Opinion

3 Observations About Culture, Politics, and Social Media Radicalization in the Post-Trump Era

On digital populism and the influencer economy as a base of reaction.

On digital populism and the influencer economy as a base of reaction.

Ben Davis

“Everyone is making media at all times,” CNN reporter Elle Reeve reported of January 6 capital siege. “It’s crazy. It’s like, ‘Were you there if you didn’t livestream it?’ And they’re all hoping for that viral moment that will give them more clout on social media.”

The commitment to posting—even though this particular “viral moment” would ultimately provide authorities ways to track down the rioters—shows the degree to which politics has been recoded, in the Trump Galaxy Brain, as some kind of media project. “Politics is downstream from culture,” Andrew Breitbart, founder of the eponymous hard-right web outlet, once said.

Supporters of US President Donald Trump enter the Capitol as tear gas fills the corridor on January 6, 2021, in Washington, DC. (Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images.)

You don’t need an army of content-creating goons to have reactionary violence in the United States, of course. Reactionary mob violence, against the Indigenous and minorities, against the poor and the working class, has been an aspect of life in this country since before the creation of the Republic.

But what’s become apparent to me is that the dynamics of the networked DIY media economy are particularly catalytic to reaction, in ways I haven’t heard talked about. Not just because it is an efficient vehicle for spreading unvetted misinformation, though this is true. Nor because it creates filter bubbles or incentivizes mob mentality, though this is also true.

After four years, everyone should know that the deepest reservoir upon which the Trump base drew was not the “white working class,” but the “white petit bourgeoisie.” It’s a lot of small business owners.

The social media-ization of everything has added to that layer in a particular way. Social mobility may have declined in the United States, inequality has certainly soared, debt has ballooned, and physical infrastructure is crumbling—but media has gotten easier and easier to access and consume. This expanding cornucopia of tech and entertainment has served as a compensatory narrative of progress and advancement for an empire in decline. The future seems more and more constrained, materially, but, on the flip side, you are freer and freer to build your own virtual worlds and get lost in them.

Supporters of US President Donald Trump enter the US Capitol’s Rotunda on January 6, 2021, in Washington, DC. (Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images.)

The promise of viral fame has also provided a new-model rags-to-riches story to keep gas in the tank of America’s myth of itself as a middle-class nation of self-defined, self-made people, despite the pervasive sense of narrowing opportunity (even as Big Tech consolidated its monopolies). Whether you are an independent journalist looking to Substack, a sex worker on OnlyFans looking to survive the pandemic via a paying fanbase, or a QAnon wingnut decoding breadcrumbs and monetizing the resulting notoriety via T-shirts and Trump merch, the recent past has held out the individual internet hustle as the path to some form of stable autonomy.

In her great book, Labor in the Global Digital Economy, theorist Ursula Huws makes the point that online attention economies are built around “begging and bragging,” creating systematic psychic stresses. There is, she writes, “a cumulative battering of the ego that cannot be good for anyone’s self-respect even for those who (by definition a minority) emerge from the process as winners most of the time.”

After the Capitol assault, the New York Times wrote of participants that “a number of the feeds we reviewed suggested that those who’d made a sharp pivot to sharing misinformation were similar in their desire to cultivate a public persona.” The protesters the Times interviewed

shared an entrepreneurial streak. They expressed a desire for connection with others and sought to achieve it online. But their attempts at conventional influencing (via modeling, reality television, running a small business and sharing motivational content) brought only modest attention.

Until, that is, they found an audience in extreme conspiracies, and a plausible route to the micro-influencer fame that was otherwise out of reach. Jake Angeli, the “QAnon Shaman” who became the face of the Capitol attack, is similarly a failed actor and web spirituality entrepreneur. Scotty the Kid, who single-handedly built last year’s “Save the Children” rallies, is a failed model and rapper (specifically rapping about BitCoin.)

The squeezed small-business-owner class has been, classically, considered the popular base for fascism. Official ideology privileges and glamorizes the dream of economic independence, yet small proprietors are slammed by competition, atomized, and relatively powerless. The networked web economy specifically holds out a dream of glamorous independence and celebrity inflated way beyond its ability to deliver to large numbers of people, creating a substantial and volatile base of thwarted small-media entrepreneurs looking for salvation.

This idea of digital media’s role in the fix we are in may make it seem that the unprecedented, coordinated action by Amazon, Google, Facebook, Twitter, Stripe, and more to deplatform both Trump and his more extreme fans in the last weeks can only be a positive development.

