The Back Room

The Back Room: Store of Value

This week: an art-market logistics mystery, big trouble at big auction houses and museums, extra-sunny buyer psychology, and much more.

This week: an art-market logistics mystery, big trouble at big auction houses and museums, extra-sunny buyer psychology, and much more.

Artnet News

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy.

This week in the Back Room: an art-market logistics mystery, big trouble at big auction houses and museums, extra-sunny buyer psychology, and much more—all in a 6-minute read (1,764 words).

__________________________________________________________________________

Barbara Kruger’s I Shop Therefore I Am at the Hirshhorn Museum. (Photo by Robert Alexander/Getty Images)

Every art pro is familiar with stories of deadbeat collectors refusing to pay for works they’ve committed to buy. But a weirder wave of unfinished transactions has been sweeping the industry lately: works paid for promptly but not picked up for months or, sometimes, even years.

Sound unreal? Our colleague Katya Kazakina had the receipts (literally, in some cases) in last week’s Art Detective. A few examples she unearthed included…

“I first interpreted this trend as a sign of a slowdown in the art market, the froth coming off—or maybe the low tide that exposes all the broken shells and mollusk skeletons on the now-visible ocean floor,” Katya wrote. But her sleuthing revealed that the phenomenon has multiple and varied origins outside any particular moment in the business cycle.

Three main causes emerged from her reporting, starting with…

Within the art world, buying more work than you can display is a badge of honor that’s also regularly (and paradoxically) labeled an addiction. Sometimes, the designation is more than just a euphemism.

Allen H. Weg, executive director of the obsessive-compulsive-disorder treatment center Stress and Anxiety Services of New Jersey, confirmed that any behavior can be addictive if it provides a powerful enough emotional experience—including buying art.

This is especially true if the behavior leads to an experience of elation, victory, or control. All three can (and do) manifest frequently in an acquisitions game centered on buying beautiful objects, identifying underappreciated value, and/or beating rivals to the trophy.

Weg even role-played the obsessive-compulsive mentality that could be at play for collectors who buy but wait ages to pick up: “It’s mine. I have control over it. I don’t necessarily need it to be this place or that place. I just know it’s mine wherever it is.”

Whether it qualifies as an addiction or not, buying at scale can cause rampant collectors to genuinely lose track of their own activity, leaving works unclaimed for extended periods even after they’re free and clear to be delivered.

Although high net worth individuals can usually buy whatever they want, whenever they want, they are also on near-perpetual alert for any additional value they can extract from the timing or structure of their transactions. This principle extends to art purchases.

Maybe waiting to ship a paid-for artwork carries tax advantages, particularly if the buyer shifts around other assets beforehand. Maybe a collector can’t (or won’t) accommodate a major work without either making pricey renovations to its intended home first, or paying hefty expenses for a specialty install (think: having to remove windows and crane an oversized painting into a high rise).

No matter what the reason, substantially more cash might need to be spun out of other assets before collecting an artwork is financially defensible to buyers. As attorney Thomas Danziger said, “Many of the richest people in the world are not liquid.”

Other times, however, this odd trend really does just boil down to frugality, if not outright stinginess.

Francisco Correa Cordero, owner and director of Lubov gallery in New York, said he wasn’t thrilled when China’s Xiao Museum left behind a group of eight purchased paintings for seven months. Still, he understood when he learned that the museum’s founder had gone on a shopping spree in New York and was waiting to consolidate all their artworks into one massive shipment.

Whether or not there’s a semi-defensible reason, saddling galleries or nonprofits (especially smaller ones) with already-sold art for extended stretches can cause real problems. Few have enough square footage to act as free storage units.

Yet that’s what buyers who delay shipping transform galleries into—often because it means they don’t have to pay for storage themselves in the interim.

__________________________________________________________________________

The ultimate irony of long-postponed art pickups is that understanding buyers’ reasoning changes nothing about artists and dealers’ options for action. Aggressive follow-up, let alone doing something as extreme as charging a client for storage, risks damaging a potentially lucrative relationship forever. Even major auction houses have been known to absorb long-term storage fees for big buyers.

