Opinion

Champions of Chicano Art Need to Face Reality: A Response to Cheech Marin’s New Art Center

Karen Mary Davalos, a professor of Chicano and Latino Studies, explains why the time is now to support Chicano Art.

Karen Mary Davalos, a professor of Chicano and Latino Studies, explains why the time is now to support Chicano Art.

Karen Mary Davalos

For decades, comedian Cheech Marin has been finding ways to bring attention to Chicano art. The avid art collector has produced several traveling exhibitions from his collection, served as an ambassador to mainstream museums, and hosted private events to introduce emerging artists to his network. And while critics may turn up their noses at shows based on his collection of Chicano art, they cannot so easily write off his latest venture to open a Center for Chicano Art in Riverside, California. After all, Eli Broad has received nothing but praise for doing exactly the same thing. The Broad in downtown Los Angeles is still considered the icing on the LA art-scene cake.

Cheech Marin is truly an advocate for Chicano art, but lost in the celebratory coverage of his vision for an art center in Riverside is the fragile infrastructure that endorses Chicano art. In Southern California, the region with the nation’s largest population of Mexican Americans, institutional support for Chicano art is thin. This might be the reason Cheech has copied Eli Broad’s strategy—one with centuries of tradition, too. If you don’t like how mainstream museums are neglecting important collections, then build your own.

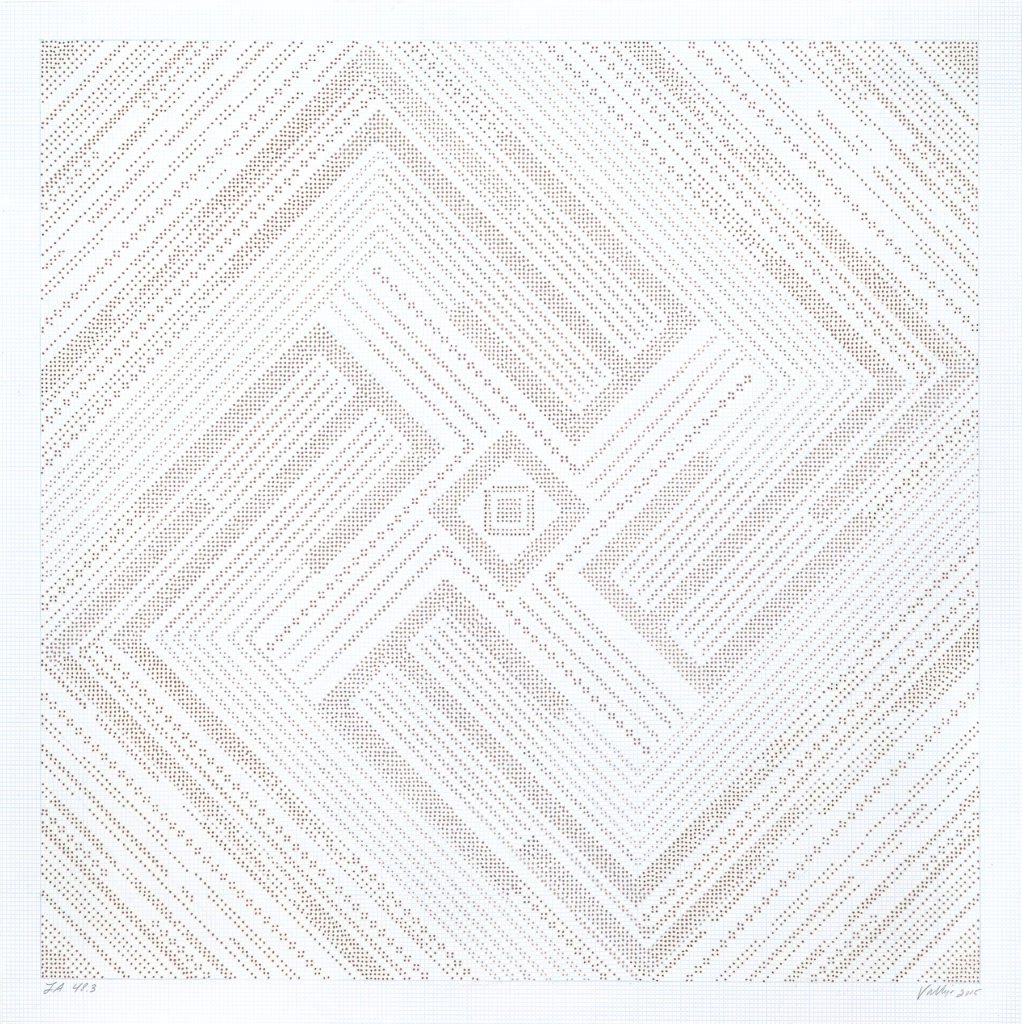

Linda Vallejo, Standing Spirits, 1999. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

And he is right. None of the major museums in the region have a permanent collection policy for preserving Chicano art. None permanently display the artwork, and none of them have employed a full-time expert on Chicano art. Following the national trend, you will only find Chicano art specialists in the education or public programs departments, and not in curatorial positions, where they might shape the interpretation and presentation of these museums’ collections.

