Museums & Institutions

‘It’s a Bittersweet Situation’: Collector Christian Levett Opens Up About Rededicating His Museum to Women’s Art

The new museum is slated to open in June.

The new museum is slated to open in June.

Sarah Cascone

The National Museum of Women in the Arts, the world’s first and only museum dedicated exclusively to women artists, recently reopened in Washington, D.C. after a two-year renovation. Sometime next June, it will finally have a European counterpart, when commodities trader-turned-art collector Christian Levett unveils the Femmes Artistes du Musée de Mougins (Women Artists of the Mougins Museum), his reimagined private museum in the village of Mougins in Southern France.

Levett, who has been collecting art for nearly 30 years, first opened the space, hidden away in the hills about a 10-minute drive from Cannes, as the Musée d’Art Classique de Mougins (Mougin Museum of Classical Art) in 2011. The institution was created to showcase his ever-expanding collection, pairing antiquities and classical art with works by Modern and contemporary masters that illustrate a clear classical influence.

The Levett Collection has had many different iterations over the years, as Levett’s tastes and interests have grown and otherwise changed. His holdings of Old Master paintings, for instance, largely went to his ex-wife in their 2013 divorce. But the biggest change has come over the past three years, with the collector shifting gears to focus on women artists.

At the end of August, Levett closed the doors of the Mougins Museum for the last time, and emptied the galleries, which have welcomed some 250,000 visitors over the past dozen years. The bulk of the museum’s collection is being offered by Christie’s at a series of six sales in New York, London, and online that will take place over the course of a year, beginning in December.

The Mougins Museum of Classical Art, which opened in 2011 to showcase the collection of Christian Levett, closed at the end of August, in anticipation of its transformation into the Femmes Artistes du Musée de Mougins. Photo courtesy of the Mougins Museum of Classical Art.

“A Collecting Odyssey: Property From the Mougins Museum of Classical Art” will feature some 400 lots, with works from ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome; Neo-Classicist masterpieces; classically inspired Modern and contemporary artworks; and selections from Levett’s collection of ancient arms and armor, which is the world’s largest in private hands.

When the museum reopens, visitors can expect to see works by Louise Bourgeois, Helen Frankenthaler, Grace Hartigan, Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Joan Mitchell, Leonor Fini, Barbara Hepworth, Alma Thomas, Joan Semmel, Howardena Pindell, Cecily Brown, Marlene Dumas, Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, and Carrie Mae Weems, among others.

Ahead of the coming auctions, we spoke with Levett about what drew him to collecting art, how he came to focus on women artists, and what to expect from the new Mougins Museum.

Sarah Lucas, Someone Dropped a Bomb on Me (2020). Collection of the Mougins Museum.

What were your first experiences with art, and what set you on the path to becoming a collector?

I collected coins and medals as a child. I had medals for my father who had fought in the Malayan campaign in the Second World War, and from other family members going all the way back to the First World War and the Boer War in the late 19th century.

Growing up, I always visited historical places on our family holidays, so I always had an interest in history. But we went to churches and cathedrals. When we came into London, we would go to museums like the British Museum, the Science Museum, the Natural History Museum, or the Wallace Collection—we never went to art museums.

When I was 25, in 1995, work took me to live in Paris briefly. I thought it was a great opportunity to sort of give myself a self-education in art history. I’d been interested in medieval history, interested in the wars, interested in Roman and Greek history, so art was kind of the piece of the history puzzle that I was missing.

I would spend my Saturday and Sunday mornings visiting the museums. I had this particular affinity for the early Dutch and Flemish 17th-century galleries at the Louvre.

The first two artworks of any real value that I bought were an early-17th-century painting of a fire scene in Delft by a little-known Dutch artist called Egbert van der Poel, and a 19th-century painting of a cavalier by Ignacio Escosura, which was an exquisite picture.

I paid 100,000 French francs, or about £10,000 ($20,000) at the time, for the Van der Poel, and about 70,000 French francs, or £7,000 ($14,000), for the Escosura. The Escosura is now worth about £1,000 ($1,200), and the Van der Poel is probably worth about £15,000 ($18,000) to £20,000 ($24,000). So they weren’t the greatest art investments—but they weren’t meant to be. I bought two paintings that I really, really liked. And they are still great paintings.

A few years ago, I gave the Van der Poel to one of my nephews, who hangs it in his pool room. And I gave the Escosura to my mother-in-law, and it hangs in her living room.

