A little more than a week ago, I wrote a review of an art show by the artist and TikTok sensation Devon Rodriguez, best known for live drawing subway riders. He is, by some measures, the most famous artist in the world, with many millions of social media followers. He did not like the review.

It went up on a Friday. On Saturday morning, I woke up to a tidal wave of anger from Rodriguez on Instagram, tagging me across scores of posts. Hundreds of his followers went on the attack, swarming my Instagram: “loser,” “hater,” “pathetic,” “jealous,” “your a dick,” and on and on and on. There were many creative variations on “kill yourself.” Others said they were going to get me fired, or said things like, “we are going to start a cancellation campaign against you.” A large number thought that defending Rodriguez meant calling me bald, ugly, fat, or whatever they thought could get under my skin. Most didn’t seem to have actually read my article. A contingent went after my wife. “Some women will do anything for money,” one commented. That one was funny, actually.

After a few days Rodriguez ceased tagging me, and the wave of hate cooled down. “@benstoppable love will always outshine being a hater, I hope I taught you that today,” Rodriguez posted.

Screenshot of a post by Devon Rodriguez to Instagram stories.

Meanwhile, I also received an urgent email from UTA Artist Space: “Devon (who we represent) nor UTA was given a chance to respond to this very negative and one-sided article.” I wrote back that I had never heard of an artist demanding to comment on a review in advance, but that if Rodriguez or UTA wanted to write a reply, we would publish it.

It’s not the first time that an artist has been mad at me—only the first time that an artist with this particular type of fame has gone out of his way to unleash his fans in this way. It’s also not anywhere near the worst or most important thing going on in the world, obviously. Nevertheless, I do think it raises some larger issues worth thinking about.

Screenshot of a post by Devon Rodriguez to Instagram stories.

A Shifting Attention Economy

In his torrent of posts, Rodriguez takes big issue with my opener: “Devon Rodriguez is almost certainly the most famous artist in the world, at least on one level,” I wrote. “Almost no one I know has ever heard of him. Except if you say: ‘he’s the painter who draws people on the subway, from TikTok.’ Then sometimes they will light up with recognition.”

His response: “no one he knows has ever heard of me… as if the people that HE knows are more important than everybody else in this world that follows me.. Sorry that I’m not a part of your pretentious circle @benstoppable.”

Screenshot of a post by Devon Rodriguez to Instagram stories.

But the spirit of the article is clearly, if you read it, the exact opposite of what Rodriguez seems to think it is: I’m arguing that traditional art circles should take the phenomenon seriously, and think through what is really going on with this kind of art career. Rodriguez has a lot of cultural clout—but the fact is that most people who go to museums and galleries or who regularly read about art haven’t heard of him.

This is a very weird feature of the cultural present. Instead of art that gains traction over time via traditional channels and then breaks out to a wider audience, there are now regularly art phenomena that get explosively popular with an immense audience, leaving art institutions and everyone else to sort out what a particular cultural trend means after it has already happened.

Screenshot of a post by Devon Rodriguez to Instagram stories.

Rodriguez is acting as if he is being unfairly scrutinized when he is one of the most influential artists out there, someone who works with A-list celebrities, who the New York Times says has made as much as $30,000 a day working with mega-brands like Cheetos, who has numerous press agents working to stage-manage his image, who is the ambassador for what contemporary art is to the largest possible audience—he even teaches a Masterclass on realistic portrait painting!

“Dude has PRs putting him in the room with the president and he’s acting like you are gatekeeping him,” someone wrote me. (I should mention that I’ve received a lot of support too.)

In fact, the only way I can understand Rodriguez’s incredibly thin-skinned reaction to my article is that he has managed to rise to this status of apex visibility without any kind of critical writing about him at all. It’s all just been feel-good profiles, so that the first critical word feels like a huge crisis. That’s a relatively new kind of situation for an artist to be in, and worth analyzing.

Screenshot of a post by Devon Rodriguez to Instagram stories.

Art Criticism and Parasocial Relationships

“If you don’t have anything nice to say, don’t say anything at all” was a phrase that commenters repeated a lot. Rodriguez’s art content makes people happy, so why be “negative?” Quite a few people posted variations on, “what is even the point of art critics?” So let me say what purpose an article like the one I wrote might serve.

First: With regard to the paintings themselves, simply repeating press-release hype isn’t healthy for anyone. It happens all the time that artists get stuck doing whatever first brought them success, and dealers or marketers encourage them to just do the same thing because it’s the easiest thing to sell, thereby undermining what could be a more enduring career.

As I repeat in the article, Rodriguez seems a gifted painter, in a photo-inspired realist style. At the same time, when it comes to the show I reviewed, “Underground,” the subject matter is well-trodden territory. We have 100-plus years of painters doing subway scenes, from Reginald Marsh to Jordan Casteel, so the question of what is different or exceptional about these particular versions of the theme is accented. Maybe this doesn’t matter to his audience, but it probably does matter to people who are interested in painting.

