Where is Jadé? Where is Anna? Where is Christina?

The familiar artist names that have regularly set off fireworks at recent high-stakes contemporary-art auctions are conspicuously missing from the lineup of London sales that are scheduled to kick off February 28. Their absence is all the more intriguing given that London’s auctions are the first public market test of the year, offering an important snapshot of the trends that are crystalizing as the season progresses to Hong Kong and New York.

One thing is clear: There’s a noticeable drop in the offerings of Black portraiture, bro-primitivism, and Spanish New Wave at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips. (Where are you, Otis, Jordy, and Rafa?)

Sotheby’s will offer the week’s only Nicolas Party painting, and Christie’s will present the sole canvas by Amoako Boafo—two artists whose works used to be ubiquitous. There’s not a trace of Matthew Wong, whose $48.5 million auction total in 2021 was halved last year.

Tastes change fast in the investment-driven art market. One of the first places to reflect a shift is the speculative ultra-contemporary segment, where prices for some artists were recently moving up-up-up with lightning speed. The sector’s auction sales grew 500 percent in five years, peaking at $741.4 million in 2021, when they surpassed the Old Masters, according to the Artnet Price Database. Now, ultra-contemporary is on the downswing. Last year the broader segment declined by 10 percent, to $668.2 million.

And because the feeding frenzy for many of these market darlings has subsided, speculators have begun testing new-to-the-scene artists. Auction houses are only too eager to offer the stage. Welcome to the Flip Class of 2023.

“There’s a voracious and enduring appetite among collectors for the new,” said David Galperin, Sotheby’s head of contemporary art for the Americas and co-head of marquee sales. “They are constantly seeking out new names. The auctions have become a place where a lot of collectors are introduced to new artists for the first time, and we tailor our sales meticulously to try to really paint a picture of what are the most interesting works being made today.”

Mohammed Sami, Family Issues I (2019). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Aptly titled “The Now,” Sotheby’s evening sale will begin with Mohammed Sami, an auction newbie whose 2019 painting of a carpeted room is estimated at £50,000 to £70,000. Born in Iraq, the London-based Sami is gaining curatorial attention, with a solo show up now at the Camden Arts Centre in the U.K. capital. His New York debut at Luhring Augustine gallery will feature paintings currently included in the 58th Carnegie International survey.

“Impossible to get primary,” an art advisor told me this week about Sami’s new works. It’s a perfect scenario to stage a multi-phone bidding war and set the mood for the evening auction.

In the same vein, Christie’s will start its 20th/21st Century evening sale with Michaela Yearwood-Dan, a young Londoner of Caribbean heritage, whose large and lush floral tableau is estimated at £40,000 to £60,000. Her prices surged to $388,798 at Phillips in December. A recent addition to Marianne Boesky Gallery, she has a show coming up in April in New York.

Phillips positioned Belgian artist Ben Sledsens as its opening act on March 2. Looking stylistically like a cross between Party and Scott Kahn, the painting Wanderer With Dog is estimated at £80,000 to £120,000.

The new crop of artists represents a change of guard from the earlier, pandemic-era cohort; their lower prices and greater resale upside is just what the flippers crave.

“There’s a huge pack of speculators,” said an auction executive. “It’s all pump and dump. And then they are on to the next thing. And auction houses just reflect what artists are being actively sought-after.”

Emerging-art speculators typically don’t buy half-a-million-dollar artworks. Instead they look for things under $50,000 and then create hype.

“They’d resell this work for $150,000 and it would be considered a great result,” said an auction specialist. “Then somehow $350,000 became the new $150,000, and then $600,000 became the new $350,000. It’s just like a product of this frenzied environment for young, contemporary.”

Christina Quarles, The Night That Fell Upon Us (Up On Us) (2019). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

It’s a lucrative but risky game. Avery Singer’s art reached its high total of $21.5 million at auction in 2021—and then dropped 28 percent in 2022. Christina Quarles peaked at $10.7 million in 2022, with an auction record of $4.5 million for Night Fell Upon Us (Up On Us), sold by collector Howard Rachofsky in May. Since then, not a single price has come even close.

“Yes, there haven’t been any paintings that have matched the price that we were able to achieve,” Galperin acknowledged of the Quarles market. “But I would also say that there haven’t been any paintings that have come up that matched the quality of this work.”

Ironically, the higher the auction results, the less attractive artists become to speculators. Their markets may remain robust (auction houses would kill to get an A+ Quarles or Jadé Fadojutimi), but trading volumes typically decline when primary prices catch up to secondary values and arbitrage goes away.

A new painting by Anna Weyant and Fadojutimi at Gagosian would set you back $500,000 or more. Hauser & Wirth was asking as much as $1.2 million for large-scale Quarles canvases in her New York exhibition last year, even as most of her older works were fetching $600,000 to $800,000 at auction.

“There are a lot of people who want a painting at $100,000,” an auction expert said. “There are a lot fewer who can pay $1 million. Instead of 20 bidders you get one or two.”

Meanwhile, new paintings by these artists are still too fresh to be resold. (Stringent non-resale agreements don’t help either.)

“You don’t wanna get blacklisted,” the auction executive said. “Especially since they put the prices at around the level that they were selling secondary. Where is the real upside? Why ruin your relationship with the gallery?”