Without systematic stewardship, what will happen to the masterpieces created by Chicano artists? Will they continue to linger in basements and under beds, damaged by dust, mold, and critters as UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center reported in 2003?

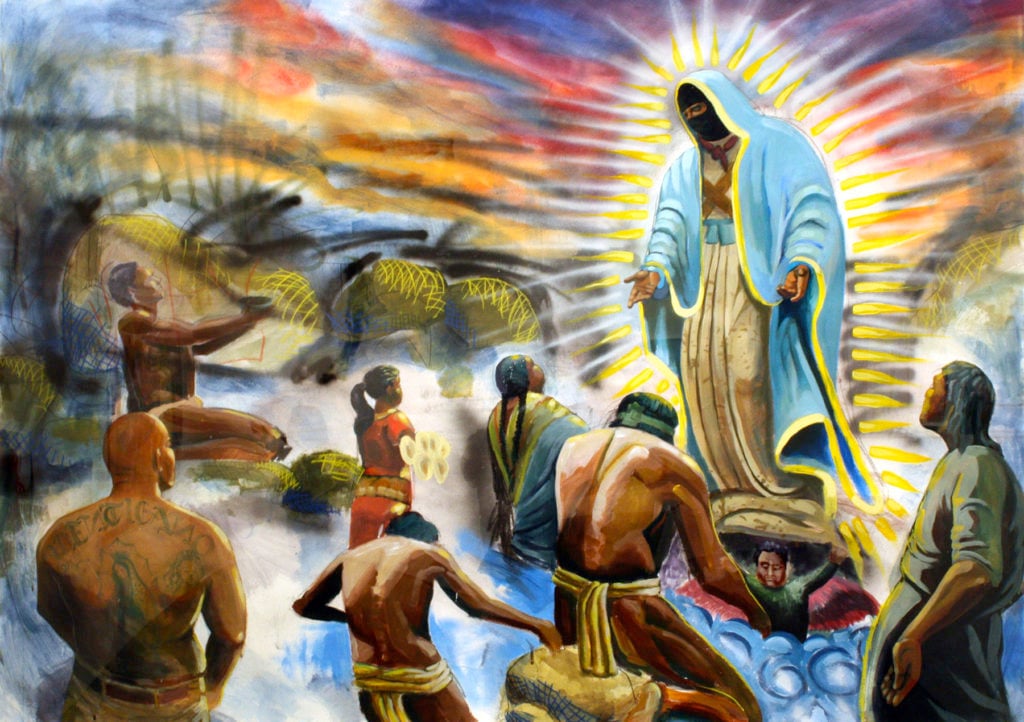

Pablo Andrés Cristi, If La Virgen Returned (2009). Image courtesy Riverside Art Museum, collection of Cheech Marin.

We know what happened to Chicano murals in Los Angeles. Between 2002 and 2013, the city banned all murals, even those commissioned on private property, to avoid legal challenges from corporations claiming that massive multistory advertisements were protected by free speech. The mural moratorium prevented artists and private owners from creating murals throughout the city. We lost the title of mural capital of the world to Philadelphia, because of this decade-long mural moratorium. Several non-profit arts organizations have worked to preserve the murals that enliven communities throughout the southland. But arts institutions, such as SPARC (Social and Public Art Resource Center), carry this burden for all of us, asking private and public funders for support, while also trying to produce new public works of art.

East Los Streetscapers, Gateway to Manifest Destiny, 1982. Photo © Grace Lane Gallery.

Cheech Marin is among a handful of private collectors acquiring and protecting Chicano art. The celebrity owns the most extensive collection of paintings (about 700). A scholar in the Midwest has the largest collection of works on paper (over 10,000), and a businessman in Texas has amassed over 2,000 paintings, prints, sculpture, and drawings. Luckily, they all allow their private collections to tour the country, but this is no way to preserve the heritage of our nation, let alone inspire future generations.

Granted, Southern California witnessed an unprecedented number of Chicano art exhibitions at major institutions in 2011. As part of the Getty Foundation’s inaugural Pacific Standard Time, Art in LA, 1945-1980, six Chicano art exhibitions premiered that fall. At least nine more Chicano art exhibitions are planned for the latest installment of Pacific Standard Time, called “LA/LA,” standing for Latin American and Los Angeles. One will be a solo exhibition of Carlos Almaraz at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, August 6–December 3, 2017.

Carlos Almaraz, Night Magic (Blue Jester),1988. Courtesy Smithsonian American Art Museum. © 1988 Carlos Almaraz.

Nevertheless, the Getty’s economic and arts stimulus package cannot alone fix the lack of consideration that Chicano art faces. For example, Carlos Almaraz’s art is part of LACMA’s permanent collection because the artist’s wife, Elsa Flores, donated his work to the museum after his death in 1989. No administrator or curator had the foresight to create a plan to purchase his art. Although this donation is ten times larger than all other collections of Chicano art in Southern California museums, the curator for the retrospective show, Howard Fox, had to make a public plea to private collectors in the pages of the Los Angeles Times. LACMA did not have enough art around which to build an exhibition.