Still, my question was not even this. It was whether the paintings on their own were enough to explain his extraordinary popularity. And the answer to that question is clearly no.

A visitor looks at paintings in “Underground.” Photo by Ben Davis.

That brings me to the second point, which is where the case of Devon Rodriguez is specifically interesting. Basically, I’m arguing that we should think of his social media posts as part of his practice, to be reviewed in and of themselves. These are, after all, not just how he got famous; in some sense they are what he is really famous for. And they are in many cases clearly staged. (There is a long and robust online debate by artists about how real his subway clips are.)

Take his post from October 4, where Rodriguez draws a dancer on the London Underground, who turns out to be Sabrina Bahsoon, a.k.a. “Tube Girl.” “I love your moves—are you a professional dancer?” Rodriguez asks at the climax of the clip as he hands the drawing to Bahsoon, who has three quarters of a million TikTok followers and signed with The Hive modeling agency this year. “Definitely not!” she replies, feigning surprise.

What do his fans think is going on here? That Rodriguez happened to be in London, and happened to come upon another famous TikToker, and that she continued to dance in front of him for 30 minutes as he sat drawing her, with multiple cameras filming the two of them and his drawing pad, as he created a hyper-detailed portrait of Bahsoon that looks like it is sourced from a close-up photo? The comments are full of people marveling: “How did you do that? She wasn’t standing still. Absolutely incredible.” Or: “HOW DO YOU DRAW THEM WHEN THEY ARE MOVING A LOT?” Or: “Your work is amazing. I keep wondering how you keep the pencil steady on a moving train.” Great questions!

Is it “mean” to point out how fake this is? If there’s no criticism of it, here’s what I think will happen: All the marketing companies and PR people looking to piggyback on Rodriguez’s popularity will stuff his feed with more and more cringe celebrity content and half-baked promo ideas until his social-media presence is bled dry of whatever charm it has.