Other speculative bubbles are getting deflated because of the overproduction by artists and taste changes among collectors.

The frenzy over Black figuration, for example, has subsided dramatically, advisors and auction specialists said. Auction houses are putting brakes on what they take. For example, there’s suddenly a lot less work by Isshaq Ismail, whose seemingly endless supply of heads flooded the market in the past year, selling for as much as $367,541 a pop last March.

Michaela Yearwood-Dan, Love me nots (2021). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

Bro-primitivism is another area of contraction. There’s just one painting by Robert Nava going under the hammer in London, at Christie’s evening sale. Auction houses are saying no to countless works by Jordy Kerwick, a stark reversal from October when his painting fetched $242,967 at Phillips in London. Ditto Susumu Kamijo, a Japanese artist whose poodle paintings have sold for as much as $274,724 since his auction debut in 2020, according to Artnet Price Database.

“People don’t have the confidence that they’ll make more than they paid,” the auction specialist said.

When the Zombie Formalism bubble burst, collectors watched how their investments plummeted at auction. The houses learned their lesson and came up with a new strategy.

“When the results start going down, we get really selective,” an executive said. “I don’t want it in my evening sale, I’ll put it in the day sale and off-season sale. So these things just get downgraded or they disappear.”

Others see this as a natural market evolution, from gluttony to refinement.

“The highest-quality artists rise to the top, and the public market starts to reflect that,” Galperin said. “You have extraordinary artists like Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, who has an incredible show at the Tate right now, or Njideka Akunyili Crosby, who’s going to open with Zwirner next year. These are artists who are making Black portraiture and who are in extraordinary demand.”

But supply of top-quality work is always tight. Which is why auction houses are constantly on the lookout for new names whose work is related but less expensive and easier to get.

“You’ll get somebody who’s similar, an artist who’s like the B-version or Johnny-come-lately,” the auction executive said. “You see this in music, too.”

Ben Sledsens, Wanderer With Dog (2017-18). Courtesy of Phillips.

That’s what Sledsens (estimated at £80,000 to £120,000) may be to Nicholas Party (estimated at £900,000 to £1.3 million); and Angela Heisch’s Egg White Blue (estimated at £20,000 to £30,000) to Loie Hollowell’s Split Orbs in purple, ochre, and… (estimated at £400,000 to £600,000) at Phillips.

“If you can’t get a Marlene Dumas, you can get Claire Tabouret,” an advisor said about two female artists, one generation apart.

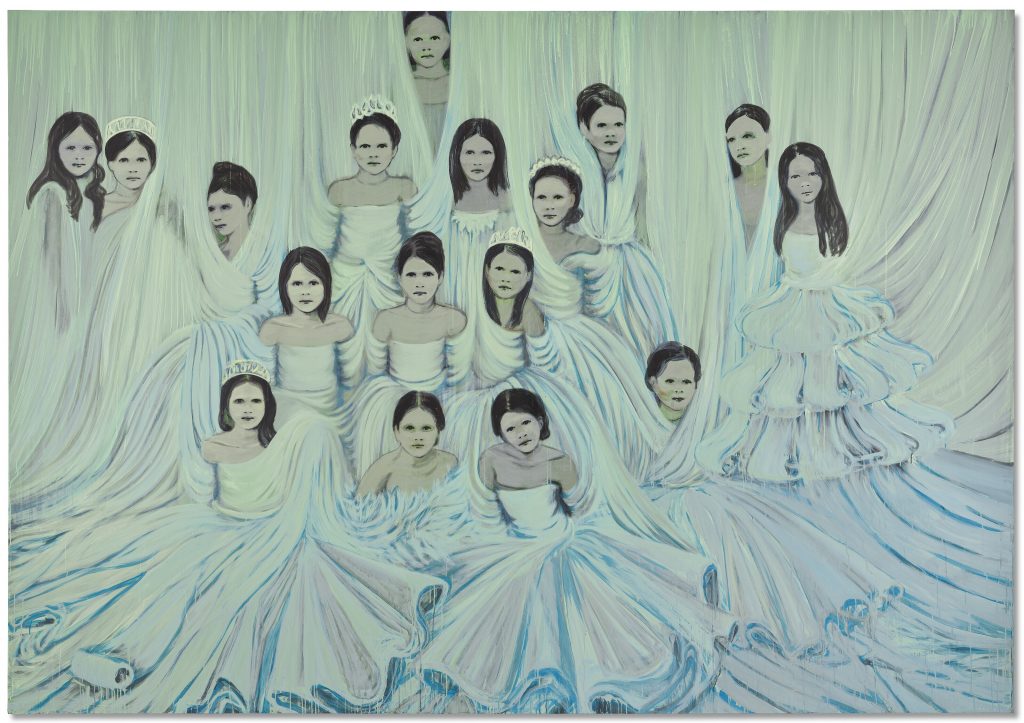

Tabouret’s market will be tested by her 2014 painting, Les débutantes (blanc lunaire), estimated at £250,000 to £350,000 at Christie’s. Another version of the painting fetched $388,454 at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in October 2021.

“It was just truly mindless for a while,” the auction executive said about the feeding frenzy in the ultra-contemporary market. “I feel like there’s a tiny, tiny bit of sense creeping in, people questioning why they’re spending so much on these things.”