Opinion

What Can Joseph Beuys’s Mythic Boxing Match Teach Today’s Activist Artists?

Does politically engaged art have to come up with ideas to solve the world's problems?

Does politically engaged art have to come up with ideas to solve the world's problems?

Alice Bucknell

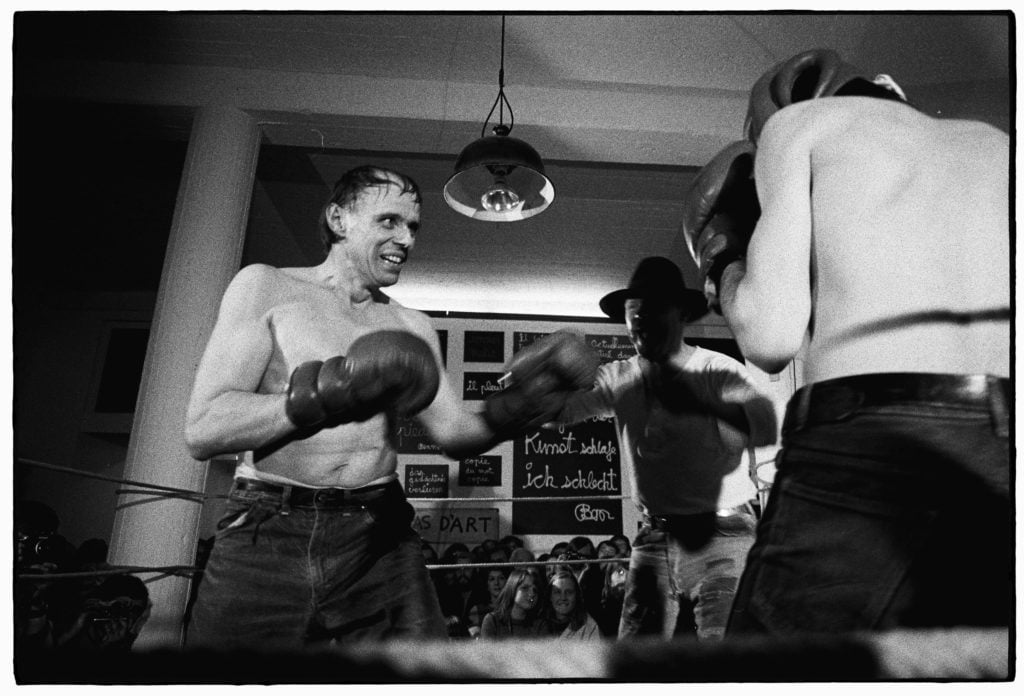

On October 8, 1972, as part of a “farewell action” to documenta 5 in Kassel, Joseph Beuys entered a boxing ring with local art student Abraham David Christian. Ceremoniously capping off 100 days of intense debate on social-reform issues with visitors to Beuys’s pop-up political office Büro der Organisation für Direkte Demokratie durch Volksabstimmung (Office of the Organization for Direct Democracy by Referendum), the two pugilists fought in a riotous three-round match of punches and counter-punches. Beuys came out on top and was announced the winner by referee Anatol Herzfeld, an ex-student of his. The victory was symbolic of the artist’s crusade for a “direct democracy,” over the ruling order of “representative government.”

Beuys’s Boxkampf für die direkte Demokratie (Boxing Match for Direct Democracy) operated inside the formal framework of the high-art world (i.e. documenta) to fuel the fire of real-world political disruption spun out of the post-war “cultural turn” of the ’60s. Infusing the topics of debate hosted by his Office—from educational reform, to atomic energy, to race relations—the performance, to borrow a boxing metaphor, inflicted critical damage while staying light on its feet: the seminal boxing match, alongside Beuys’s installation, usurped the throne of the mega-quinquennial fanfare of documenta 5.

As a spectacle within a spectacle, the project bled across mediums, art-world economies, and broader socio-political systems with the simultaneously lighthearted and accessible but still profound mysticism characteristic of Beuys’s practice at large. This porosity let Beuys bypass the anti-revolutionary blockades imposed by high-art circles as a partially camouflaged activism that today’s politically engaged artists could do well to emulate.

Joseph Beuys, Boxkampf für die direkte Demokratie at documenta V, (1972). ©Hans Albrecht Lusznat, 2017.

As many critics have noted, much of this year’s overtly political art ended up awkwardly in bed with the same power structures it tried to expose: from the refugee-sponsored supercapitalism of Olafur Eliasson’s Green Light workshop and neocolonialism of Ernesto Neto’s performance Encounter with the Huni Kuin in Venice, to the so-called “disaster tourism” of documenta 14. Ironically, the more reactionary the work wanted to be, the more problematic it became, like fighting against quicksand. Perhaps Beuys knew best by leaving a space for ambiguity.

