Art History

J.C. Leyendecker Inspired Both Norman Rockwell and a Marvel TV Show. Here’s What You Need to Know About This Master of Illustration Art

The "Leyendecker Look" continues to reverberate.

The "Leyendecker Look" continues to reverberate.

Katie White

America’s greatest illustrator is a title often bestowed on Norman Rockwell—but was it actually his mentor who was the creative genius? The name J.C. Leyendecker (1874-1951) might not have the cachet of Rockwell today, but the German-born illustrator is regarded by print enthusiasts as the true king in the Golden Age of Illustration.

His obscurity is even more surprising when one learns just how renowened Leyendecker was in his day. He was the most sought-after illustrator in America during the 1920. A pioneer of the Art Deco illustration, Leyendecker presented in his images an urbane, well-heeled demimonde that was both of his imagination and resonant with his reality.

With his partner, Charles Beach, Leyendecker swanned through speakeasies buzzing with the likes of Mae West, Gloria Swanson, John Barrymore, Dorothy Parker, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. He would produce well over 400 magazine covers, including 322 covers for The Saturday Evening Post (Rockwell, who is for all intents and purpose synonymous with the historic magazine, fell one shy, producing 321).

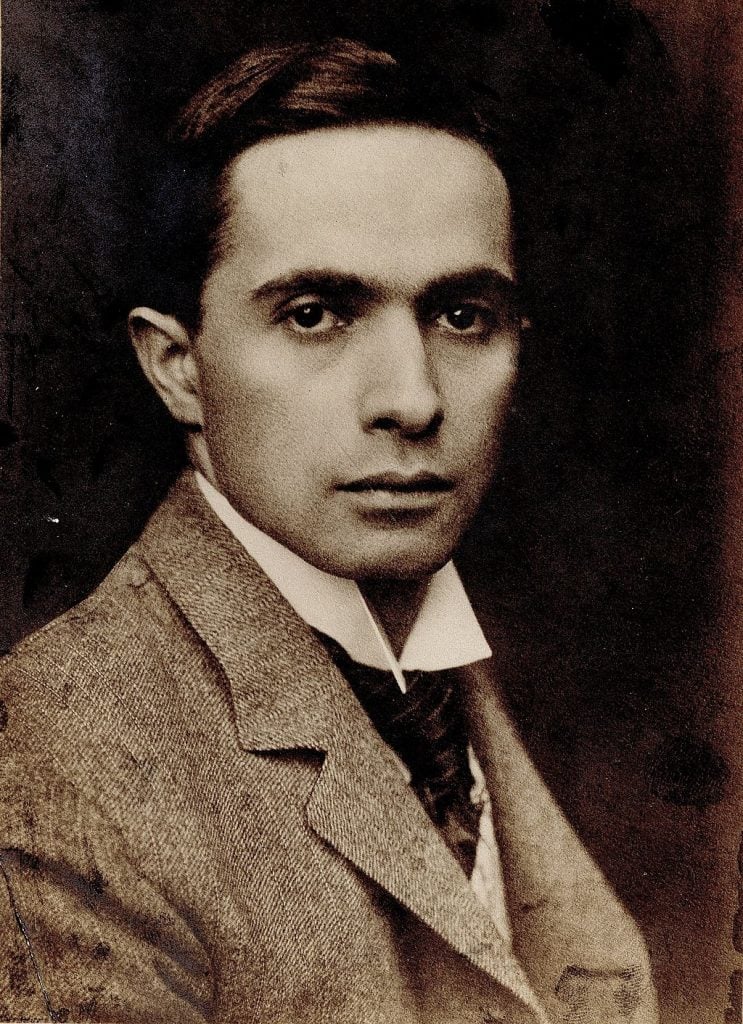

J.C. Leyendecker, artist and illustrator (1895). Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Despite his rather dramatic fall from the heights of acclaim to contemporary obscurity, Leyendecker’s legacy may finally be getting a fresh look. The just-concluded What If…?, a Marvel Comic Universe anthology show on Disney +, featured an eye-catching aesthetic directly inspired by Leyendecker’s Golden Age illustrations, with their clean, stylish lines. “[Leyendecker’s style] is a very difficult style to achieve,” explained Brad Winderbaum, executive producer of the show in an interview. “It’s very painterly. The light spreads in a very unique way.”

