Opinion

Protesters Are Taking Down Monuments Across Europe. So Why Is Germany Redoubling Its Commitment to Conservative Symbolism?

The installation of a cross atop Berlin's Humboldt Forum stands in stark contrast to other actions around the world.

The installation of a cross atop Berlin's Humboldt Forum stands in stark contrast to other actions around the world.

Kate Brown

It glimmers against the Berlin skyline: an enormous golden cross on a colossal domed building. And while crosses are not an unusual sight in any European capital, this one sits atop the Humboldt Forum, a major, €644 million ($711 million) new museum that will house Berlin’s non-European and Asian collections—including questionable objects culled during the colonial era—when it opens at the end of 2020, a new timeline that was just announced today, June 16.

With the toppling of monuments to colonialism and white supremacy proliferating around the world in recent days, the gilded Christian symbol, which went up at the end of May, feels more than a bit out of touch with the current moment. Even Berlin culture senator Klaus Lederer said the cross was “a clearly religious sign” that runs counter to the museum’s mandate, according to Deutsche Welle.

Nor is the cross the only Christian symbol on the dome. Around the cupola, phrases lifted from the Bible dictate the dominance of global Christianity: “There is no other salvation, there is no other name given to men, but the name of Jesus… all of them that are in heaven and on earth should bow down on their knees.”

Despite the strength of those words, the symbol, and the signals sent by putting a non-European collection inside a reconstructed Prussian palace, the museum maintains that the cross and the script are open to interpretation. “Ambiguity is part of our DNA,” said Hartmut Dorgerloh, the institution’s general director said in a recent interview.

Yet a highly charged movement, existing for decades and spurred into the streets following the death of George Floyd in May, has reached Europe. Among actions taken to remove statues of ex-slave traders or ill-gotten objects from the colonial era, institutions are facing a renewed challenge over the legacies they celebrate. The cross-topped gilded palace as a target of that discourse has rendered itself unmistakable.

People protest against racism and police brutality on June 6 in Alexanderplatz. Photo: Maja Hitij/Getty Images.

In a statement, the Humboldt Forum Foundation’s board of directors said that they “expressly distance themselves” from “any claims to power, sole validity, or even domination that can be derived” from the inscriptions and icons on the building, saying that the symbols are simply “quotations from architectural history.” Several articles, including dissenting ones, are published on the museum’s website.

To some experts from the museum community and art world, the answers and gestures at discourse from the Humboldt Forum do not justify the cross’s reason for being there. It “sends problematic signals to the world if Germany raises a symbol of White Christian superiority” atop a museum of non-European art, says Mirjam Brusius, a research fellow in colonial and global history at the German Historical Institute in London.

She says it’s especially ironic that one recent Black Lives Matter protest in Berlin drew 15,000 people to the streets just steps away from the museum. The museum has released no press statement on the matter.

“The contrast is stark,” she says. “Germany of all places can’t afford to fall behind when it comes to debates concerning racism. Denazification in the country has not worked in the ways many have assumed, and antisemitism and racism never went away.”

Of course, it does not stand alone; there are other contested colonial monuments around Germany. In Bad Lauterbach, there is a statue of colonial general Hermann von Wissmann, who torched villages and executed locals in what was then German East-Africa during his colonial exploits during that late 19th century.

There are the so-called Askari-Reliefs, which celebrate Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, a colonial war criminal who was nicknamed the “Lion of Africa.” Due to protests over the past years, the monuments have been closed off from the public.

And in Berlin, there are several sites that carry racist names, such as the Mohrenstrasse train station, which is near the Brandenburg Gate. In German, “mohr” is a derogatory term for a black person. Other street names, which celebrate imperial conquests, were motioned to be changed in 2018.

The inscription below the top of the dome on the Humboldt Forum, which is a combination of two Bible quotations. Photo: Bernd von Jutrczenka/dpa via Getty Images.

Yet on many other fronts, as the UK, Belgium, and the US are being forced to comprehensively revise their monuments to dark histories, the German state is, in some key instances, going in the other direction.

On Thursday, June 11, the German culture ministry posted on Twitter that it would be promoting the restoration of 40 monuments throughout the country. According to a spokesperson from the ministry, the state intends to devote €30 million ($34 million) to the project.

The culture ministry declined to comment on the monuments in Britain and Belgium that celebrate those countries’ dark and painful pasts, but promoted its new plan on Twitter by stating: “Cultural monuments are an essential part of our cultural heritage.”

But to some in the arts community, that sounds like willful ignorance of a global movement to reassess statues and monuments in public spaces. And while Germany has made important reparations to survivors of the Holocaust, including the restitution of artworks and objects, and the construction of memorials, it has done far less to repair the damage of its late 19th-century and early 20th-century colonial projects, including the genocide of the Herero and Namaqua peoples in what is modern-day Namibia.

