Law & Politics

A New York Judge Has Temporarily Halted a Restitution Case Against Two Austrian Museums

The latest court documents indicate Fritz Grünbaum’s descendants have had difficulty serving the Albertina Museum in Vienna.

The latest court documents indicate Fritz Grünbaum’s descendants have had difficulty serving the Albertina Museum in Vienna.

Adam Schrader

A federal judge in Manhattan has temporarily halted a case brought by the heirs of a Holocaust victim seeking to recover works by Egon Schiele from the government of Austria and two museums in Vienna.

The case was first filed in December 2022 by Timothy Reif, Leon Fraenkel and Milos Vavra—descendants of Austrian Jewish performer Fritz Grünbaum, who was murdered at the Dachau concentration camp in 1941—against the Albertina Museum, the Leopold Museum and the government of Austria.

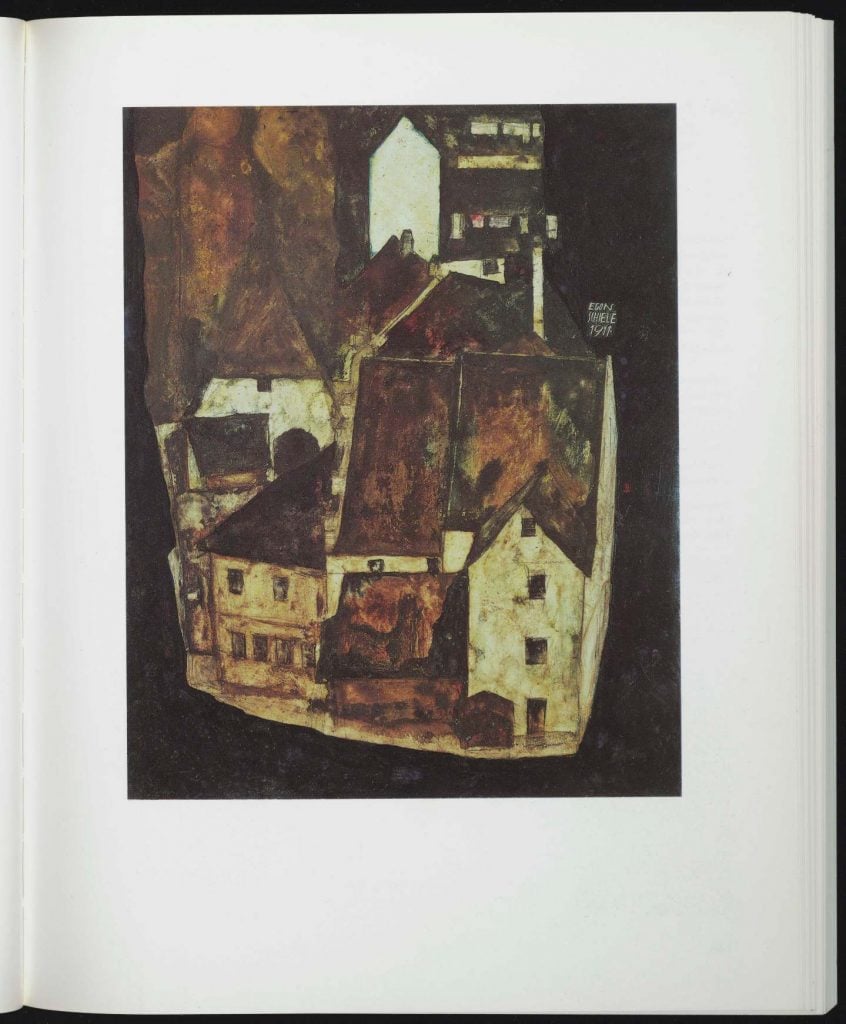

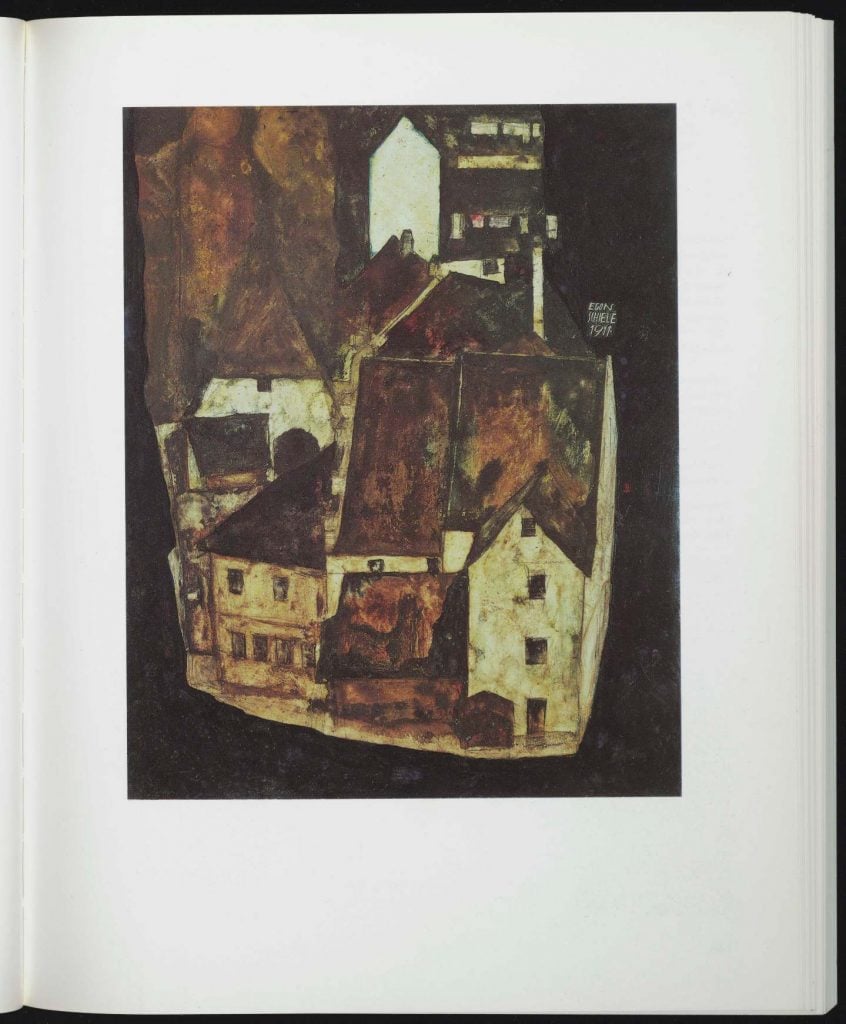

The plaintiffs recently submitted a 67-page amended complaint that adds legal justifications for their claims to recover the works. In total, the family is seeking to restitute 12 works, including Dead City III, Self-Portrait With Grimace (1910), Standing Man in Red Shawl (1913), and Standing Girl With Orange Stockings (1914).

The Austrian government has waived its sovereign immunity by consenting to the lawsuit, the plaintiffs argue in the lawsuit. (Lawyers for the defendants clarified to Artnet this is a contested legal argument raised by the defendants and not a statement of fact.) Representatives of the Leopold Museum have appeared before the U.S. court, moving to dismiss the case against it. But, according to the latest documents, Grünbaum’s descendants have had difficulty serving the Albertina Museum with their complaint, which could prevent the case from continuing through U.S. federal court.