Three other shows of Chicano art, all part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA, faced similar challenges, however these problems were forged by the Getty itself. The Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach, LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes in downtown Los Angeles, and UCLA—the home institution of one of the curators for “Home: So Different, So Appealing,” an exhibition of U.S. Latino and Latin American art, scheduled to open at LACMA—turned to crowdsourcing to raise funds for their catalogues, programming, and exhibition expenses.

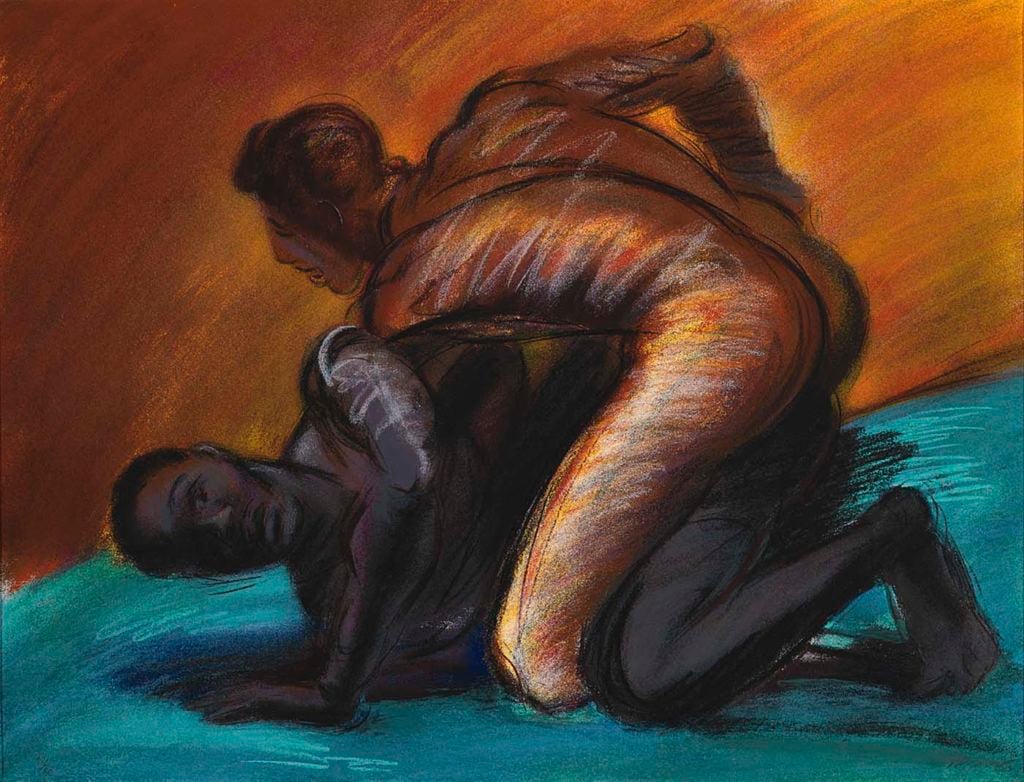

Carlos Almaraz, The Struggle of Mankind,1989. Courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum. © 1989 Carlos Almaraz Estate.

Why was the Getty not covering the full costs of mounting these exhibitions, an initiative reportedly focused on Latin American and US Latino art in dialog with Los Angeles? In fact, an analysis of the Getty grants awarded to support research and implementation of Chicano art exhibitions reveals that it represents approximately 17% of total funding. This cursory inclusion is likely a factor for Marin to build his own institution to advance Chicano art.

While I applaud Marin’s efforts, I also recognize that his art center will also need more than bricks and mortar. Chicano art requires more than just periodic initiatives, spectacular special programs, and neatly designed galleries. It demands long-term sustainable investment to create, preserve, and interpret the art of Mexican Americans. That investment needs to be widespread, fair, and equitable, especially for those arts organizations that have made Chicano and Chicana art central to their DNA for over four decades, since the onset of the Chicano Movement.

Wenceslao Quiroz, Pallet Pickup on 6th Street Bridge, 2013. Courtesy of Riverside Art Museum, collection of Cheech Marin.

To become the national leader in the conservation and support of Chicano art, Southern California necessitates an infrastructure that safeguards its art for generations to come. I envision that each arts organization participating in the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative would have a full-time staff devoted to the scholarship and curatorial study of Chicano art. Public and private foundations, corporations, and philanthropists should shift their focus to those arts institutions that have been serving Chicano residents and producing art for decades. Funders like the Getty would require mainstream arts museums to operate as collaborators with Chicano arts organizations from the inception of their new, sparkly and important programs and exhibitions. Universities, especially those educating students of art and cultural history, need professors, research centers, and programs devoted to Chicano art, now more than ever.

Linda Vallejo, LA 48.3%, 2015. Courtesy BG Gallery, Santa Monica.

Karen Mary Davalos is a professor of Chicano and Latino Studies at the University of Minnesota and the President of the Board of Self Help Graphics & Art in Boyle Heights, California. She is an independent curator and an author of three books about Chicana/o art. She recently launched a major project, “Xican@ Art since 1848,” which will result in the first comprehensive, multi-volume book and digital archive on Mexican American art in the United States since the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.