Op-Ed

Hans Ulrich Obrist on a Radically Utopian Museum Model That Has Yet to Be Realized—and Why It’s Worth Pursuing

Obrist reflects on the legacy of the philosopher Édouard Glissant, whose unrealized ideas offer a path for the future.

Obrist reflects on the legacy of the philosopher Édouard Glissant, whose unrealized ideas offer a path for the future.

Hans Ulrich Obrist

Hans Ulrich Obrist met the Martinique-born philosopher, poet, and public intellectual Édouard Glissant in 1999; the encounter influenced the direction of Obrist’s work for years to come. Their relationship was driven by a spontaneity that enabled them to collaborate on a dozen projects, among them “Utopia Station” at the 2003 Venice Biennale. Co-curated by Obrist with Molly Nesbit, Rirkrit Tiravanija, with Elena Filipovic, the project was based on conversations with Glissant.

Before his death in 2011, Glissant sat for a total of nine interviews with Obrist, which, as part of the curator’s vast archive of 4,000 conversations, are now on display at the newly opened Luma Arles in the South of France. (The conversations are the subject of a forthcoming book, The Archipelago Conversations, by Edouard Glissant and Hans Ulrich Obrist, published by Isolarii.) The focus of this first presentation of Obrist’s archive is a collection of audio-visual material related to Glissant: videos of public and private interviews are screened on eight viewing stations, allowing visitors to listen to Glissant engage in dialogues, read his poetry, and form his thoughts while speaking. The presentation also features posters by contemporary artists who were either close to Glissant, or who feel connected to his thinking.

On the occasion of the exhibition, we’re publishing the below excerpt from Obrist’s essay on Glissant from the forthcoming Museum of the Future: Now What? (edited by Cristina Bechtler and Dora Imhof), in which the author reflects on the influence of the philosopher, and what his writings can teach us about the proper future of museums.

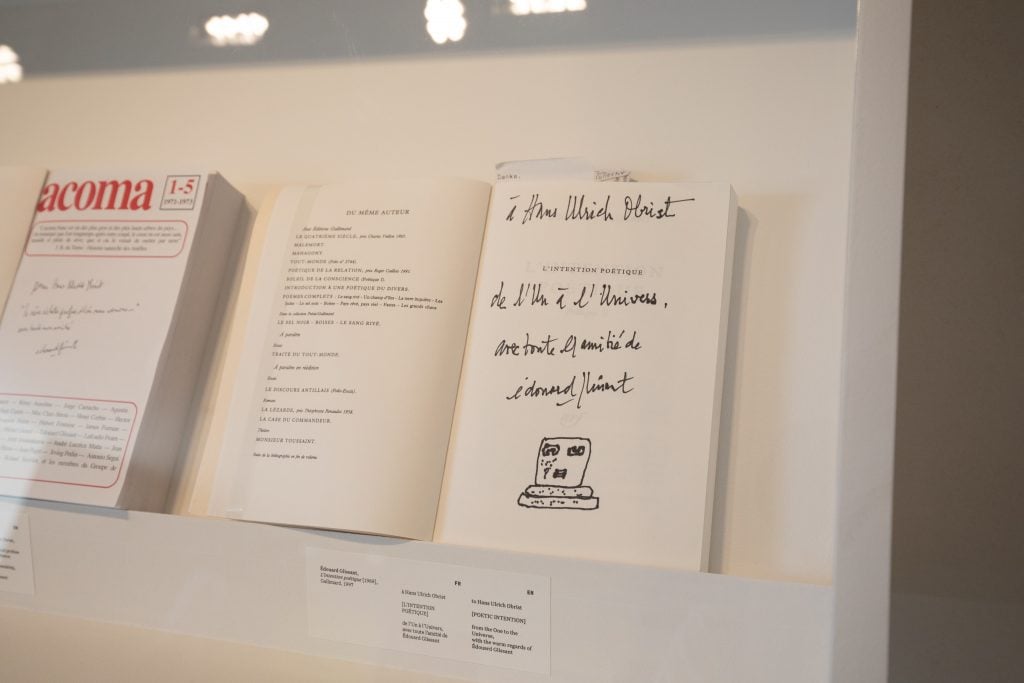

A note from Édouard Glissant to Hans Ulrich Obrist at the Luma Arles exhibition. Photo: Adrian Deweerdt.

What might constitute a museum for the 21st century? Looking for answers, I keep returning to an unrealized project of the late philosopher, public intellectual, and curator Édouard Glissant, who consistently told me that what matters is the production of reality.

Glissant—who was born in Sainte-Marie, Martinique in 1928, and was throughout his career an advocate for the island’s independence from France—imagined a museum for the Carribean island that would present the multiplicity of the art of both American continents. It was to span from the ancient Mayas to the present. He imagined the museum as an archipelago that would house a network of interrelationships. He wanted to create a museum that would not only point to urgent issues, but would also respond to them. He imagined it to be a “quivering” place that would transcend established systems of thought and look for the utopian point where all the world’s cultures could meet.

Glissant referred to his utopia as a “quivering” or “trembling” because it would transcend established systems of thought. “It must be said from the start that trembling is not uncertainty, and it is not Fear,” he wrote. “‘Trembling’ thought—and in my opinion every utopia passes through this kind of thought—is first of all the instinctive feeling that we must reject all categories of fixed thought and all categories of imperial thought.”

