Opinion

Why the Columbus Monument Should Be Seen as a Monument to the Construction of Whiteness in the United States

From Benjamin Harrison through Richard Nixon and beyond, appeal to the symbolism of Columbus has had cynical motives.

From Benjamin Harrison through Richard Nixon and beyond, appeal to the symbolism of Columbus has had cynical motives.

Ben Davis

Christopher Columbus is coming down across the country. About time, too.

Protesters are decapitating, toppling, or throwing Columbus statues into the water across the country this week. In the face of renewed calls to do something about Gaetano Russo’s 1892 statue of Columbus in Columbus Circle, the NYPD is now out guarding it, and Governor Andrew Cuomo spoke out in its defense on Thursday.

“I understand the feelings about Christopher Columbus and some of his acts, which nobody would support,” Cuomo said Thursday on a briefing. “But the statue has come to represent and signify appreciation for the Italian-American contribution to New York.”

It’s worth specifying that by “some of his acts,” we are talking about child sex slavery, systematic torture, and mass murder for the good of greed and empire. As for Columbus’s value as a larger cultural icon, his symbolism to Italian-Americans must be weighed against his symbolism to indigenous peoples. Any honest accounting of the real historical facts must see the epoch he opened up as one of genocide and suffering.

But I feel I am being redundant.

Two people hold up flags, noting the names of Native American people who have been killed, on the spot where a statue of Christopher Columbus stood on the grounds of the State Capitol on June 10, 2020 in St Paul, Minnesota. Photo by Stephen Maturen/Getty Images.

Certainly, I was taught the cheerful folklore about the voyage of the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria as a kid, and when I first encountered the darker side of Columbus in Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States, it still felt like samizdat. But there have been decades of Native-led activism and by now a much broader public is likely to be aware that the real Columbus was more devil than saint. Columbus statues only became a target so quickly because the sense that his myth is past its sell-by date is so widespread.

In the wake of the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, New York City ordered an audit of its monuments. In the end, the commission decided to remove only the monument to J. Marion Sims, once remembered for his contribution to gynecology, now infamous for having experimented on enslaved Black women. Cuomo then had the Christopher Columbus statue designated a national landmark in late 2018 to avoid any further attempts to bring it down.

Richard Alba, a professor of sociology at the CUNY Graduate Center who was on the special commission that reviewed controversial monuments, explained to ABC News why the Columbus Circle monument wasn’t considered for relocation or removal: “The history of that statue is different from the Confederate statues of the South, which were put up to symbolize the triumph of whites over blacks in the South.”

This is what I want to add here: they are not so different.

After the Unite the Right rally, as Charlottesville’s infamous Robert E. Lee statue was under siege, I tried to educate myself about the history of Confederate monuments. In fact, these went up not right after the Civil War, but many decades after, after the radical experiments of Reconstruction had been betrayed and put down. The mythology of the Old South was, scholars have emphasized, a later invention: “Only in the 1890s did the Confederacy become an emotional symbol,” Karen E. Fields and Barbara J. Fields write in Racecraft.

In the era when the reconsolidation of racist and extremely unequal post-Reconstruction rule in the South butted up against the explosive cross-race foment of the Southern Populist movement, Confederate myth-making enforced white supremacy over the Black population. But the romantic imagery of the Lost Cause also served a complementary function in constructing a mythological bond between poor Southern whites and their bosses: “If the faithful slave was central to the mythic past that justified the Jim Crow present, then the faithful Confederate soldier might encourage obedient behavior among the working classes of the New South,” as one paper puts it.

The context for the Christopher Columbus memorials like Russo’s 1892 sculpture is, clearly, something else altogether: the floods of immigration that transformed the surging industrial North, particularly in the latter part of the 19th century. Italian immigrants faced terrible discrimination in the United States. Like the Irish, they were demonized as inherently out of place in Protestant America, shifty and loyal to Rome because of their Catholicism. They were poor and crowded into ghettos and blamed for lowering wages and for crime.

