Op-Ed

In the Past Two Years, Museums Have Finally Started Hiring Black Women for Top Jobs. Why Are So Many Already Leaving?

It takes ongoing institutional support to create true change.

It takes ongoing institutional support to create true change.

Lise Ragbir

I cheered when I read that Kimberly Drew would take up the role of associate director at Pace Gallery. I also cheered when Naomi Beckwith was appointed deputy director of the Guggenheim, when Maria Rosario Jackson took the helm of the NEA, when Vivian Crockett signed on as curator at the New Museum, and when Eunice Bélidor became the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts’s first Black curator in the institution’s 161 years.

With each headline I think, We’re finally being seen. But I’ve also learned that being seen and making change are two different things. Being seen can happen in a moment. Change, especially institutional change, takes time.

I recently texted a friend, another Black woman, to ask if she was still with the institution that hired her last year. She tapback’d “HAHA” before explaining, “Yes, I’m still there. It’s a good question though, because I’m constantly reconsidering my place there.”

Many of us, especially women, suffer from imposter syndrome. (Raises hand.) And it’s easy to question our role within an institution in the first year. I know, because I’ve worked with arts institutions for nearly two decades—in positions ranging from intern to director. From non-profits to commercial spaces to grant-making organizations to the academy, I’ve learned that, as with any relationship, the first year is about aligning strides and building trust. And the support of the people who hired you is a critical part of that alignment. Change-making is hard, even with the trust and support of your colleagues.

Contemporary Arts Museum Houston.

We all know that without support, change, and most everything else, is near impossible. So, when an institution proudly announces a hire, we hope it’s a vote of confidence. We hope those press releases with beautiful headshots mean they don’t just want to look like they’re changing—but that they’re really doing it, and further, that they trust this person to lead that change. Surely they understand, we think, that real change takes time and that new hires need more than six months to prove themselves.

Sadly, that’s not always the case.

The Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, the Hammond House Museum in Atlanta, and the MacLaren Art Center in Canada all placed Black women in leadership positions in the past year and a half. None of those women held their positions for longer than six months.

In contrast to their splashy arrivals, these departures were mostly quiet. Gugulethu Moyo’s short tenure at Tucson’s Jewish History Museum was very public. One headline read: “Black Jewish History Museum Director, Tasked With Both Curating and Cleaning Toilets, Forced Out After Getting ‘Political.’” Six months after the museum’s board unanimously selected Moyo to lead the museum, she resigned. She said, “I was not treated as a leader.”

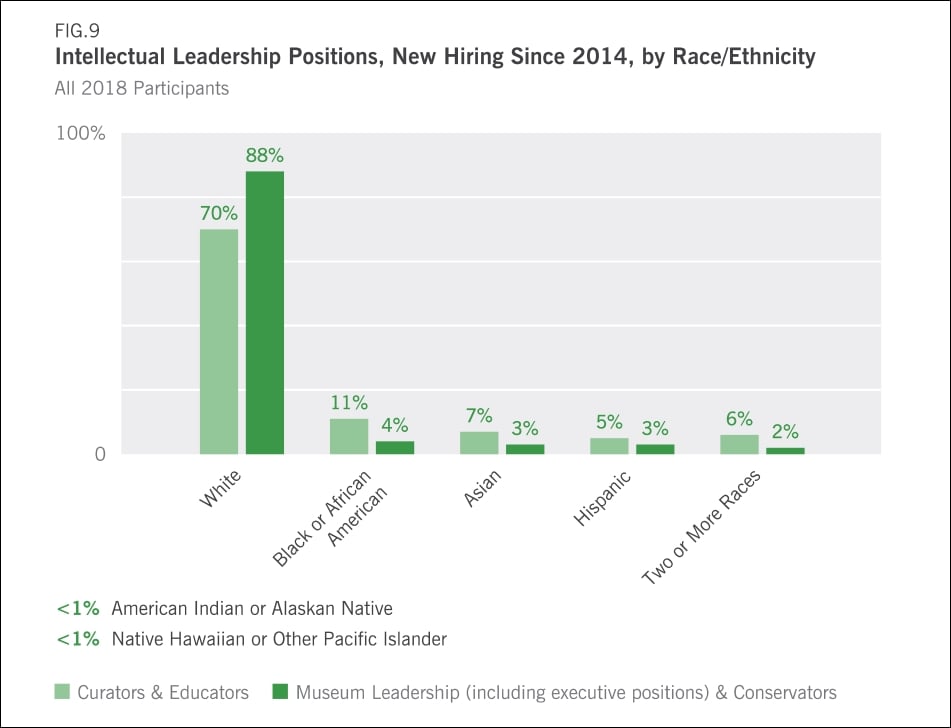

We know that Black people have historically been, and continue to be, underrepresented in leadership positions in the arts and museum fields. According to a 2015 report by the Mellon Foundation, only 4 percent of positions that impact the institution’s cultural direction are held by Black people. The report was so grim, a 2018 followup was commissioned—revealing that after three years, the number of Black people in “intellectual leadership” positions rose by 11 percent.

In a statement on the findings, Mariët Westermann, then Mellon’s executive vice president for programs and research said, “While trends in recent hiring are encouraging, certain parts of the museum appear not as quick to change, especially the most senior leadership positions.”

Charts from Art Museum Staff Demographic Survey 2018.

Since then, sweeping calls for social justice and pandemic shutdowns have further impacted the field. Institutions were forced to shutter their spaces and reevaluate their priorities. One response seems to have been a slew of headline-making new hires. People of color, especially Black women, are being invited into the halls of power. But, as we know, with great privilege comes great responsibility. And decades of exclusionary practices cannot be changed overnight. As one woman told me: “There have been no hires of people of color since I was hired. And when racial issues arise, I’m the one who’s supposed to find solutions.”

Furthermore, the swift departures of these women in leadership positions have generally been swept under the proverbial rug, where these women quietly navigate the complexities of their short tenures. Anyone who has built a career in a field where references and confidentiality matter, or has experienced racism and/or sexism on the job, can understand how these departures would remain out of the spotlight. Anyone who has ever spoken out and not been believed, or ostracized, or villainized knows that speaking out is not always all it’s cracked up to be—and for some, it can pile on to already-there vulnerabilities. A whistleblower is often only a whisper away from “madman,” or “angry Black woman.” This is why allyship is a critical part of the change we seek.

I get it. These are unprecedented times. Pandemics. The Great Resignation. The Great Renegotiation. Burnout. More choices. Less choices. Priorities are shifting as many of us reexamine our quality of life. In some ways, the “human” part of “human resources,” is being tested like never before. So, shouldn’t human resource protocols encourage support, instead of departures, like never before?

I understand that exciting hires far outweigh the regrettable departures. I understand that we’ve come a long way, and I know we have a long way to go. And while I’ll continue to cheer the hires that make me say “Yes! We’re doing it!”, I also hope these changes run deeper than a headline.