Claudia G. Jaffe, a lawyer for the heirs, last month sent a letter to the judge providing an update on their efforts. She noted that the court had granted a motion to seek “letters rogatory,” a type of formal request to a foreign court for judicial assistance, made through the U.S. State Department.

“We have been in communication with the United States Department of State for a status update on efforts to serve the Albertina Museum but as of this writing, have not received any indication that service of process on the Albertina Museum has taken place,” Jaffe wrote. “We therefore believe service of process on the Albertina has not been completed.”

The stay, a six-month pause in the case, was ordered by U.S. District Judge John Koeltl on October 16, giving the plaintiffs that time to process their lawsuit against the Albertina Museum.

Egon Schiele, Red Blouse (1913). Photo: courtesy of U.S. District Court for The Southern District of New York.

Before his death at Dachau 1941, Grünbaum accumulated a huge art collection of at least 440 works. Among them were some 80 pieces by Schiele that his wife, Elisabeth, was allegedly forced to hand over to Nazi authorities when he was imprisoned. The family has spent nearly two decades trying to recover the works.

In 2005, the family contested the sale of a Schiele drawing, Seated Woman With a Bent Left Leg (Torso) (1917), by the gallery Richard Nagy, but lost the case in 2012 when the Art Dealers Association of America and the Society of London Art Dealers lobbied in favor of the art dealer.

Three years later, in 2015, Reif and Fraenkel filed a lawsuit against Nagy in Manhattan Supreme Court over Schiele’s Woman in a Black Pinafore and Woman Hiding Her Face. At the time, the judge halted any sales until the complaint could be reviewed. “This is not a case of Nazi theft,” Nagy insisted at the time.

Attempts at retrieving works from Grünbaum’s collection have gained momentum over the years, culminating in a flurry of new lawsuits filed beginning in December 2022.

