For decades—if not centuries—people on plantations in Congo and elsewhere have been deprived of culture and forced into unpaid labor. This violence has supported wealth and art in the Global North, and we need to turn that around.

We represent the Congolese Plantation Workers Art League. The wealth of our people is enormous. The artistic wealth of our community is enormous. And yet, the land is no longer ours, and despite many efforts, it is very, very hard to make a living. Since 2014, we have made a practice of buying back plantation land, hectare by hectare, using the proceeds of our art, and transforming it into ecological havens that will be secure for future generations.

In 2015, we organized a small conference with invitees from Kinshasa and the plantations to discuss the role art could play in getting back our land. One major inspiration was a lecture from Charles Sikitele, a professor at the University of Kinshasa. He drove the 335 miles from Kinshasa to the makeshift conference center we had built in Lusanga, the former capital of the Unilever plantation empire in Congo.

Sikitele told us of the revolt of the Pende in 1931, the last great armed rebellion against the colonial state before independence. It is safe to say that few curators or researchers previously visited, so we were hanging on his every word. As we would learn, the Pende rebellion fought against the recruitment of forced labor to work on the plantation in Lusanga.

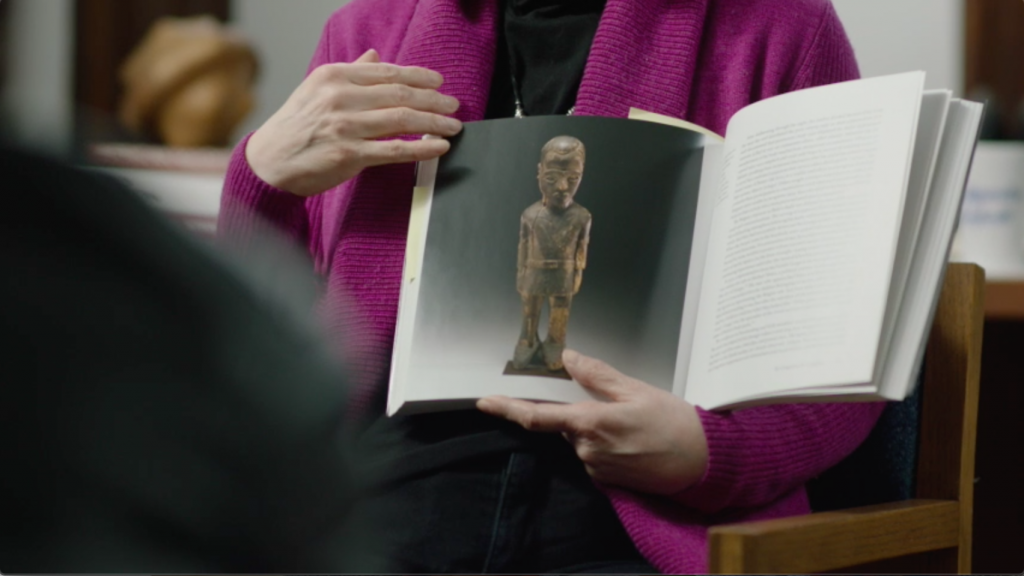

A figure representing Balot. Photo by Travis Fullerton, © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

During this revolt, the community carved a sculpture to protect their members against rape and other forms of colonial violence. This sculpture depicts the angry spirit of the beheaded Belgian officer Maximilien Balot, an agent who took women hostage to coerce the men to work for Huileries du Congo Belge, a subsidiary for the Lever Brother plantations (now Unilever) at Lusanga.

During the revolt, the community killed Balot and made the sculpture as a way to control his spirit and make it work to benefit the Pende people, rather than the colonial apparatus. Today, the sculpture is held at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, Virginia.

With the palm oil that was extracted from Lusanga and other plantations in Congo, Lever amassed profits that he used to finance museums, including the Lady Lever Gallery in Liverpool, as well as academic institutions, such as the Leverhulme Trust. Until as recently as 2012, Unilever funded the Unilever Series at Tate Modern.