And so a movement among Italian-Americans looked to Columbus as a legitimating figure to invoke. Who could be more “American” than the person said to have discovered America (never mind that Columbus’s life far predates any consciousness of a modern Italian nation)? And wasn’t Columbus’s Catholicism, then, just as organic a part of the American story as the Pilgrims’ Calvinism?

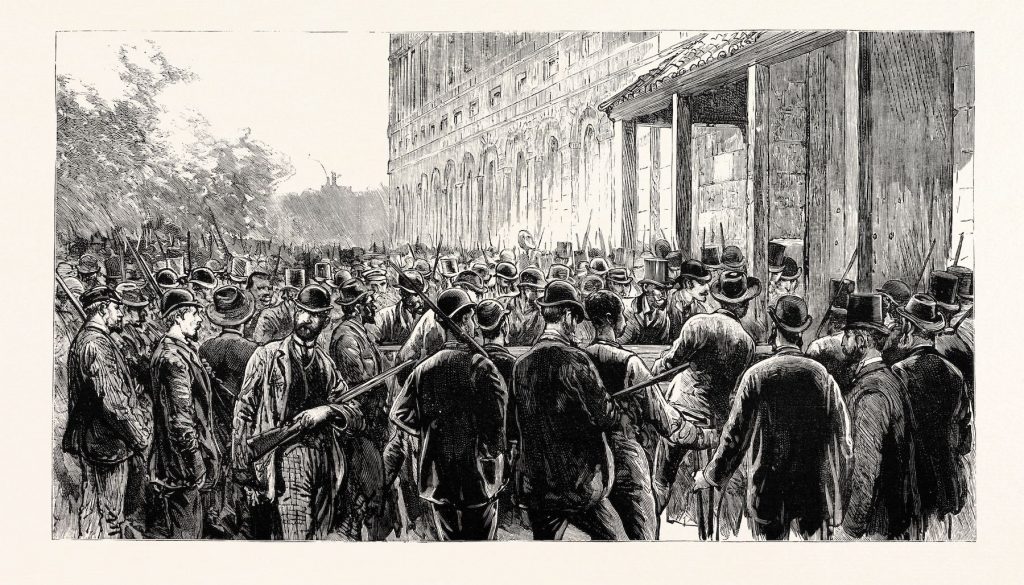

Illustration of the New Orleans lynch mob that killed 11 Italian-Americans on March 14, 1891. Photo by Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

On March 14, 1891, eleven Italians were torn apart by a white mob in New Orleans—one of the largest lynchings in US history. In response to the shocking violence, the New York Times cheered the anti-immigrant pogrom on, referring to Sicilian immigrants as “a pest without mitigations.” The Italian government broke off diplomatic ties with the US. Tension flared between president and congress over how to resolve the spat.

Amid attempts to manage the fallout, an intensified emphasis on the mythic figure of Columbus could play a role. The explorer offered a symbol of acceptance to the Italian community that was also comfortingly non-alien to the white establishment (the father of US letters, Washington Irving, had codified the legend of Columbus as American hero in his 1828 A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus).

Announced in 1892, the precursor of Columbus Day, “Discovery Day,” also happened to come in an election year. It has been seen as a calculated gambit of embattled Democrat incumbent Benjamin Harrison, looking to symbolic theater to court the immigrant vote in his losing election showdown with Grover Cleveland. (For similar reasons, the Republican Platform symbolically endorsed the cause of Irish home rule.)

Later, Franklin Roosevelt would proclaim “Columbus Day” a day of observance and national pride in 1934, with very similar aims. The idea of a national recognition of Columbus Day was an initiative of the Knights of Columbus and one Generoso Pope, a Tammany Hall kingmaker and key to delivering Roosevelt the Italian vote in New York. And so Roosevelt dutifully passed it.

Italian-American newspaper publisher Generoso Pope, in business suit at center of group, after having decorated the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier in Rome, Italy. Image courtesy Getty Images.