“The extreme violence in the colonial enterprise cannot be forgotten,” said Cameroon-born and Berlin-based curator Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung in a recent radio program. Ndikung added that the cross being erected over a museum of colonial-era collections is a display of “dominance” and “supremacy.”

If the Humboldt Forum wants to lead the conversation, “it now has to start with this cross and its role within as well as outside Europe,” says Jürgen Zimmerer, a professor of global history at the University of Hamburg. “Whereas all over Europe colonial monuments are dismantled, Germany erects a new one in Berlin.”

Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. Photo courtesy Rony Hartmann/AFP/Getty Images.

Certainly, the erection of the cross a few weeks ago, which is designed by Franco Stella and is a replica of the one that once sat atop the original Prussian Palace on which the Humboldt Forum is modeled, is no surprise. Its planned installation was first announced in 2017, and the institution published several essays from officials and experts to explain its relevance.

But even an article published by the museum admits that the announcement of its “dominating” presence flew under the radar for years.

“Franco Stella’s winning design included the cupola and cross, but at this point in time, most of the general public had not really noticed this,” Laura Laura Goldenbaum, an art historian and academic advisor at the Humboldt Forum Foundation, wrote last month in the museum’s online magazine that floats debates on the subject of the cross, called “What It All About?” (According to Goldenmann, the cross was not included in a wooden model presented in 2008.)

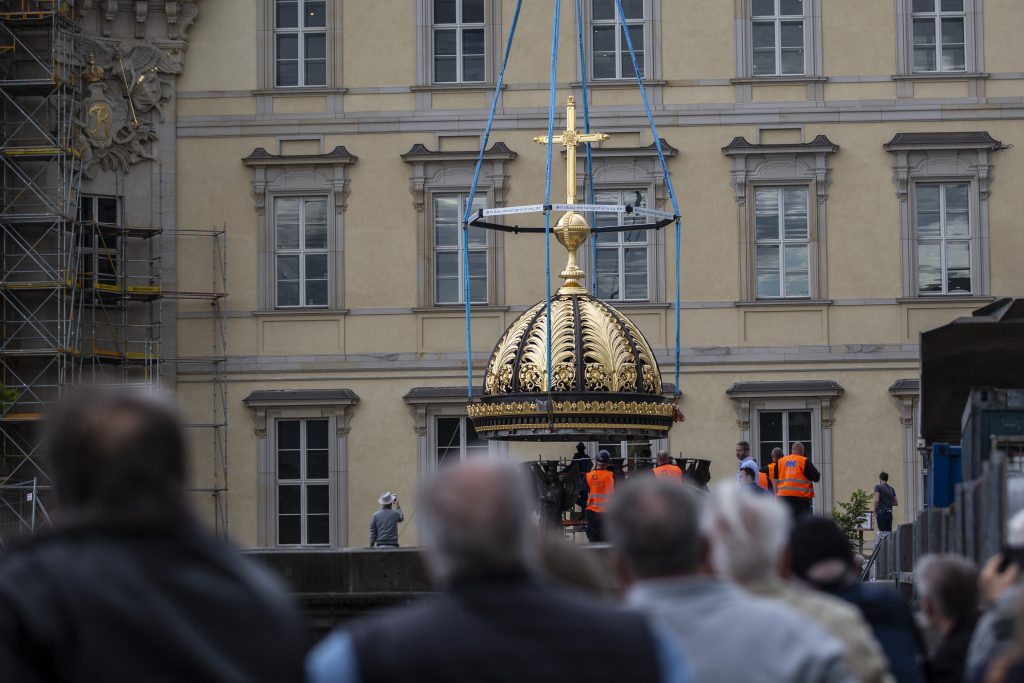

But no one can miss it now. On May 29, four days after the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Berliners gathered to watch the gilded sign of Christ be lifted onto the 17-ton cupola of the reconstructed Prussian Palace.

People watch as the cupola and cross onto the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. Photo by Maja Hitij/Getty Images.

I watched with a similar feeling of confusion in 2018 when a 52-foot-long boat from Oceania was craned into the museum before the front wall of the palace was built because it would not otherwise fit through the door. At the time I called it “a gesture terminal enough to feel macabre.” Despite debates, essays, and press releases occurring since then on the subject of how to manage German and European colonial legacies, with a particularly strong eye cast on the Humboldt Forum, a cross hangs above the museum. What is argued as being ambiguous is nevertheless also very terminal. It’s not going anywhere.

But some things do change. The museum may create a forum for ideas about its collections, architecture, and its very existence, but, outside, the air is fundamentally different. People are in the streets now, and they’re knocking on doors.