A selection of works from Christian Levett’s collection at the Mougins Museum of Classical Art in France, including detail of Yves Klein, Blue Venus (1962/1982); a Roman marble torso of Venus (first to third century C.E.); and Andy Warhol, Birth of Venus (1984). Photo courtesy of the Mougins Museum.

So then for the next 15 years you were collecting. What made you then decide to open up your own museum and why did it focus on classical art?

I’d been collecting different artworks—Old Masters, Impressionist drawings. And when I started collecting Roman, Greek, and Egyptian antiquities, I started then to see artworks from the Baroque period through to contemporary times that had classical themes.

I started to think, “If I have a Roman torso of Aphrodite, wouldn’t Yves Klein’s 1962 Venus look kind of cool against that in my house?” And then that just kept happening over and over and again. You don’t necessarily imagine artists in the late 20th century looking back to the classical period for themes and inspiration, but it has happened consistently over the last 400 years, including still today.

In 2009, I decided to open the museum because I tend to collect way over and beyond anything that can be just shown at home. Normal collectors, if they decide to upgrade something on their wall, they sell the picture on the wall and they buy a new one. I belong to the category of collectors who are addicts and fanatics, and end up with storage facilities full of the stuff.

It was clear the collection needed to be shown to the public, so it could be studied by scholars, shown to school children. When I decided to open a museum, I considered London, where I lived, and Mougins, where I had a house and a restaurant.

And Mougins was interesting because many of the hilltops around the south of France had Roman settlements and temples, and many of the towns around the south of France were Greek trading posts. So there was a Greek overlay as well as a Roman overlay to the area. Plus, Picasso spent the last 12 years of his life living in Mougins. So I thought, rather than set up a new museum in London, we could be a big fish in a small pond in Mougins.

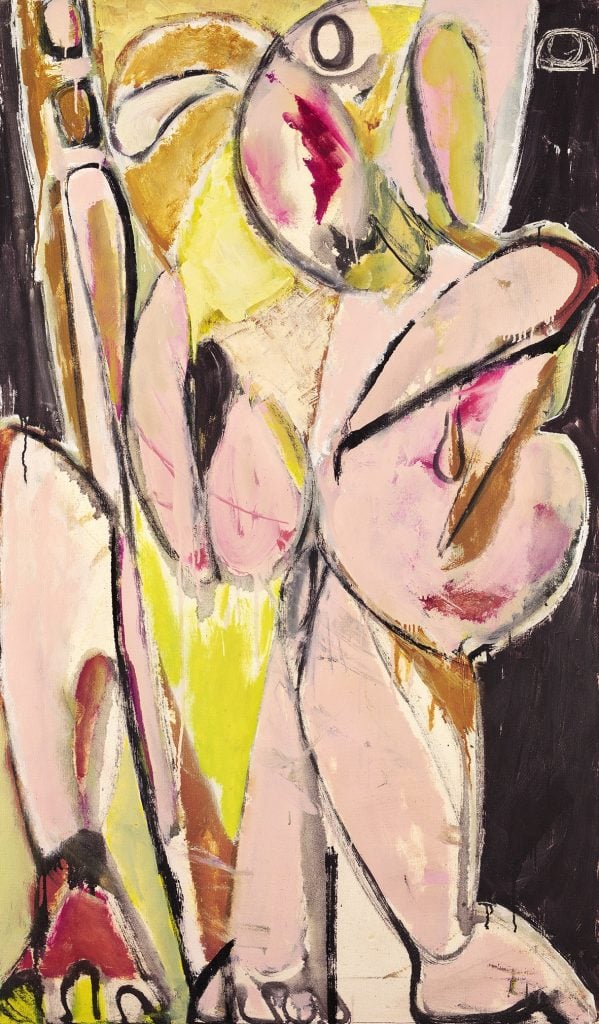

Lee Krasner, Prophecy (1956). Collection of the Mougins Museum.

And how did you come to shift the focus of your collecting efforts during lockdown, as you started looking more into the work of the women Abstract Expressionists?

About eight to 10 years ago, I decided to focus my collecting more towards Post-War art. I wasn’t discriminating between male and female artists at this point. So I bought artworks by Alexander Calder, David Smith, early Willem de Kooning, Wayne Thiebaud. And then I bought Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, and Damien Hirst, but also Joan Mitchell, Helen Frankenthaler, Lee Krasner, Cecily Brown, Bridget Riley, and Tracey Emin.

I started to get more interested in the female side. I got the catalogue from the retrospective of Elaine de Kooning’s portraits at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington in 2015. And then there was a show that came out in Denver about female Abstract Expressionism, which became this sort of seminal show, then the following year there was the book Ninth Street Women.