As it happens, Pope’s Italian nationalism also led him to be an ardent supporter of Mussolini, which then complicated Roosevelt’s turn against the Axis in WWII. Pope helped bankroll Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia and used his power to lobby Roosevelt to remain neutral on the matter. Pro-fascist Italians in the US hailed Mussolini as a “modern Columbus,” even as street demonstrations of Italian jingoism inflamed racial tensions, with Black communities rightly viewing the invasion as fresh evidence of Europe’s history of domination of African peoples. Columbus Day in New York through the ’30s was very much a pro-Mussolini event.

In 1940, with Italian-American sentiment taking extreme umbrage at Roosevelt’s anti-fascist overtures, the administration looked to his Columbus Day speech to lure them back: “Would it not be helpful if an indirect reference was made to the fact that Columbus was an Italian?” Roosevelt’s administrative assistant wrote him. “Reports are that some of the Italian groups in New York are still shakey [sic].”

Columbus Day as an actual federal holiday on the second Monday of October is quite young—it only dates to 1972. And there, too, you have to see its consolidation in terms of political fortunes: Richard Nixon’s attempt to construct a new constituency for the Republican party. With the Jewish and Black votes firmly in the Democratic camp, his advisers told him that working class “white ethnics” could be won.

Patrick J. Buchanan, when he was executive assistant to President-elect Nixon. Image courtesy Getty Images.

Specifically, Pat Buchanan, the proto-Trump who would coin the “culture wars” paradigm in the ’90s, had advised that Nixon specifically target “union halls, Columbus Day activities, Knights of Columbus meetings, etc.” Already in a 1969 proclamation, Nixon had taken it upon himself to affirm gallantly, “We remember also that Columbus was a man of Italy, a noble example for the many other men of Italy who have come to our country and to so many other lands of the new world.”

As Buchanan recalled fondly later, “Nixon often would talk about how the Italian-American vote was beginning to move. We had wanted to appoint an Italian-American and a Southerner to the U.S. Supreme Court, partly with the idea of recognizing these folks and saying ‘you’re not outside the country club of America as far as we’re concerned.’”

When people talk, today, about the construction of whiteness, this is what they are talking about: this idea of gaining entry to the imaginary “country club of America.” Appealing to the whitewashed Columbus myth has been precisely a tool of this operation, yoking together Italian pride and an identification with defending the innocence of the American project—and that really is very similar to how the ennobled image of the Confederacy works, claiming to be just about “heritage” or “Southern pride” while skating over the actual racist histories its symbols contain.

Cuomo tells us we should turn our eyes from the actual, historical figures being memorialized to what the heroic image has meant to people. In this he unintentionally lays out exactly how whiteness works as an active ideology: a sense of cultural identity constructed at the price of willful blindness to the reality of others’ oppression.

New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo marches in the annual Columbus Day Parade on New York City’s Fifth Avenue on October 14, 2013 in New York City. Photo by Andrew H. Walker/Getty Images.

There are plenty of actually very great Italian-Americans to celebrate, and people absolutely ought to have dignified depictions of their heritage and history. If he had spine, Cuomo, as the country’s most prominent Italian-American politician, could play a constructive role here in pointing towards new icons in this pivotal time of reckoning, instead of standing by a homicidal Genoese adventurer as the indispensable symbol of pride.

And meanwhile, here’s something else that cannot be stressed enough: as Christopher Columbus towers over Central Park, the Lenape people who were here before European settlement have only scant representation in the city.

The Netherland Monument in Battery Park. Image courtesy New York Park Service.

In fact, to my knowledge, there are just two memorials that feature the Lenape, and both contain historical inaccuracies. Both speak of the “sale of Manahatta,” which Native activists call a myth. As David Penney, one of the curators of “Native New York,” told Smithsonian magazine, the monument in Battery Park also depicts the Lenape figure in the dress that is actually associated with Plains Indians.

That combination of absence and ignorance is the flip side of the bombast and feigned innocence of the Columbus myth. One way or another, the latter has to be taken off its pedestal so that the real history can be given its full dignity—which is, clearly, only the very beginning of justice anyway.