The poster for Marvel’s What If…?

So, if you’ve tuned in for What If…? and were intrigued by the visuals or if you simply want to brush up on your Golden Age of Illustration knowledge (and, dare I say, who doesn’t?), here are some facts about the one-and-only J.C. Leyendecker.

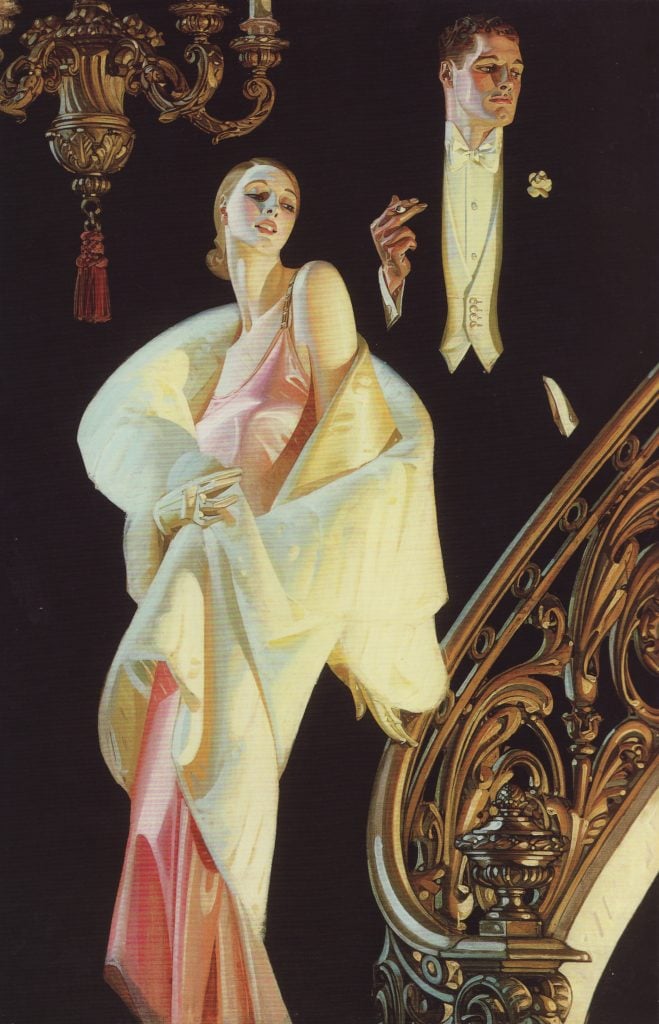

J. C. Leyendecker, Advertisement for The Arrow Collar Man (1932).

While J.C. is not a household name today, his debonair depictions of suited men and glamorous, well-tailored women forged a vision synonymous with American fashion and culture that remains present in our culture up to the present. In fact, it’s a style that illustration historians call “The Leyendecker Look.”

