Art & Tech

Meet A.I.C.C.A., Artist Mario Klingemann’s New A.I.-Powered Robot Dog That Generates—and Poops—Art Criticism

But what is this "performative sculpture" really critiquing?

But what is this "performative sculpture" really critiquing?

Min Chen

Like you, German artist Mario Klingemann has found himself overwhelmed by the sheer volume of art that has been generated by A.I. With the emergence of text-to-image tools in particular, art-making has been automated and commodified, he said, resulting in “an endless barrage of A.I.-created art to consume, critique, or rather, endure.”

“The more the machine can create,” he told Artnet News, “the more the human is pushed into the role of the tired spectator.”

His solution—or more likely, riposte—is, well, more A.I. To help people better interact with art, A.I.-generated or otherwise, Klingemann has developed a robotic dog, which can algorithmically generate critiques on visual artworks so you don’t have to.

Mario Klingemann and A.I.C.C.A. (2023). © Mario Klingemann, courtesy of Onkaos.

The furry pooch, named A.I.C.C.A. (or Artificially Intelligent Critical Canine), has been trained on a corpus of visual art and art writing, making it well-schooled in color, composition, style, and semantics. Using its black-lens eye, it assesses physical artworks, before working with OpenAI’s GPT model to generate a concise piece of art criticism. This text is then printed on thermal receipt paper that is, um, output through the dog’s butt.

A handful of A.I.C.C.A.‘s criticism has been collected on its Twitter account, and includes such gems as: “Art critique is a form of reading, not writing.” Or even better: “Art doesn’t play fetch with approval. It chews the slippers of convention and relishes in the surprise of its own bark.”

The robot was unveiled in June at Espacio Solo in Madrid, with the support of Colección Solo’s Onkaos program, which backs new media projects.

A.I.C.C.A. (2023). © Mario Klingemann, courtesy of Onkaos.

Klingemann, however, is quick to clarify that A.I.C.C.A. is far from an art criticism robot that’s out to replace human critics. It’s more a “performative sculpture,” he said, meant to confront our over-reliance on technology as it tours art fairs, galleries, and museums around the world.

“The purpose of A.I.C.C.A. is less about challenging critics and more about proposing a quirky alternative perspective. It incites thought, even if that thought is whether machines should be contemplating art in the first place,” he explained. “By doing something as personal and specialized as art critique, it stirs up questions around the role A.I. is—and could be—playing in our lives.”

A.I.C.C.A. and its black-lens eye. © Mario Klingemann, courtesy of Onkaos.

Klingemann is well-placed to spark such a conversation. His interest in machine intelligence was kindled early by Marvin Minsky’s seminal 1986 book The Society of Mind, prompting him to experiment with generative adversarial networks beginning in the mid-2010s. Klingemann has made his name on uncanny pieces such as Memories of Passersby I (2019), as much as inventive projects like his autonomous A.I. artist, Botto.

It’s work that has gifted him a view into how A.I. can be as much creative medium, tool, and mirror: “My work offers a reflection, albeit sometimes distorted, of our times, our hopes, our fears as we navigate this brave new world of technology.”

Not that his oeuvre has been devoid of a playful irreverence—A.I.C.C.A., after all, is a dog that, as a press release words it, “defecates” art criticism. According to Klingemann, who built out the sculpture with Madrid-based robotics company Maedcore, it made practical sense to install the printer in the robot’s rear. That it just happened to serve multiple metaphors was a happy coincidence.

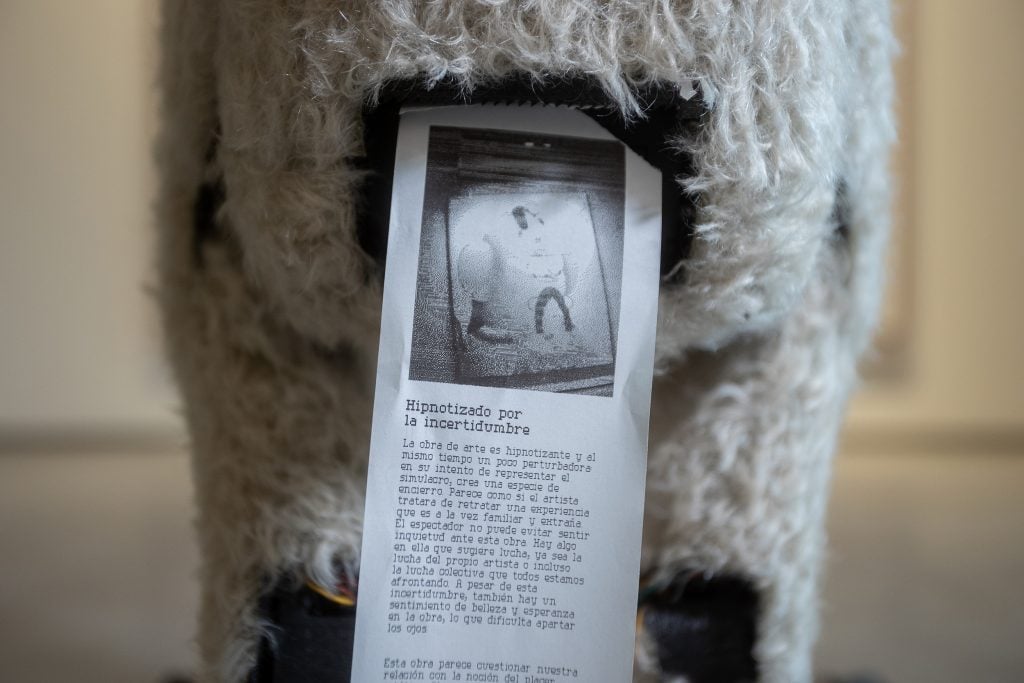

A piece of art criticism generated by A.I.C.C.A. © Mario Klingemann, courtesy of Onkaos.

“One could muse that it’s a witty representation of the current state of A.I. We are being buried under an avalanche of digital diarrhea, which could be politely termed as ‘landfill,'” he explained. “Alternatively, there’s also the slightly cheekier suggestion towards the art world, which—let’s admit it—can occasionally obsess over the art of spouting profound, if at times inscrutable, BS.”

Klingemann himself has had occasion to be surprised at A.I.C.C.A.‘s analyses. Some have hit the mark when it comes to “identifying hidden meanings or creating associations,” he said, while others “bore more resemblance to throwing dart arrows at a board while blindfolded.”

Then again, the robot dog, which Klingemann dubs his “digital child,” remains at least for now a youthful and rather naive machine, learning.

“Aren’t we all just trying to make sense of the world, each in our quirky way?” he added. “I recommend taking its critiques with a mix of open-mindedness and a grain of salt—much like, I daresay, all art critiques.”

More Trending Stories:

A Norwegian Dad Hiking With His Family Discovered a Rock Face Covered With Bronze Age Paintings

An Israeli First-Grader Stumbled on a 3,500-Year-Old Egyptian Amulet on a School Trip