I had already been looking at Elaine de Kooning and Grace Hartigan, but the Denver catalog also had the CVs of the other female artists of the period. I had been lucky enough to buy Mitchell, Frankenthaler, and Krasner early-ish, but by then they were really accelerating in price, to the low millions.

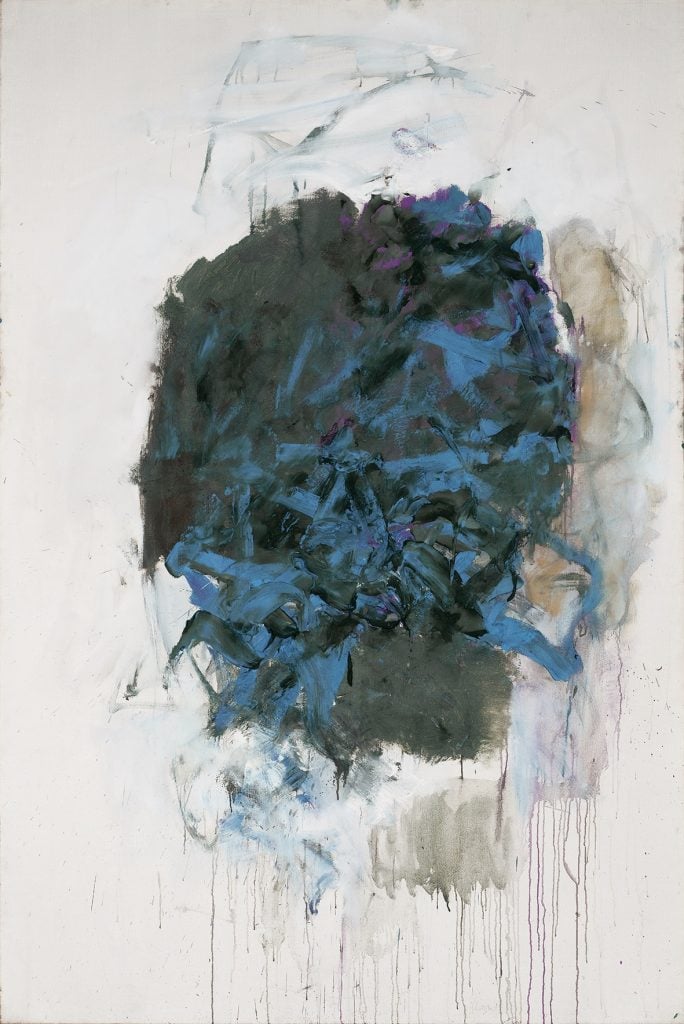

Joan Mitchell, Rufus’s Rock (1966). Collection of the Mougins Museum.

The other great female painters of the period—Yvonne Thomas, Ethel Schwabacher, Hedda Stern—they were trading at about $50,000 to $150,000 a picture. And these were major, major artists of the period, shown at the major galleries, exhibiting at the major museums, being bought by major collectors.

So I thought, “Well, let’s see what’s out there.” There happened to be quite a lot of amazing pictures on the market at that particular moment in time. Around the beginning of lockdown, I ended up buying 12 pictures from a collection out of Minnesota. I spent my time accumulating many of the other female artists of Abstract Expressionism.

I realized there was an opportunity to put together a museum-quality collection for what was—to me at least—an affordable amount of money. For $100,000 a picture, you can buy 50 pictures with the $5 million you would spend on one Cecily Brown. She is one of the most important painters of our day, and that’s a perfectly reasonable price, but that makes these other artists seem incredibly underappreciated and incredibly undervalued.

People often say to me, “Why aren’t you collecting the men of the period?” But you can’t buy a Jackson Pollock or 1950s Willem de Kooning unless you want to lay out $100 million to $200 million—and that’s assuming you can actually ever find one.

The Guttmann Mouse Helmet (ca. late 2nd–early 3rd century A.D.) Photo courtesy of the Mougins Museum.

How did you come to decide to sell the collection from the current museum?

I couldn’t just take everything out of the museum let it all sit it in storage again. We had these incredible pieces that had been loaned to some of the world’s greatest museums, all over the world. The mouse helmet that’s coming up for sale in January, I had on loan to the Met for five years. A helmet that will be in the second military sale was at the Getty for two years, and there’s a marble bust of Odysseus that’s coming up that was in the Troy exhibition at the British Museum. It’s one of the only Roman busts of Odysseus that’s known anywhere.