Ultimately, for most sellers it’s still better to eat some extra costs than, as Castator said, to “bite the hand that feeds you.” And buyers know it, too.

____________________________________________________________________________

This week’s Wet Paint was still being mixed at delivery time for this newsletter, so here’s what else made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Art Fairs

Auction Houses

Galleries

Institutions

Obituaries and Legal News

____________________________________________________________________________

“I feel that artists have a choice—do you want to be in the Metropolitan [Museum of Art]? Or do you want to produce for a beach house? Doig to me seems to fall into the category of ‘he’s going to the Metropolitan.’”

—Jean-Paul Engelen, Phillips’s president in the Americas, lauding Peter Doig’s perceived goals while splitting the art market into a stridently old-school binary. (Artnet News Pro)

____________________________________________________________________________

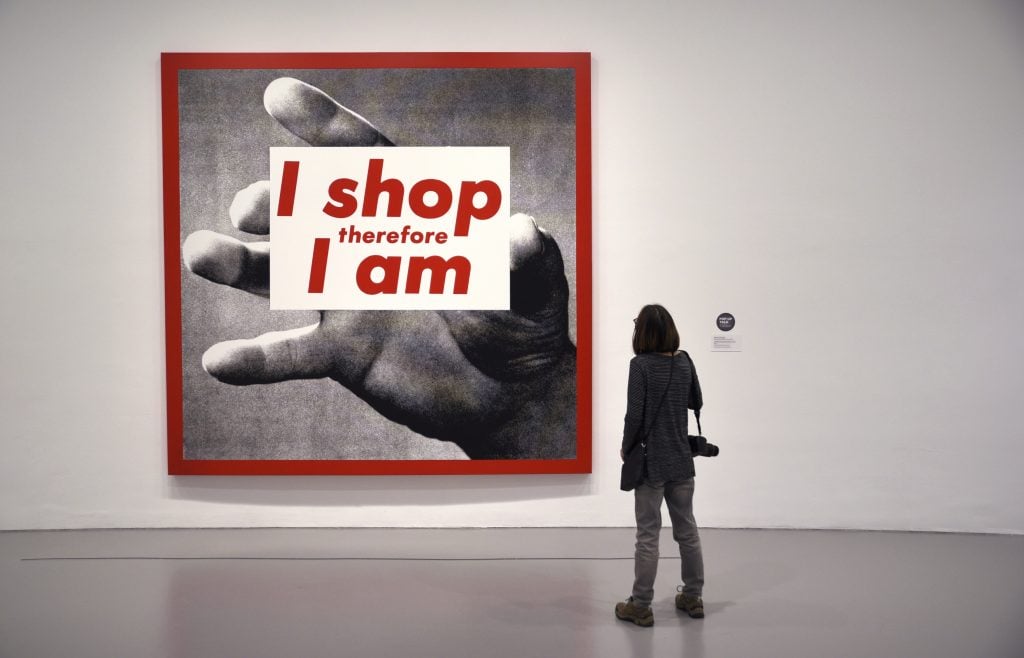

© Arts Ecoomics 2023, courtesy of Art Basel and UBS.

This week, Art Basel and UBS released the 2023 edition of Clare McAndrew’s annual quantitative report on the state of the industry. The headline is that global art sales were estimated to have ticked up to $67.8 billion in 2022, an increase of 3 percent year over year. But given the importance of sentiment to this eternally subjective trade, I’m most interested in the data from the report’s August 2022 survey of more than 2,700 high net worth art buyers across 11 regional markets.

The main takeaway? Even after eight rough months for the investor class, most wealthy people in the sample still felt awfully good about the art market’s prospects in 2023…

Eight months later, there’s no telling how many respondents still feel sunny about the art market’s near future. But since booms and panics alike are powered by beliefs more than by facts, this global wave of optimism helps explain one important reason that art sales have stayed so resilient amid so much other bad news.

—Tim Schneider

____________________________________________________________________________