“If it was not for plantations, you would not have all these beautiful art museums you see in Europe,” Simon Gikandi, author of Slavery and the Culture of Taste, told us in our documentary series Plantations and Museums. We know that Gikandi’s analysis is valid: Many of Europe’s key contemporary art museums, including the Tate galleries, the Stedelijk Museum, and the Ludwig Museum have been financed with profits extracted from forced labor on plantations.

We were born and we live and work on a plantation in Congo. It is safe to say that on Unilever’s former plantations the violence is still ongoing. Unilever sold their last plantations to an investment vehicle that pays taxes on the Cayman Islands, but profits still go to London.

Cedart Tamasala drawing Balot. CATPC, 2022.

We want to highlight a concern. Historically, museums and their audiences have gained from colonization while the people on the plantations gained nothing. Similarly, there is a real risk today that museums and their audiences gain from the process of decolonization, while the people on plantations still gain nothing from it.

Finally, artists and curators from these zones of extraction are being invited to play key roles in these museums and change the way history is told. But only a tiny percentage of the people who work on plantations will ever have the opportunity to visit any of these museums. We would need passports, visas, travel money, and free time, all of which are completely and structurally out of reach.

We wonder if decolonization risks further extracting value from us and the conditions we inhabit, if most of us can never, ever visit them? Should decolonization be limited to the people who have access to a middle-class or upper-class life in the old centers of empire? Shouldn’t it first and foremost play a positive role for the plantations and communities that involuntarily funded these same museums in the first place?

This is why we asked the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts for a loan of the Balot sculpture.

This was not a lighthearted request. The sculpture of Balot was made to protect against land theft, rape, and forced labor on the plantations where we still live. The violence against which the sculpture was made has not yet been resolved. On many former Unilever plantations, malnutrition is rampant. People organize marches, sit-ins, and protests to get their land back. Against all odds, people try to set up international support groups and file legal complaints against the spirit of imperialism and colonialism, often operating in regions without internet access or the means to travel even to Kinshasa.

A recent Human Rights Watch report indicates that men on these plantations earn $18 per month and women only $9. People are jailed, disappear, or are killed.

Matthieu Kasiama in conversation with Ariella Aïsha Azoulay. Still from “Plantations and Museums.” Human Activities, 2021.

Unilever has claimed it no longer has anything to do with these plantations. A spokesperson for the company recently told the New York Times: “Unilever has had no involvement in the D.R.C. plantations since selling them well over 10 years ago.”

But this is not really true. Where did the money from that sale go? Why did it not return to the community? And how could Unilever sell land that was not theirs in the first place? Why does the palm oil that is produced still go straight into Unilever-branded products?

And why does Tate Modern mount exhibitions on progressive issues while the women that toil on the lands that have historically funded it make $9 per month?

Meanwhile, the Balot sculpture, meant to protect us, is in the hands of the Virginia Museum and travels from one institution to the next. For example, it was recently exhibited at the Rietberg Museum in Zurich, where it was part of an exhibition called “Congo Fiction,” which aimed to “critically assess the repercussions of colonialism.” While we are happy that the sculpture can play such a role for audiences in Zurich, we also need it.

The Virginia Museum has, so far, denied and ignored our loan requests. We were told that we would need to try and meet its standard loan requirements. Luckily, we had already built a museum on the exhausted plantation land that we bought back with the proceeds of our art, and even put air conditioning in it. Nevertheless, the Virginia Museum did not want to seriously discuss a loan request.