Members of Christie’s have visited the museum over the years because some of the antiquities and artworks came from Christie’s originally. Mougins is basically an old medieval village that looks down on Cannes and the sea. It’s also on the route between San Tropez and Nice Airport. So it’s always been an easy museum for anyone that’s interested in art or interested in my collection to stop into.

So Christie’s was well aware of the museum and its collection. When I spoke to them, they said, “We would love to do this sale instead of putting all this stuff in storage. Have you thought about doing a series of sales?” And it will be six sales over the course of a year.

The first sale, on December 7 in London, is really what the museum is all about, the ancient versus the Modern. And there will be another sale like that in New York later next year. The second sale, on January 30 in New York, is one of two sales dedicated to military items. And then there’s two sales which are just dedicated to antiquities.

These are pieces that really need to be seen, and potentially be bought by museums—or major collectors who will hopefully continue to loan them to museums. And this an impossible collection to rebuild at that point. It is a unique opportunity for people to buy incredible, museum-quality antiquities with great provenance that have already been on public view for the last 12 years and been loaned to other major museums.

Did you consider opening a second museum dedicated to women? And what can visitors expect from the reimagined Mougins Museum?

That would be too much for me personally to take on. My collecting habits have changed, so now it’s time to let these go to new homes of people who are busting with enthusiasm about antiquities and classical artworks.

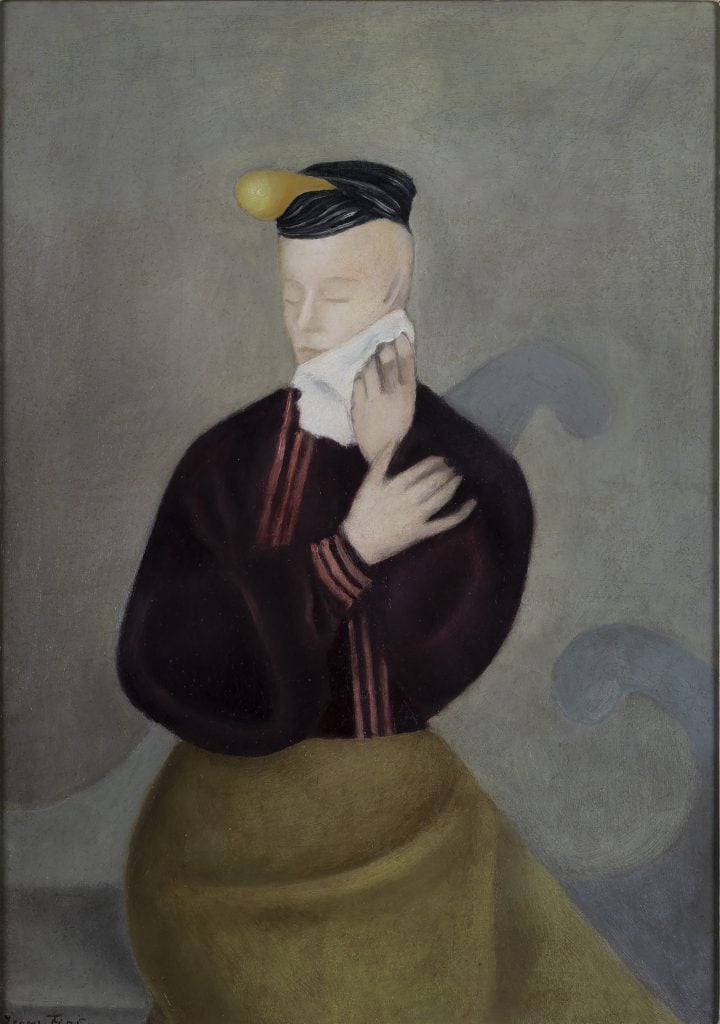

Recently I’ve been looking at French female Impressionism, female Surrealism, and going back pre war now. So the new museum won’t be entirely focused on Abstract Expressionism. It’ll be late 19th century through to contemporary.

Tracey Emin, Hurricane (2007). Collection of the Mougins Museum.

Do you know how much of the work in the previous Mougins Museum collection was by women?

Quite small. I had a Bacchus picture from 1983 by Elaine de Kooning, which isn’t going into sales. There was a 1957 statue by Dorothy Denner, who was David Smith’s first wife. She had a retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1965, and the Cleveland Museum in 1993, but is another hugely overlooked artist in recent years. And I had a Tracey Emin in the museum, and that’s not going into the auction. Basically, I am keeping the artworks by the female artists.

