Wet Paint

Wet Paint in the Wild: Fort Gansevoort’s Adam Shopkorn Travels to the Canadian Arctic for One Very Chilly Studio Visit

The owner of Fort Gansevoort gallery shows us a week in his life.

The owner of Fort Gansevoort gallery shows us a week in his life.

Annie Armstrong

Welcome to Wet Paint in the Wild, an extension of Annie Armstrong’s gossip column wherein she gives art-world insiders a disposable camera so they can give us a peek into their corner of the madcap industry.

The dedication of some art professionals astounds me. One of those dedicated professionals is Adam Shopkorn, the indefatigable owner of the New York gallery Fort Gansevoort, which stages daring programming in a former U.S. Army Fort in Chelsea. He told me he’d be visiting one of his artists, Shuvinai Ashoona, who lives in Kinngait in the Canadian Arctic (you may have seen her fantastical drawings at the Venice Biennale). I couldn’t resist handing him a disposable camera and praying that the film would survive the intense conditions.

While everyone was at Frieze in London, I was at Freeze (visiting the Inuk artist Shuvinai Ashoona, who lives in the small community of Kinngait located in the sparsely populated territory of Nunavut in the Canadian Arctic).

Going to visit Shuvinai Ashoona is no small feat. In order to get to Kinngait, I had to fly from New York to Ottawa, Ottawa to Iqaluit, and Iqaluit to Kinngait. Landing in Kinngait means the pilots have to see Kinngait. Our first attempt was unsuccessful—the pilot announced the plane would have to fly back to Iqaluit—so we tried Kinngait again the next day, which proved successful. I am not quite sure where this is but it looks like a beautiful abstraction of the sun setting over the Canadian North.

I always liked how the Toronto Raptors slogan is “We the North.” Kinngait’s slogan should be “We the Seriously North”.

Here is a beautiful Fischli and Weiss photograph… just kidding, it’s just a Canadian North airplane. Canadian North’s airplanes are often half-cargo, half-passenger, and there’s a giant door separating the two inside the cabin. This is essential for providing goods to the remote Inuit communities.

Here is a stop sign in Kinngait on one of my daily walks. I was told not to walk alone because of the polar bear sightings in town, so I made it a quick one. The first language in Kinngait is Inuktitut. Though I am unable to read or speak Inuktitut, the language looks quite beautiful to me when written.

Artists who work at Kinngait Studios, part of the West Baffin Cooperative established in 1959, punch in and punch out each day. They arrive at 9 a.m. and leave at 5 p.m., just like Dolly Parton… one of Shuvinai’s heros.

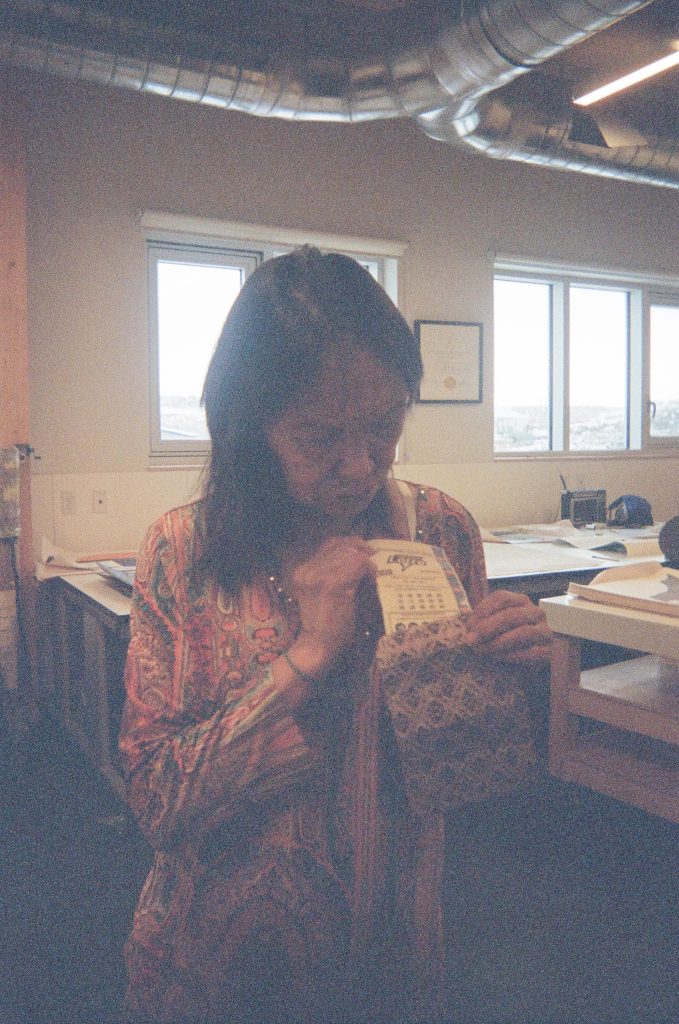

This is my first time meeting Shuvinai in person. She took out a lotto ticket, which I think was from Vancouver, and showed it to me. It was unclear to me whether or not she had won. With her inclusion in the Venice Biennale and her artwork being shown in institutions all over the world, she is already a BIG winner in many eyes.