In the wake of the bans, everyone is now waiting to see what effects they might have beyond serving as a kind of temporary emergency brake that has been pulled.

Supporters of US President Donald Trump enter the US Capitol’s Rotunda on January 6, 2021, in Washington, DC. (Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images.)

But, actually, most experts already agree what will happen.

“Bottom line is that de-platforming, especially at the scale that occurred last week, rapidly curbs momentum and ability to reach new audiences,” Graham Brookie of the Digital Forensic Research Lab told the Washington Post. “That said, it also has the tendency to harden the views of those already engaged in the spread of that type of false information.”

And those who are “already engaged,” keep in mind, are literally millions of people at this point. For those committed to sharing “Stop the Steal” memes, the coordinated action of Big Tech was further evidence of a diabolical scheme against them and against America—which is the very sense that created the conditions of reaction in the first place. Way back when Trump was first running in 2016, RAND found that how you answered the question “do you feel voiceless?” was the best predictor of his support among Republicans—better than age, race, college attainment, income, or attitudes towards immigrants or Muslims.

So, peace in the information sphere is bought at the price of further extremism, probably on a large scale.

Make no mistake, the loss of internet platforms is a huge blow for the right-wing culture warriors and internet conspiracy addicts, disorganizing, demoralizing, and dispossessing them. But there were, after all, much more sinister groups in attendance at the Capitol, dedicated to forms of militia action—IRL war instead of just the meme war. They’ve been prepping for years for a showdown and are actively looking to recruit.

It’s easy to imagine that, in turning off the online attention spigot, you have not only radicalized a sense of grievance on the level of belief but also redirected a lot of thwarted energy towards groups more dedicated to the non-virtual world as the center of the action.

Marchers parade past an Apple Store in San Francisco, protesting Apple Inc’s profits held in tax exempt overseas accounts in San Francisco, California. (Photo by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images.)

On the other side of the radicalization funnel, Big Tech absolutely does have way too much control over people’s lives—that is hardly a sense that only ultra-reactionaries share. There is a huge, unfocused mass of anger at tech that goes beyond political affiliation. Just as vaccine skepticism that crosses class and demographic lines has been a conduit into broad right-wing growth during COVID, this general angst opens dangerous pathways of solidarity.

We risk allowing righteous resentment at tech—which is only going to grow as more and more as people see these platforms as the last avenue of social advancement—to be tangled up and channeled into the racist, xenophobic, chauvinistic narrative of those who are the most evident target of the ban and the loudest voices against it.

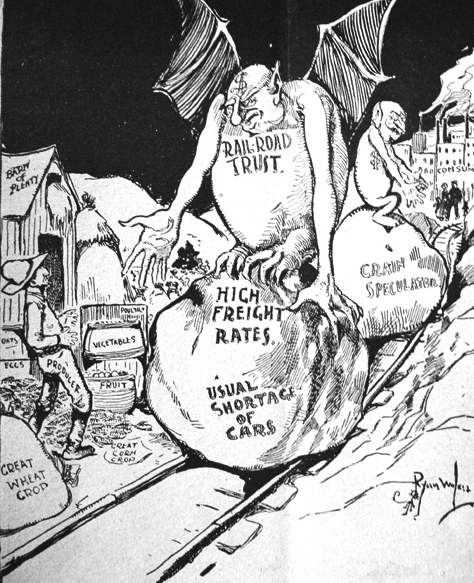

As Doug Henwood pointed out recently on the Behind the News podcast, the giants of Platform Capitalism today seem to be playing the same role in the public discourse as the railroads did in the late 19th century. Rail let small farmers get their goods to market, but also put them at the mercy of giant monopolies, stoking resentment. Now, social media behemoths control access to an audience, to visibility, to careers, to community, and so on, stoking resentment.

Ryan Walker, I Saw the Farmer and the Consumer and they who come between (1902).

It was in the broad revolt against the 19th-century rail monopolies that a term was born so potent that it endures in our political lexicon: Populism. It started out as a left-wing movement of radical democracy and redistribution of wealth, but has been channeled into right-wing strong-man “anti-elite” politics.

It matters a lot who captures the resentment generated by the real injustices of corporate domination over communication. It is very bad if people preaching an apocalyptic gospel are the ones who speak for it.

The Social Dilemma, last year’s blockbuster middlebrow “clickbait documentary” on the horrors of social media, contains a scene that is meant as a parable for what “social media is doing to the kids.” We are shown how phone-addled suburban teens are impelled by the sinister forces behind their screens to participate in a violent street protest, ending up in cuffs.

Press image from The Social Dilemma. (Image courtesy Netflix.)