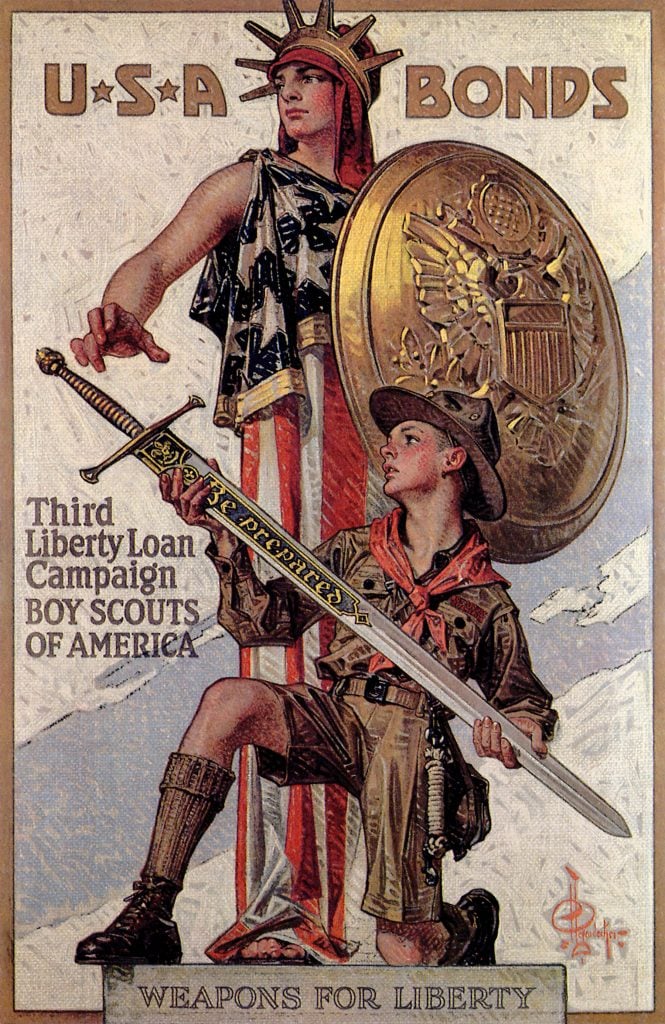

A classically trained painter who studied at the Chicago Art Institute, as well as the Académie Julian in Paris, Leyendecker began creating advertisements for major companies including Procter & Gamble, Kellogg’s, Pierce-Arrow Automobiles, Arrow Collar Clothing, as well as the United States Armed Forces.

His approach was unique and, in many senses, pivotal to the creation of modern branding. He would create recognizable characters who reoccured across a company’s advertisements.

Leyendecker had a specialized medium, too, mixing oils with lots of turpentine to create a thinned paint that allowed him to create luminous and sweeping brush strokes. His magazine covers and editorial illustrations were almost as influential as his advertisement, with his cherubic babies and doting mothers, all All-American collegiate athletes, and idyllic holiday scenes, mimicked by innumerable illustrators who followed him.

USA Bonds Weapons for Liberty poster by J.C. Leyendecker. (Photo by Picturenow/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

“J.C. Leyendecker’s main contribution is to have invented, along with other illustrators, the modern magazine cover as a miniature poster that would engage the viewer, impart an idea, and sell the issue, all within the few moments one browses at the newsstand,” illustration historian Roger Reed has noted.

Thanksgiving Cover of The Saturday Evening Post by J.C. Leyendecker. (Photo courtesy Getty Images.)

Norman Rockwell, who was some twenty years Leyendecker’s junior, regarded Leyendecker as his personal hero. In fact, so deep was his admiration (or some might say fixation) that Rockwell actually moved to be in Leyendecker’s orbit.

In 1914, Leyendecker had bought a home and studio in New Rochelle, New York, along with his partner and frequent model Charles Beach. In Rockwell’s autobiography, My Adventures as an Illustrator, he confesses to having moved to the same area of the small city in order to observe Leyendecker more closely. He even (inexplicably) resolved to mimic the way Leyendecker walked. Leyendecker, for his part, took Rockwell in.

Artistically, Rockwell would scrutinize the older illustrator’s compositions and materials. And, in keeping with Leyendecker’s innovation, Rockwell himself began to create his own cast of characters to populate his images (their aesthetics became so closely aligned that for a period of years they became difficult to discern).

Later, Leyendecker’s career would wane and Rockwell superseded his hero as America’s most famous illustrator. Nevertheless, many of the creative inventions so often attributed to Rockwell originated in Leyendecker’s work.

“Arrow Collars and Shirts” Advertising Poster by J.C. Leyendecker. (Photo by Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

In 1905 Leyendecker would create the “Arrow Collar Man”—a suave, well-dressed, and handsome male character that was used to advertise the Arrow Collar clothing company’s acclaimed detachable collars. Like the “Gibson Girl,” the “Arrow Collar Man” became a famed likeness in its own right. The “Arrow Collar Man” was defined by his impeccable dress and sporting personality. These men Leyendecker modeled most frequently on his lifelong romantic partner Charles Beach (Leyendecker also occasionally used the actor Huntley Gordon as a model).

The figure became so popular that it was known to receive its own fan mail, and it remains among the first recognizable sex symbols in popular culture. Decades after Leyendecker’s death, as more details of his own clandestine romantic life emerged, the “Arrow Collar Man”—with its perfection of exterior appearance and idealized masculinity—came to be embraced by the gay community as a historic embodiment of coded homosexuality.