Opinion

The Wacky History of Andy Warhol’s Anti-Nixon Campaign

THE DAILY PIC: There's a rich pedigree behind Kass's pro-Hillary portrait of Trump.

THE DAILY PIC: There's a rich pedigree behind Kass's pro-Hillary portrait of Trump.

Blake Gopnik

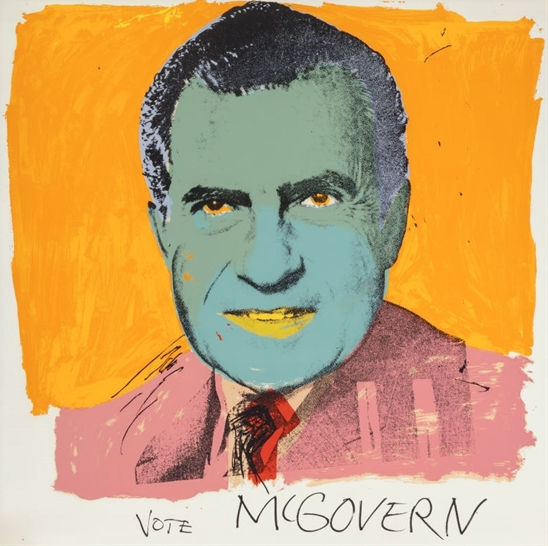

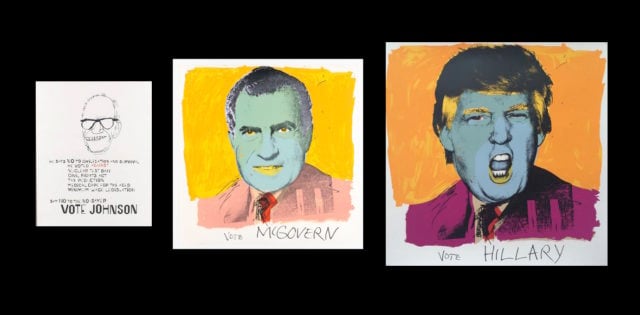

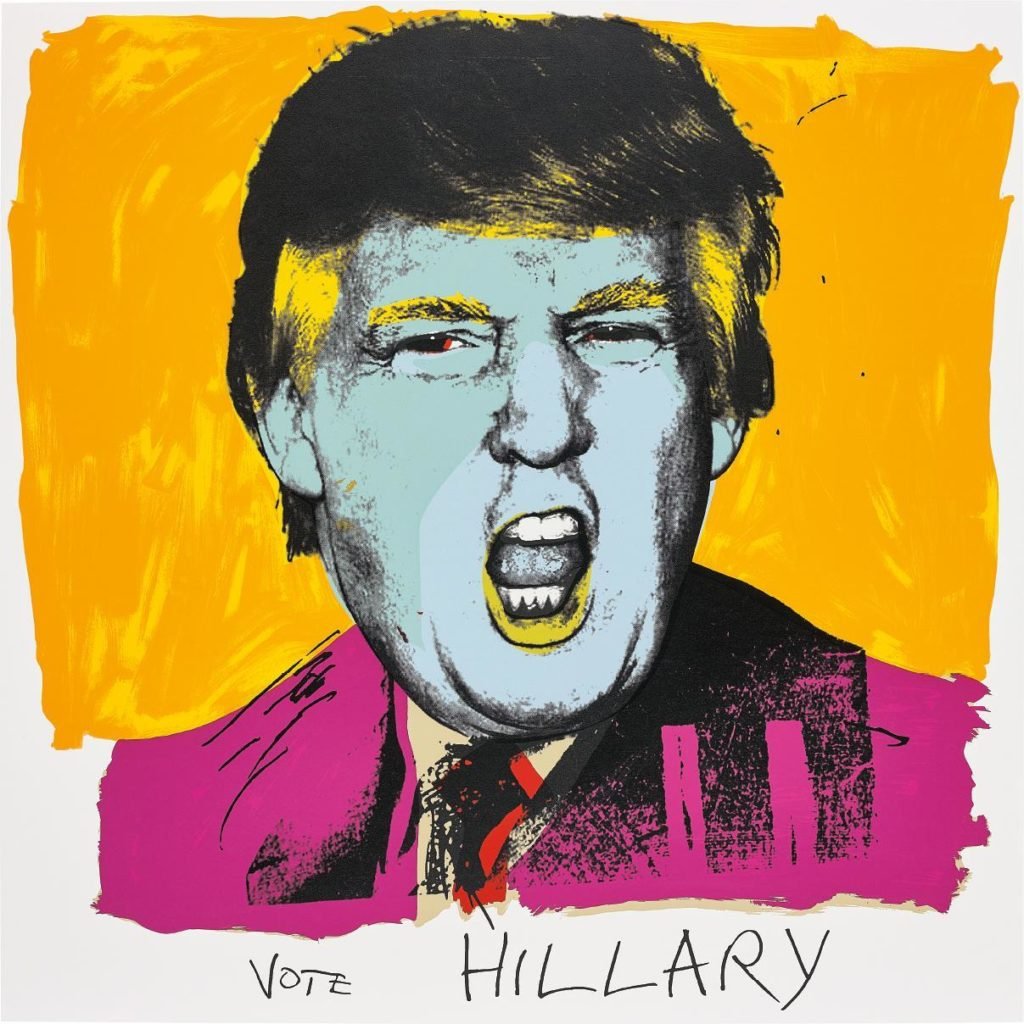

THE DAILY PIC (#1589): Deborah Kass’s pro-Hillary portrait of Donald Trump has been getting some attention lately, and Kass and her fans all know that it’s a deliberate appropriation from Andy Warhol’s pro-McGovern portrait of Nixon (above center).

But I wonder if Kass also knows that there’s another item in the same evolutionary series: A pro-Johnson portrait of his opponent Barry Goldwater, drawn in the run-up to the 1964 election by Ben Shahn, possibly the greatest single influence on Warhol’s pre-Pop work. I wrote about that pedigree in this column a year ago. (See below for that older text.)

Ben Shahn, Vote Johnson (1964); Andy Warhol, Vote McGovern (1972), ©the Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York; Deborah Kass, Vote Hillary (2016).

Warhol probably doesn’t strike most people as an engaged political figure, but from his student days on he was involved with left-wing ideas. Aside from trying to torpedo Nixon, he quietly supported any number of progressive causes; his archives are full of their thank-you notes.

Another thing that many people probably don’t quite realize: Despite his reputation as one of the great original makers in art, Warhol was at least as important as one of art’s great appropriators. He was a devoted follower (and collector) of Marcel Duchamp, past master of the borrowed image, and he happily lent a hand—and his silkscreens—to Sherry Levine, the younger appropriation-art pioneer.

Deborah Kass, Vote Hillary (2016). Courtesy of the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Warhol’s talents as a pictorial sponge and even thief are as important as any skills he had in making new imagery. Let’s not forget that almost all his signature Pop pieces—the Campbell’s Soups, the Marilyns, the Brillo Boxes, the Flowers—existed in another form first.

So when Kass riffs on Warhol, she isn’t only riffing on an image he produced; she’s riffing on his riffistry.

Here’s what I wrote last year about the Warhol/Shahn relationship:

THE DAILY PIC (#1304): This little-known print by Andy Warhol is now on view in the Whitney Museum’s giant re-do, at the foot of the High Line in Manhattan. Warhol made it in 1972, as a fundraising piece for Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern. He was capitalizing on the fact that many supporters would probably be pushing for the Democrat out of simple disgust with Nixon – Tricky Dick here presented more or less as the Wicked Witch of the West (who happens to have been a favorite of Andy’s).

But there’s one thing to note about Warhol’s strategy: He stole it, lock, stock and barrel, from a similar show-the-other-guy image done by Ben Shahn in 1964, supporting Lyndon Johnson against Barry Goldwater.

Now, in the context of Warhol, this doesn’t (quite) count as a shameful act: His entire career depended on his genius as a sponge, and people had known it for years – especially with regard to Shahn. The “blotted line” that defined Warhol’s commercial illustrations, in the 1950s, was built on an obvious imitation of the fractured mark-making that was already a trademark of Shahn, then one of America’s best-known artists. Warhol’s commercial clients have said that they thought of Andy as Shahn-on-the-cheap, and as Shahn without all the far-left baggage.

In the case of Warhol’s Nixon image, however, there’s more at stake. (There always is, with Warhol – that’s how he ended up being greater than Shahn.) For one thing, the theft must have been recognized as such by the kind of politically-informed artsies the print would have been targeted at. That means it wasn’t a theft, so much as a witty riff and homage – Shahn’s image, only eight years old, updated for a new age. The Warholian style of the 1972 image means that it acts as a youth-culture stamp of approval for McGovern.

Also, Warhol was so much more famous, by ‘72, than even Shahn had ever been that the piece comes to have three notable figures as its subject – McGovern, Nixon and Warhol – rather than simply the two in Shahn’s piece. One decade after the invention of Warhol’s silkscreen technique, every portrait that uses it is also, in some sense, a self-portrait of the artist. Not-Nixon is Warhol, as much as it’s McGovern.

Vote Democratic, and you’re voting Warholian. (No wonder Nixon won.)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.