the artist's market.

We dived into Artnet's Price database to see what it could tell us about the artist's market.

Naomi Rea

Last week, the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation announced that it would tackle a mammoth task over the next two decades: publishing a catalogue raisonné of the American artist’s paintings and sculptures. The first of the planned 10 volumes will be available in 2025.

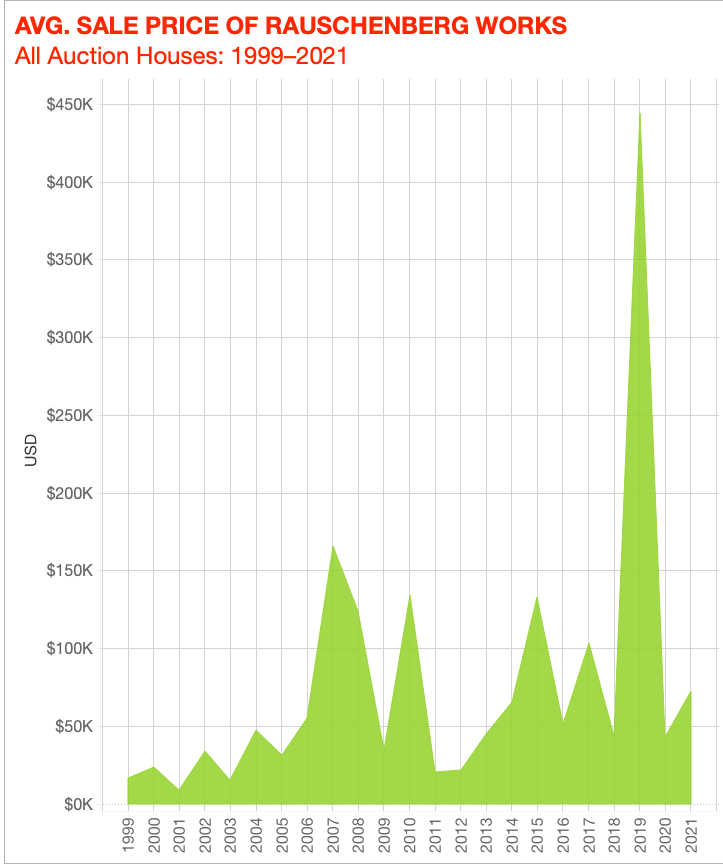

The foundation intends to make the catalogue available for free online, removing the challenge of acquiring a bulky and expensive encyclopedia for those interested in the artist. Could the announcement, which follows a new auction record for set in 2019, signal new life for Rauschenberg’s long-dormant market? We dipped into Artnet’s Price Database to find out.

Auction record: $88.8 million at Christie’s New York in May 2019

Rauschenberg’s Performance in 2021

Lots sold: 307

Bought in: 73

Sell-through rate: 80 percent

Average sale price: $72,443

Mean estimate: $45,007

Total sales: $22.2 million

Top painting price: $11 million

Lowest painting price: $2,300

Lowest overall price: $223, for a signed photographic etching from 1977

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

The 2019 sale was something of a watershed moment for Rauschenberg’s market, and saw him overtake the $36 million record for his contemporary Jasper Johns (another artist whose auction track record has suffered from a lack of supply). Nevertheless, the late artist’s prices have yet to reach the heights—or consistency—of peers such as Roy Lichtenstein (whose record stands at $95.4 million) or Andy Warhol ($105.4 million). And how long it will take for another top-tier example to appear on the market is anyone’s guess.

One thing is clear: other areas of Rauschenberg’s oeuvre have plenty of room to grow. The powerhouse gallerists working with the artist’s estate—Thaddaeus Ropac in Europe, Pace in the U.S., and Luisa Strina in Latin America—could help that matter along in the coming years (Ropac recently toured a group of grayscale metal paintings from 1991 while Pace is pushing the artist’s late-career return to painting). So could the forthcoming 10-volume catalogue raisonné, although the fact that it will not extend to drawings, prints, or other works on paper indicates that the focus of the moment may be elsewhere.

The later works may also simply need more time to appreciate. Consider the market for Picasso, whose late work—executed quickly and in high volume—was for a long time less desirable. To change that, it took a few key exhibitions and a new audience of high-end contemporary art collectors who could more easily draw parallels between the late work and the de Kooning and Basquiats already in their collections. Perhaps Rauschenberg’s late-career obsession with media and technology could find new takers in new buyers entering the market today.