Glissant’s museum drew upon the history and landscape of the Antilles as a point of departure. The first issue that preoccupied him was national identity in view of the colonial past. That is also the theme of his first novel, The Ripening. He considered the blend of languages and cultures a decisive characteristic of Antillean identity: “In the Antilles where I come from, one can say that a people is positively taking shape (constructing itself). Born from a melting pot of cultures, in this laboratory where each bench is an island, here is a synthesis of races, customs, knowledge, that is striving towards its own unity.”

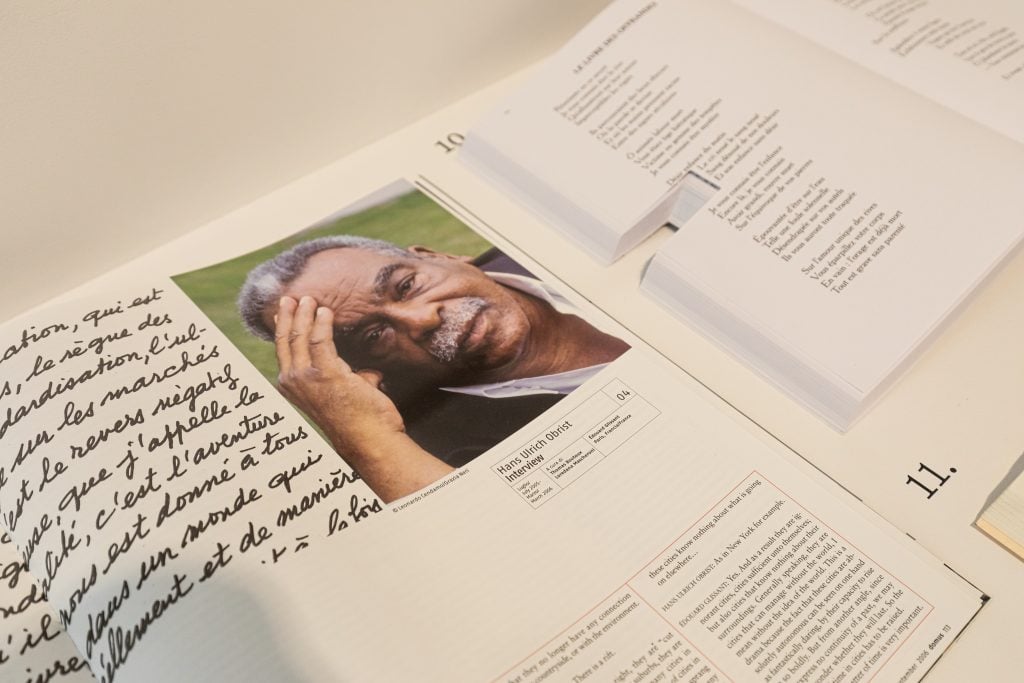

A photograph of Édouard Glissant at the Luma Arles exhibition, alongside documents from one of his many conversations with Hans Ulrich Obrist. Photo: Adrian Deweerdt.

On the basis of these insights, he later observed that there are similar cultural fusions all over the world. In the 1980s, a period in which a theory around globalisation was developing, he expanded on the concept of creolization in collections such as Caribbean Discourse: Selected Essays, applying it to the process of continual fusion, noting that it’s a process that never stops.

In one of our many conversations, Glissant told me that “the American archipelagos are extremely important, because it was in these islands that the idea of creolization, that is, the blend of cultures, was most brilliantly fulfilled. Continents reject mixings… [whereas] archipelagic thought makes it possible to say that neither each person’s identity nor the collective identity are fixed and established once and for all. I can change through exchange with the other, without losing or diluting my sense of self. And it is archipelagic thought that teaches us this.”

“Archipelagic thought,” which endeavors to do justice to the world’s diversity, forms an antithesis to continental thought, which makes a claim to absoluteness and tries to force its worldview on other countries. To counter the homogenising force of globalization, Glissant coined the term “globality” for a form of worldwide exchange that recognises and furthers diversity and creolisation.

Glissant’s conception of a museum also extends to the ways in which we understand the function of the exhibition. He told me that, so often, exhibitions are presented in a way that is invisible to large sections of society. This idea also connects to the multiplicity of language: the world can be expressed in not one, but many different ways. We can move between different languages as they provide gateways into different worlds, beyond the closed quarters of a particular landscape, nation or identity. As Glissant told me in our last conversation, we must remember that neither each person’s identity nor the collective identity is fixed and established once and for all.

For Glissant, utopia was a place, he wrote, where “all the world’s imaginations can meet and hear one another without dispersing or losing themselves. And that, I think, is utopia, above all.”

Perhaps you can see why I’ve been thinking a lot about Édouard Glissant. As an agent of change, he remains perennially relevant amid discussions around repatriation, justice, and where beauty fits between them. As he said, what matters is the production of reality. In regard to museums, he imagined them as networks of relationships, quivering places that could transcend established thought systems and serve as meeting points of the world’s culture. Although unrealized, his ideas for a museum remain a source of wondrous possibility.