The documentary, however, specifically refuses to show what the protest is all about. The problem at hand, the implication is, is neither left- nor right-wing extremism, just “extreme” opinions, generically. As if that term could be defined non-ideologically. (To symbolize the doc’s all-sided criticism, the signs you see at the protest tout the “Extreme Center”—probably not referring to Tariq Ali’s book of the same name critiquing technocratic liberalism’s role in paving the way for right-wing populism.)

I’m sympathetic to the idea that the profit models and practices of social media capital are having socially corrosive effects. But, in general, I think that the Trump-era pundit obsession with trying to combat the growing right at the level of technology has too often ended up being about looking for a technical fix for deep-seated social problems that have developed over years of social erosion—and this is dangerous.

An example of this perspective came in last year’s blockbuster “Rabbit Hole” podcast from the New York Times, which also set out to show how social media was a radicalization tool drawing people into conspiracies. The funny thing, however, was that its star example was Caleb Cain, described as a lonely young man, raised amid the decline of “postindustrial Appalachia,” failing to find a place for himself at college, then finding himself working aimlessly at a series of jobs—Dairy Queen, packing boxes at a furniture warehouse—without much of a sense of self-worth or future prospect.

From this life situation, this young man who started out as an Obama supporter discovers YouTube self-help content to fill his empty nights. This leads him to the men’s-rights content that leads him to the so-called “alt-light” content that leads him to dipping into the deeper waters of white nationalist content.

But by the time the Times talked to him, Cain had been both successfully radicalized and then deradicalized on YouTube. At some point, he found his way to videos where his alt-right heroes debated more left-wing ideas, put out by “BreadTube,” a group of self-consciously ideological “anarchists, democratic socialists, Marxists” consciously out to engage with reactionary online entrepreneurs and counter them on their own turf.

There is actually a kind of vindication of the importance of effective intellectual engagement in hearing how Cain is won away from the abyss by watching his favorite alt-right YouTube stars get owned by online lefties rolling up their digital sleeves to engage with their arguments and offer alternate explanations for the alienation and demoralization of his actual lived condition.

Caleb Cain, aka Faraday Speaks, analyzing a “Stop the Steal” rally on YouTube.

Nevertheless, podcast host Kevin Roose strangely takes a totally other lesson away from this parable. Towards the end of his profile, he reveals that Cain himself has started a YouTube channel, Faraday Speaks, where he tries to use his experience to reach people like him who might be attracted to the nastier ideas he had found himself dabbling in. Seems great to me! But here is how Roose engages with Cain:

I guess what I am sort of wondering is that it seems like, you know, you went pretty far down this alt-right rabbit hole. You didn’t get to the bottom maybe, but really close. And then you kind of found this path to this other part of YouTube that works kind of the same way, but with just a different ideology, and got sucked pretty far down into that by some of the same algorithms and the same forces that had pulled you into the alt-right. And I guess I’m wondering if that makes you feel like the problem is still that you kind of are in the rabbit hole, but you’re just in a different one. You’re still susceptible if the algorithm were to change in the future and lead you down some other path that was maybe more dangerous, that this could happen to you again.

You almost feel like Roose is about to say, “Have you instead considered… a subscription to the New York Times?”

Figures including artist Joshua Citarella have been, for years, repeating the message that the best alternative to the right-wing online content “funnel” is creating self-consciously leftwing alternatives. And yet, faced with his own reporting showing actual case-study evidence that left-wing ideas helped pull Caleb Cain away from alt-right ideas, and Cain’s effort now to do the same for others, Roose’s take on how to battle rising extremism is to tell him: stop doing that. (This Times Take, incidentally, very much fits Tariq Ali’s definition of an “extreme center” position.)

“Rabbit Hole” amounted to one long argument that YouTube, Facebook, et al. were derelict in their duties to stop society’s far-right drift, and should be more forceful moderators. Well, now this demand has been fulfilled in the most dramatic possible way, albeit after it was almost too late.

My fear is that this focus on moderating away the problem is ultimately a substitute for having an ideology, for doing something about it or for even having to think about “postindustrial Appalachia” anymore or address the real social conditions that are drawing people like Cain towards reaction.

I can’t say it’s not nice to have silence from Trump’s Twitter. But it’s worrisome to me to think that now that the Great Muting has happened, everyone—or everyone who’s comfortable enough to do so—is just going to go back to not thinking about all that he represented, as if the level of chaos and social fragmentation that we have lived through were something you could just hit mute on. As if the movie doesn’t still go on even though you can’t hear what’s going on.