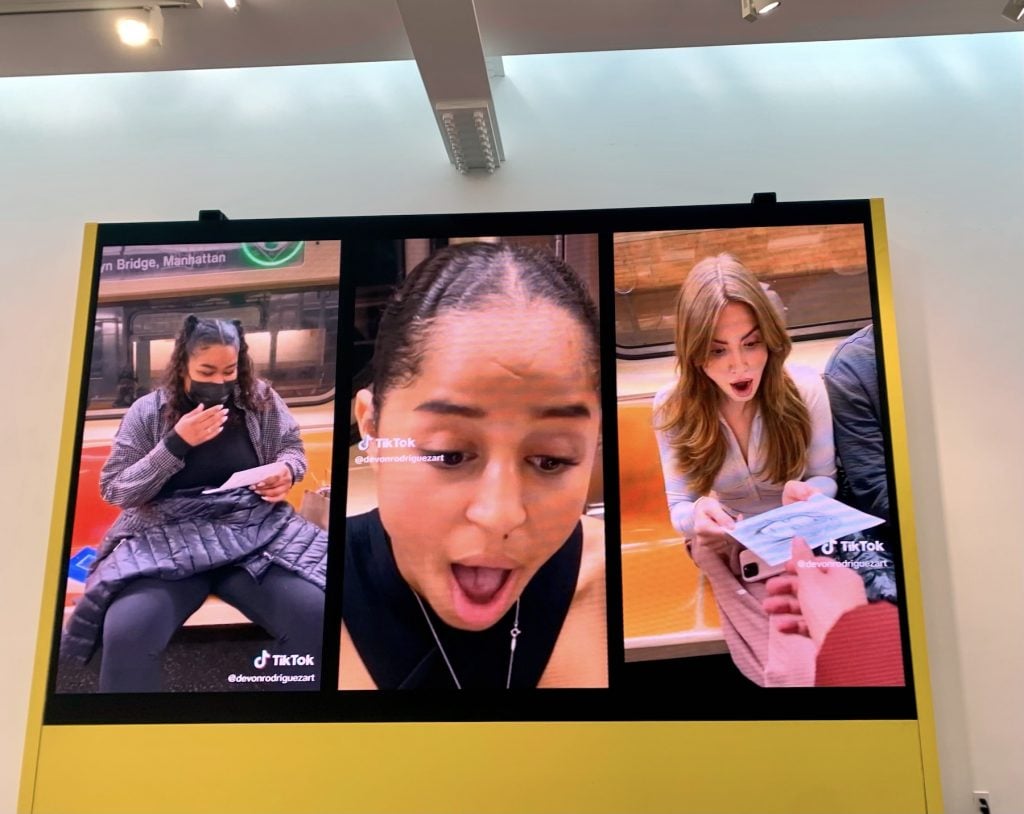

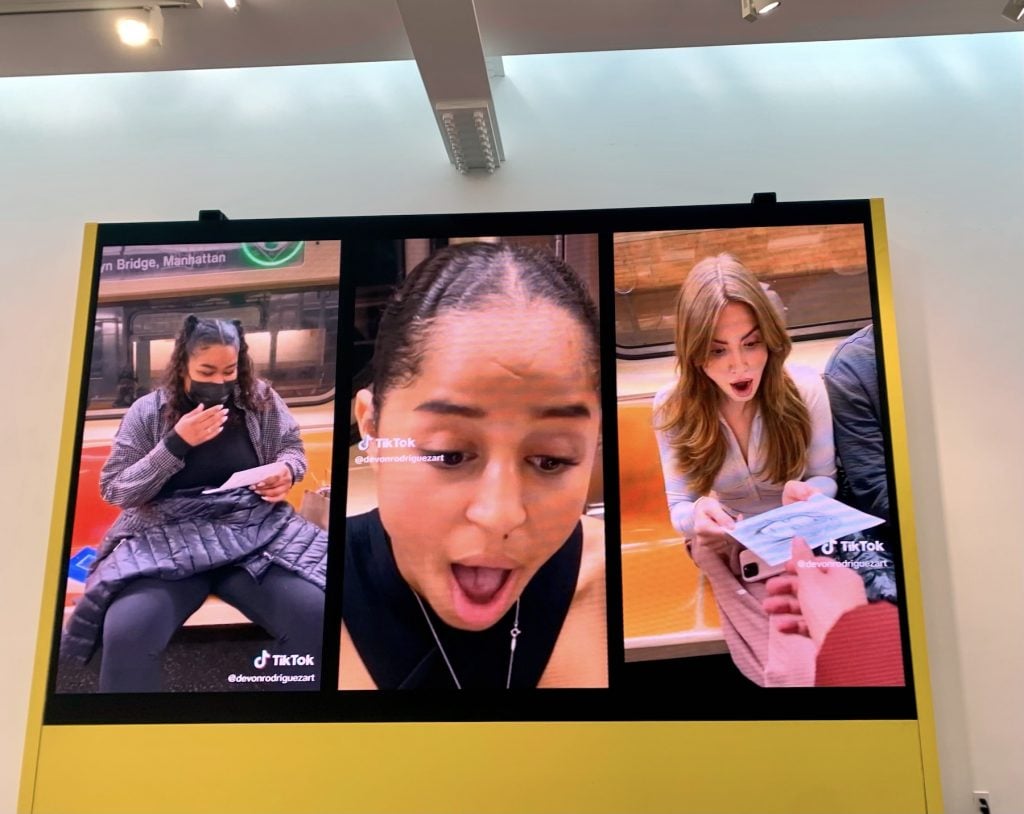

Video by UTA Artist Space telling the Devon Rodriguez story, shown in “Underground.” Photo by Ben Davis.

And meanwhile, a lot of fans coming across art through his channel will get a totally confused idea of how contemporary art-celebrity works. Which brings me to the last and most important answer to the question of why I think it’s worth writing about Rodriguez seriously: Because he is a role model for a ton of young artists, and they deserve an actual assessment of what is going on.

“While Devon is instantly recognizable as a TikTok sensation, his story about his rise as a fine artist—from his childhood in the South Bronx to his Subway paintings and achieving Masterclass-worthy expertise—is something we are incredibly excited to share with the art world and beyond,” his agent, Arthur Lewis, wrote in the press release for “Underground.” Artists’ personal stories have long been part of how art is marketed, from Vincent van Gogh to Frida Kahlo, but in those cases, the artists’ paintings attracted interest first, and the biography became part of its legend as its fame grew. Today, personal biography and narrative are more important than ever in the gallery—most art comes equipped with some kind of story. But social media gives an added twist: Hordes of people can feel as if they have a relationship with a painter like Devon Rodriguez without ever having had any direct experience of his painting at all.

Devon Rodriguez with fans at the opening of “Underground.” Photo by Ben Davis.

“What if he was your son??” someone posted at me angrily. This comment is emblematic. It’s not the kind of thing one normally says about an artist getting a critical review (unless the criticism is extremely over the top and disproportionate to the status of the artist in question). Generally, the point of presenting an art show in public is to see if it can hold the attention of people who don’t directly know you.

But it seems to me that the majority of Rodriguez’s fans are most engaged by his appealing social-media persona, not his actual artworks. If this is the case, then it’s logical to think that it changes how criticism is perceived. His followers feel like I am attacking a person they like, not judging artworks or analyzing a media phenomenon. I think that explains the character of the reaction, which has a level of raw personal anger completely out of joint with what I wrote in my article.

Recently there’s been a lot of writing on the increasing currency of “parasocial relationships” in media, that is, the imaginary, one-sided friendships people develop with celebrities and influencers in their heads. It seems to me that Devon Rodriguez’s title as the “most popular painter in the world” shows what a powerful cultural force a “parasocial aesthetic” can be—it’s probably more powerful (or at least more accessible) than interest in paint on canvas.

All the same, Devon Rodriguez’s art agents and PR handlers might gently tell him that, if one of the things you are selling is likability and good vibes, cheering on this kind of vicious reaction every time you get a review you don’t like is probably not a sustainable career path.