Art Criticism

Why the Opening Ceremonies at the 2022 Winter Olympic Games Were an Artless, Uninspired Dud

The tiny flame was an afterthought.

The tiny flame was an afterthought.

Sarah Cascone

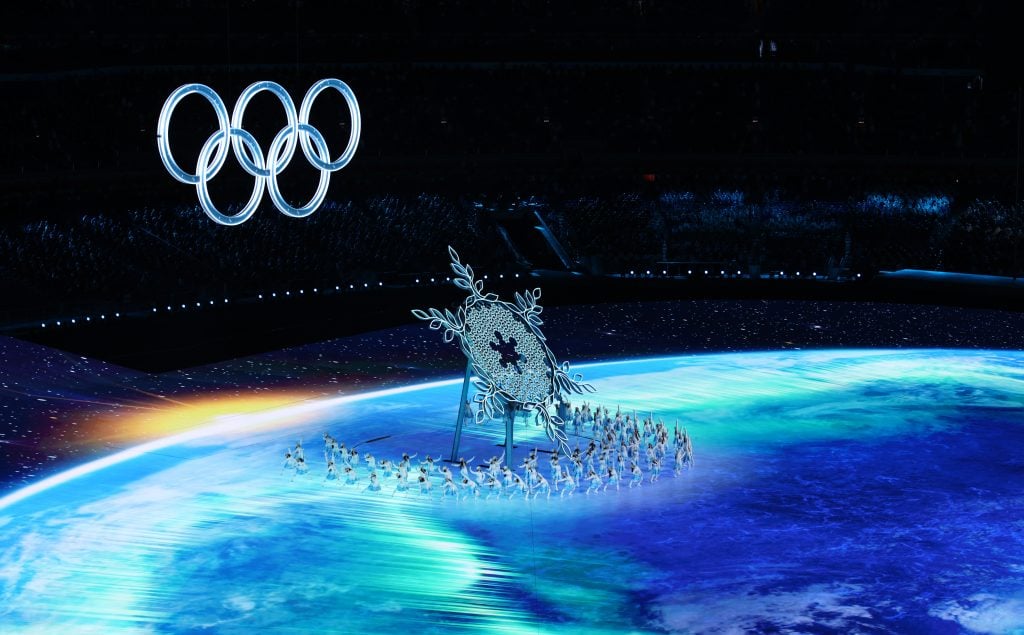

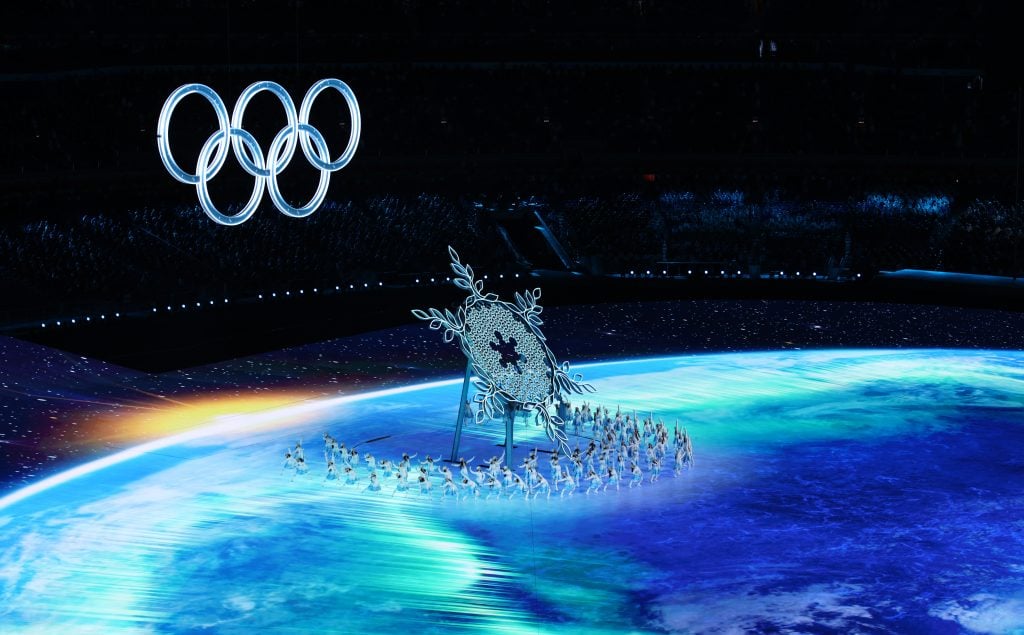

The eagerly awaited torch lighting at the opening ceremonies for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games was a rather staid affair.