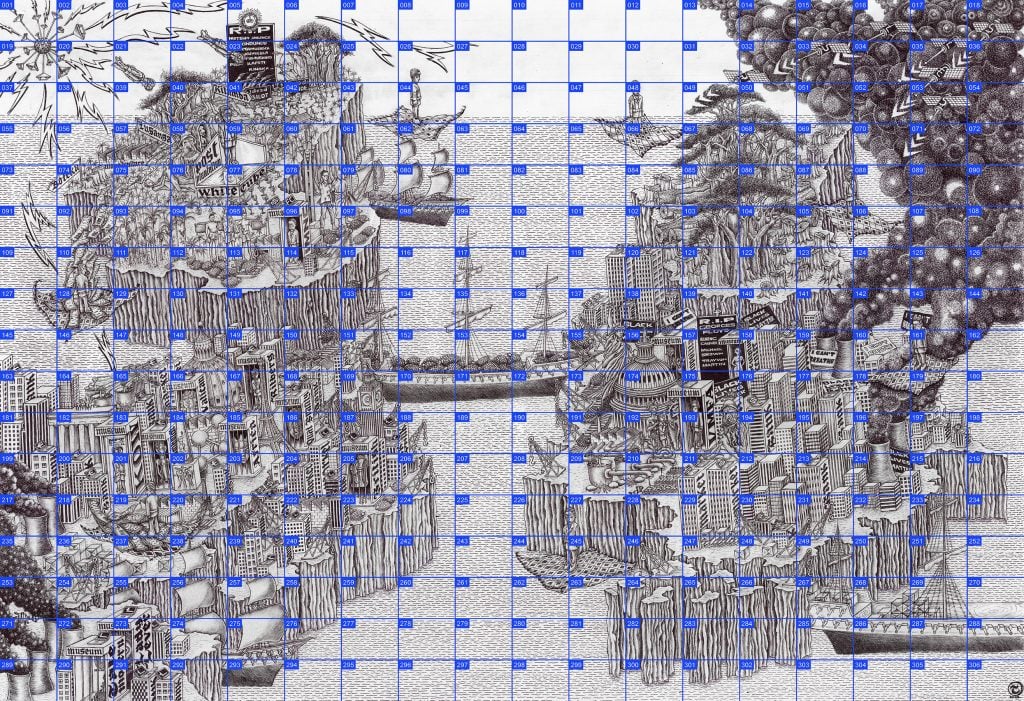

Video of 306 Balot NFTs, drawing by Cedart Tamasala / CATPC, 306 Balot NFTs, CATPC, 2022. Diviner’s Figure representing Belgian Colonial Officer, Maximilien Balot, 1931. Photos by Travis Fullerton © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

We made a drawing that maps out the global value chains of capital, commodities, and art, and depicts how the Balot sculpture was made to resist these unequal power relations. We downloaded the photographic reproductions of the sculpture from the Virginia Museum’s website (since this is the only way that we can have access to the sculpture) and later turned this reproduction into an NFT.

This new digital Balot now hovers over each of 306 fragments of the drawing, which maps out how we can control the powers of our lost art, and bypass institutions that were built on the exploitation of our labor and culture. We do not only claim the sculpture, we also claim the functions of the sculpture. Each purchase of one of the 306 NFTs buys and secures two and a half acres of exhausted plantation land, and helps to plant trees, offset carbon emissions, and reintroduce sustainable ways of governance, land use, and community building. Every purchase helps to further unleash the powers of the sculpture, and to re-fulfill its original functions: to protect our land and our people.

We are launching the NFT at the booth of our gallery, KOW, during Art Basel, and will hold talks on it at the fair, as well as at Documenta and Bundeskunsthalle Bonn. (The Basel event will also be livestreamed.) The NFTs will go on sale starting June 14 on our website and in a curated exhibition at JPG.space.

Major museums around the world have explored NFTs as a new way to capitalize on their existing collections. It is essential that deprived communities around the world act and reclaim their work before museums enter the next phase of extraction. This time, we take what is ours, and we share it with you, so that through the magic powers of the NFT, we can make our sculpture effective again—together.

Only if and when we get our land back can museums and audiences claim that they are decolonizing.