I’m selling the whole holdings of the classically themed artworks from the Baroque period through to contemporary, and about half of the antiquities. The other half, some of them I’m going to keep, and some I may donate to other museums.

Damien Hirst, The Severed Head of Medusa (2013). Photo courtesy of the Mougins Museum.

Do you have a favorite work that is going to be in the upcoming Christie’s sales?

Out of the contemporary artworks, the Damien Hirst Medusa head that was in his Venice “Shipwreck of the Unbelievable” exhibition in 2017. It is an incredible work of art. And it’s been in several museum exhibitions, at the Ashmolean in Oxford, in Rome at the Borghese, in another exhibition in a museum in France, and at the Mougins Museum.

Out of the antiquities, there’s a multifigure sculpture of Pan and Bacchus playing. It is exquisitely detailed and fragile. It’s unbelievable how this piece survived 2,000 years in the condition that it’s in.

And do you feel any sadness to part with some of these works?

Hugely! It’s a bittersweet situation. But I can’t just keep stacking things up in storage. I’ve got to let this fanaticism of mine calm down. And also, I can’t afford to just buy endlessly, because I retired from my career in finance in 2016, and I’m not trading these days. But I bought these pieces with passion and enthusiasm, and for years I never really thought I’d sell anything, so it’s painful.

A Roman marble group statue of Bacchus, Pan, and Eros (ca. early 3rd century A.D.). Photo courtesy of the Mougins Museum.

In terms of the new museum focus, how important is it to you to celebrate women artists and do you see a new mission for the museum to expand the art historical canon and acknowledge women’s cultural achievements?

I think the museum will do that in its own right.

I’ve focused on buying what I think are great works of art. I only buy beautiful paintings by super high-quality artists. I focused on the women because I thought it would make a cohesive collection and sort of tell the story of great female artists throughout the Abstract Expressionist period, and I’ve since expanded that to a period of, let’s say, 140 years.

But many of these artists just wanted to be known as artists, not as somebody’s wife, and not whether or not they were male or female.

I’m not really in a position to talk about the social and feminist side of the history of women’s arts. I’m not a woman myself. I haven’t really studied that too much. We plan to have all the wall labels and a catalogue written by women curators who are well versed in the subject and in a better position to write the narrative of the social history of women’s art better than I can personally.

The purity of what I’m doing is that I’ve wanted to buy amazing works of art, and I feel that I’ve done that, and they’re on the theme of being created by female artists.

I hope when people walk in there and see the quality of artworks, they’ll walk out and think to themselves, “That was amazing.” And hopefully visiting a museum where all the artworks have been by female artists makes them stop and think “How did we ever reach a point where so little of the work on the walls of museums or in auctions was by female artists?” That’s really what I want people to think.

Leonor Fini, Portrait féminin n. 9 / Ritratto di signora seduta (1936). Collection of the Mougins Museum.

What are your plans for hanging the collection, and also for temporary exhibitions?

With the collection, I’ve got more paintings than can be housed in the museum—and I also give private tours of my house in Florence to museum groups and university groups. So we’ll rotate things around regularly.

We’ll also do small exhibitions as well. One idea is for a show of Elaine de Kooning portraits, which would be the first one in Europe. Another potential exhibition is Elizabeth Columba, a French artist from Martinique who has been working in New York for a long time now. She paints these spectacular pictures in an Old Master style and they have incredible fabrics. But we’re still undecided what the initial exhibition will be.

Berthe Morisot, Jeune fille étendue (Young Girl Lying Down), 1893. Collection of the Mougins Museum.

And how much work needs to be done, in terms of renovating and reinstalling the museum?

The builders and everyone are aiming for June at this point. And we don’t foresee a problem with that, because the infrastructure, the air conditioning, lighting, that kind of thing, was already in the museum.

The museum was full of cabinets and full of objects, and all the cabinets have already been stripped out. But we haven’t had to gut everything and start again, so it should be relatively quick.

And in terms of museum staff, will there be any shift toward people who have more expertise in the new subject matter?

The main staff who manage the collection for me have been through this refocusing themselves as I’ve accumulated these new artworks over the years. So they’re already pretty well versed in this area.

We do need to bring in a consultant or two to work with us on things like labeling and storyboarding and laying out the museum in the new year. I have spoken to someone who is a senior curator who’s done many large-scale shows at a very well-known museum who hopefully will be working with us on the development of the new museum. She hasn’t formally signed yet, so I’m not in a position to say who at this point, but she’s the perfect person!

More Trending Stories:

Four ‘Excellently Preserved’ Ancient Roman Swords Have Been Found in the Judean Desert