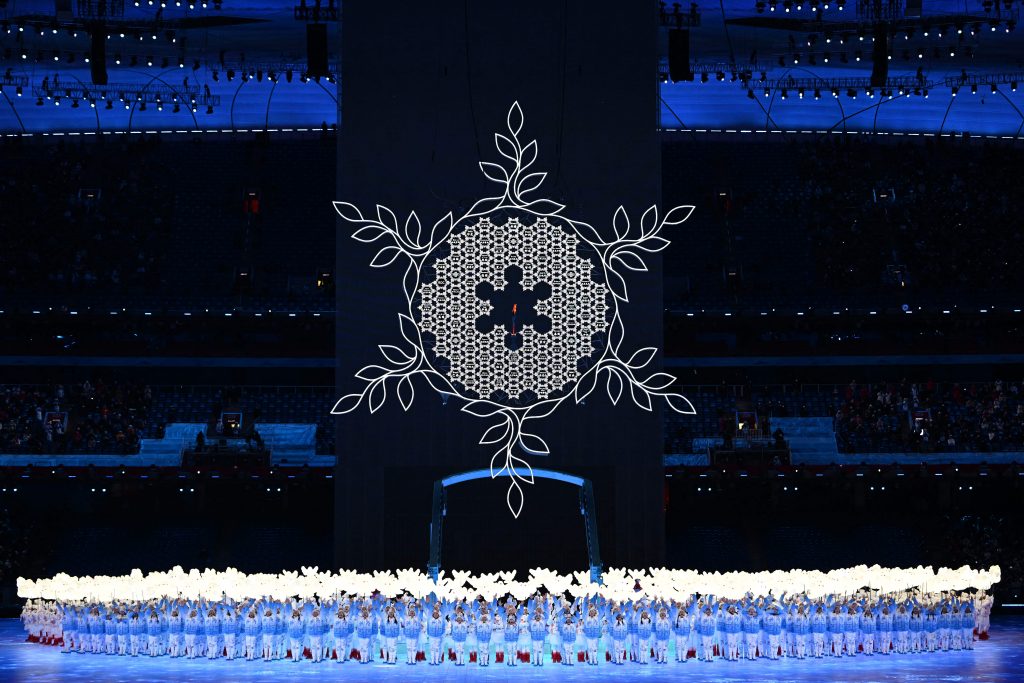

The torchbearers simply placed the flame in the center of a massive LED snowflake, which then ascended above the stadium.

There was no epic eruption of fire, and the flame was quickly lost to view once cameras panned out to the ensuing fireworks show.

In comparison, the Olympic flame at the 2016 Rio games was set amid a glittering kinetic sculpture of metal and glass by artist Anthony Howe. Last year, the 2020 Tokyo Games opened in dramatic fashion with Japanese tennis champion Naomi Osaka ascending an enormous staircase towards a glowing white orb (designed by Canadian architect Oki Sato) that opened like a flower as the flame ignited.

The lack of drama to kick off the 2022 competition was all the more disappointing considering the over-the-top spectacle of the Summer Beijing games, with its unforgettable display of 2,008 drummers playing in perfect unison.

Filmmaker Zhang Yimou, who also helmed the earlier memorable affair, directed this year’s much shorter festivities—about 100 minutes, compared to four hours in 2008.

A giant snowflake sculpture with the Olympic flame at its center during the opening ceremony of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games, at the National Stadium, known as the Bird’s Nest, in Beijing, on February 4, 2022. Photo by Manan Vatsyayana/AFP via Getty Images.

Due to pandemic restrictions, the cast was trimmed from 15,000 to just 3,000, with most of the visuals coming from a 38,000-square-foot LED screen on the floor of the stadium, itself designed in 2008 by Herzog and de Meuron and Ai Weiwei. (Ai was later imprisoned by the Chinese government for 81 days, and has been outspoken in his criticism of these games.)

The giant illuminated snowflake, a recurring symbol inspired by a Li Bai poem, was made of 91 smaller snowflakes representing each delegation to the games.

During the Parade of Nations, these light-up snowflakes served as placards announcing each country’s entry into the stadium. The six legs of each smaller snowflake were shaped like Chinese knots, traditional decorative artworks, while the larger sculpture featured olive branches in a symbol of peace.

Chinese torchbearer athletes Dinigeer Yilamujian and Zhao Jiawen hold the Olympic flame during the opening ceremony of the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympic Games. Photo by Ben Stansall/AFP via Getty Images.

The cauldron lighting was “unprecedented” in the modern Olympic games, Zhang told Variety ahead of the ceremony. “We’ve significantly reduced the number of performers, and [instead] use technology to make [the stage] less crowded, but not empty. Technology and new concepts will make it feel full, ethereal and romantic.”

Yet perhaps the most notable aspect of the ceremony was how it was completed: by Nordic combined athlete Zhao Jiawen and cross-country skier Dinigeer Yilamujiang, reportedly of Uyghur heritage, taking the flame together from six retired Chinese athletes.

The move was an apparent response to reports that China is engaging in human rights violations—if not outright genocide—against the Uyghur population. (The U.S. is among nations that have declared a diplomatic boycott of these games.)

The inspiration behind the Olympic Torch for Beijing 2022, designed by Li Jianye. Courtesy of the Beijing 2022 Organizing Committee.

The torch used in the ceremony is called Flying, and was designed by Li Jianye in the shape of a fallen leaf. The red and silver colors are meant to evoke fire and ice, as well as the 2008 cauldron. It features a snowflake motif (a tie-in to this year’s flame display) and a curving red line representing both the games’ ski course, and the Great Wall of China.

The nation’s most famous cultural heritage site is also being honored at Genting Snow Park in Zhangjiakou, China, where the course for snowboarding is shaped like the Great Wall. The design is both aesthetically pleasing and practical, as it shields riders from the wind.

Norwegian snowboarder Mons Roisland practices on the Great Wall of China-themed slopestyle snowboard course at Genting Snow Park in Zhangjiakou, during for the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympic Games. Photo by Xu Chang/Xinhua via Getty Images.

“The course is pretty amazing,” New Zealand snowboarder Zoi Sadowski-Synott, who won bronze medal at the 2018 Pyeongchang Games, told Reuters. “There’s an amazing piece of snow artwork of the Great Wall. I’ve never seen anything like it, they’ve really outdone themselves.”