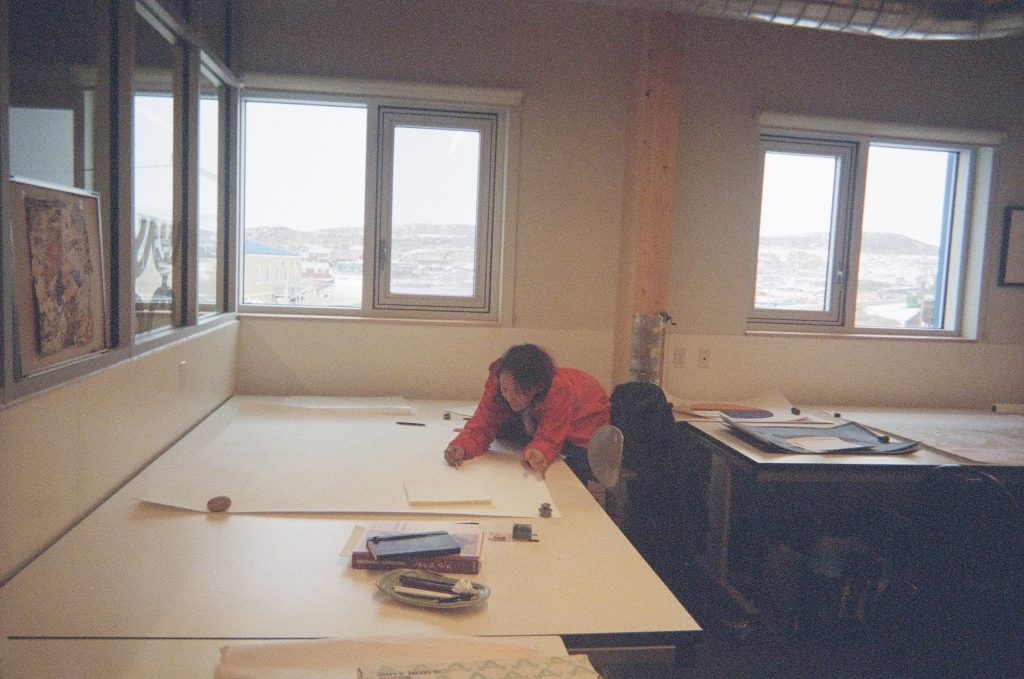

Shuvinai is an all-star within the West Baffin Cooperative. With that comes a large desk and prime real estate. Her drawings are often quite big and she really gets up on top of them when she’s working. The studio has beautiful views as it sits on top of a hill. On my previous trip to Canada I had the opportunity to see her impressive survey exhibition at the Art Gallery of Ontario. It was insightful to see the place where all those wonderful drawings started.

Here is Shuvinai lying on top of her drawing while working.

Audrey Hurd, the studio manager at the arts co-op in Kinngait, invited us back to her place after dinner. She had an old record player and some great records. That night, I learned how good the B-52’s are, and we each had to make a record selection. I selected Boy George. William Huffman, who is the head of West Baffin Arts Cooperative, is seated with his legs crossed on the couch. He organized this trip for me up to Kinngait and I am forever grateful to him for showing me this magical place and community.

In 2015, the Kinngait school burned to the ground, which was a tremendous hardship for the whole community. It took three years to build a new school. Their gym is incredible and brand new. I shot around with the students and played Elijah one-on-one. Elijah is supposedly the best basketball player in Kinngait.

On the last day in Kinngait, before traveling back to Iqaluit to get to New York, a local offered to drive us around town. Here, she took us to the town’s park, which sits right on the Arctic Ocean. I was told that the rocks you see are some of the oldest in the world.

Here’s the park which doesn’t get much use nine months of the year, but from what I understand is quite crowded during the summer.

Inside this building is a lunch counter that serves great burgers, grilled cheeses, and fries. Service is definitely not in a New York minute, so one has to be patient.

I thought my Sorel boots would be perfect for Kinngait, but they had zero traction. Luckily, the supermarket sold snow boots. Here’s me with my new pair of boots standing on some of the oldest rocks in the world with the Arctic Ocean in the background. Although many of my photos were duds (some came out completely black), the memories of this incredible trip will stay with me forever. I cherish the time I spent observing Shuvinai Ashoona at work in her studio and learning more about daily life in Kinngait—a place of tremendous beauty and inscrutable challenges. This is the place that nurtures Shuvinai’s creativity and inspires much of the imagery that appears in her work. Though many will not have the chance to travel here, Shuvinai’s intricate drawings provide glimpses of this multifaceted world through her eyes.