In addition to the case against the government of Austria, Grünbaum’s heirs filed others against the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art in California, followed by lawsuits against the Art Institute of Chicago and the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College in Ohio. The U.S. museum proceedings were later consolidated into one case overseen by Judge Koeltl. The case against the Austrian institutions remains separate.

In September, the office of Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg restituted seven works to the family, who had approached his office for help, including the ones housed at MoMA and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art. Other works turned over to authorities include pieces held by the Morgan Library & Museum, billionaire Ronald Lauder and two from collector Serge Sabarsky. Four of those works were sold at Christie’s 20th Century Evening Sale last week for a total of more than $18 million.

Meanwhile, Bragg’s office has seized other works by Schiele including three housed at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Carnegie Museum of Pittsburgh and the Allen Memorial Art Museum.

A spokesperson for Oberlin clarified by email that the Allen Museum voluntarily handed over its Schiele to the family.

“Oberlin College purchased Schiele’s drawing Girl with Black Hair in 1958. When questions relating to the artwork’s ownership came to light in the years that followed, Oberlin invested significant resources researching the history of its sale and purchase and concluded it had been lawfully acquired,” spokesperson Andrea Simakis said.

“The artwork was bought for the Allen by Charles Parkhurst, director of the museum from 1949 to 1962. As one of the ‘Monuments Men,’ he was celebrated for tracking down and returning art looted by Nazis in WWII. It is inconceivable that Parkhurst would have knowingly purchased any artwork that he believed might have been stolen.”

Egon Schiele, Self-Portrait with Grimace (1910) is listed in court documents as part of Grünbaum’s collection. It now hangs in the Leopold Museum.

The case against the Viennese museums is unique because it involves high levels of diplomacy between the United States and Austria, which has resisted past efforts to restitute works housed at the Albertina.

The lawyers for Grünbaum’s descendants assert that the Austrian government is bound by a number of U.S. laws, as well as the 1955 treaty that gave Austria its independence from the occupation of Allied powers after World War II, to return the works.

“Despite due demand, and despite overwhelming evidence that the artworks were stolen from Grünbaum by the Nazi regime in violation of international law, Austria has refused to return the artworks,” the heirs’ amended lawsuit reads.

“Austrian courts have effectively slammed the courthouse doors shut by imposing impossible financial barriers to claimants and imposing impossible burdens of proof,” lawyers for the family wrote. That burden of proof pertains to the efforts by the heirs to establish provenance and a legal justification for their claim of ownership, which is what led to the amended lawsuit.

Evidence now submitted in the case involves hundreds of pages of supporting documents, including: a 1925 Würthle Gallery catalogue that documents Grünbaum’s ownership of at least 22 artworks by Schiele; a 1930 catalogue raisonné of Schiele’s oils authored by dealer Otto Kallir, documenting Grünbaum’s ownership of additional works including Dead City III (1911); and a Nazi inventory that lists 81 works by Schiele owned by Grünbaum.

Robert Morgenthau, the former district attorney in Manhattan, previously seized Dead City III in 1998 while it was on loan to the Museum of Modern Art, but it was returned to the Leopold Museum two years later.

As for the jurisdiction, the lawyers wrote that, “because most of the artworks were trafficked through New York at a time that they belonged to the Grünbaum heirs residing in New York, New York’s long-arm statute also provides for jurisdiction and a remedy under New York law.”

The Leopold Museum, in a statement on its website noting it would not comment further, claimed that there is no evidence the works in question were confiscated by the Nazis, and that a committee formed to investigate restitution claims concluded in November 2010 that the Schiele works “were federal property”.

“The artworks were sold in the second half of the 1950s by Fritz Grünbaum’s sister-in-law Mathilde Lukacs to or via the Swiss art dealer Eberhard W. Kornfeld (Galerie Klipstein & Kornfeld),” the statement said.

More Trending Stories:

Conservators Find a ‘Monstrous Figure’ Hidden in an 18th-Century Joshua Reynolds Painting

A First-Class Dinner Menu Salvaged From the Titanic Makes Waves at Auction

The Louvre Seeks Donations to Stop an American Museum From Acquiring a French Masterpiece

Meet the Woman Behind ‘Weird Medieval Guys,’ the Internet Hit Mining Odd Art From the Middle Ages

A Golden Rothko Shines at Christie’s as Passion for Abstract Expressionism Endures

Agnes Martin Is the Quiet Star of the New York Sales. Here’s Why $18.7 Million Is Still a Bargain

Mega Collector Joseph Lau Shoots Down Rumors That His Wife Lost Him Billions in Bad Investments