In his contributing essay for I Can’t Work Like This: a Reader on Recent Boycotts and Contemporary Art, published by Sternberg press in early 2017, artist and writer Gregory Sholette calls out an apparent double standard levied against artists whose practices veer into the political. “If social activism by doctors and lawyers does not diminish medical or legal expertise,” Sholette asks, “what is it about the labor of the artist that leads to charges of deceit so onerous that it tars the identity of what it means to be an artist?”

Here’s one answer: The double-standard of the artist as both poetic mediator and whistleblower, it would seem.

Artists involved in direct political action are lambasted for degrading serious culture and mutating their practice into bunk propaganda. Meanwhile, the artist in society has usually been put on a high altar for exposing political scandal, state-perpetrated violence, abuse of power and crisis. Digesting these cultural uglies and re-presenting them through a democratic visual language seems to be the only legitimate avenue for social art practice.

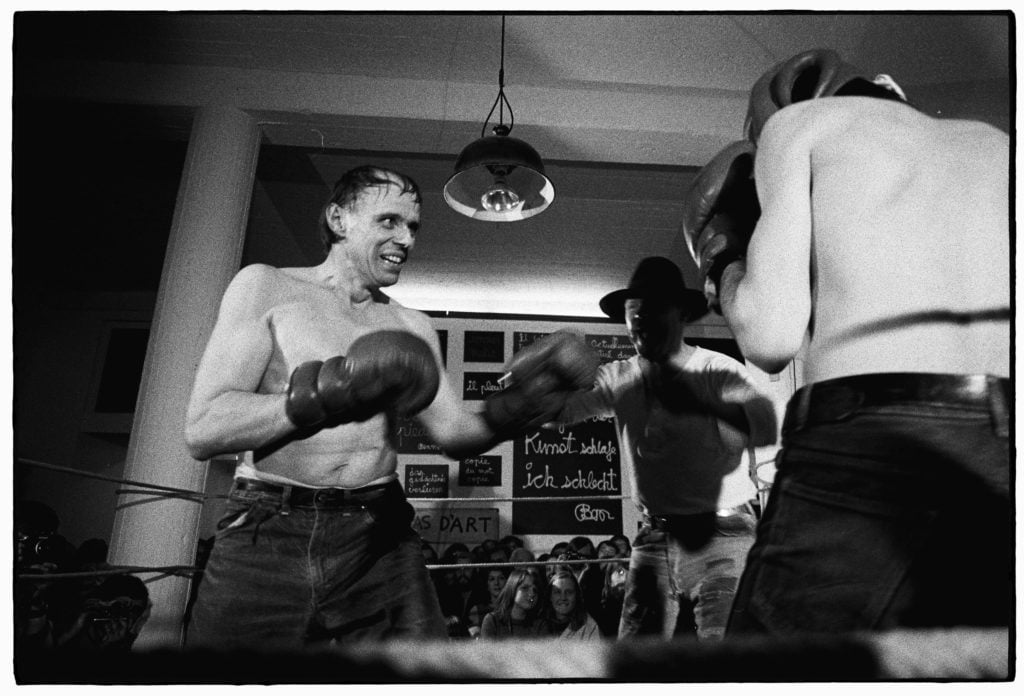

Joseph Beuys, Boxkampf für die direkte Demokratie, (1972).

One need look no further than the extreme economic and political duress of the 1930s and 1960s, which led to some of modern art’s most significant movements—Abstract Expressionism, the performative turn, and the rise of conceptual art—whose manic genius not just revealed but aestheticized these chaotic postwar political climates.

Could the spike in politically engaged practice today indicate another cultural turn? And in this age of “fake news,” what strategies could artists borrow from Beuys? Many writers (including Sholette) criticize today’s political art for throwing sand in the eyes of the prevailing political order without offering coherent counter-ideologies. But this was the brilliance of Beuys’s art: it could give space for new ideas to breathe into being and draw an ecstatic inspiration from the insanity of a crumbling world order.

Beuys’s politics was, of course, left-leaning—just like everyone else embedded in the postwar artist collectives of the ’60s and ’70s. As the co-founder of the Fluxus movement in 1962, the German Student Party with Johannes Stuettgen in 1967, and the Organization for Non-Voters and Free Referendum (1970), Beuys’s work was fundamentally infused with the political climate that contextualized it. But he never let politics pigeonhole his art practice. Rather, Beuys worked within art-world superstructures to create new political imaginaries: to bring art into politics, and not the other way around.

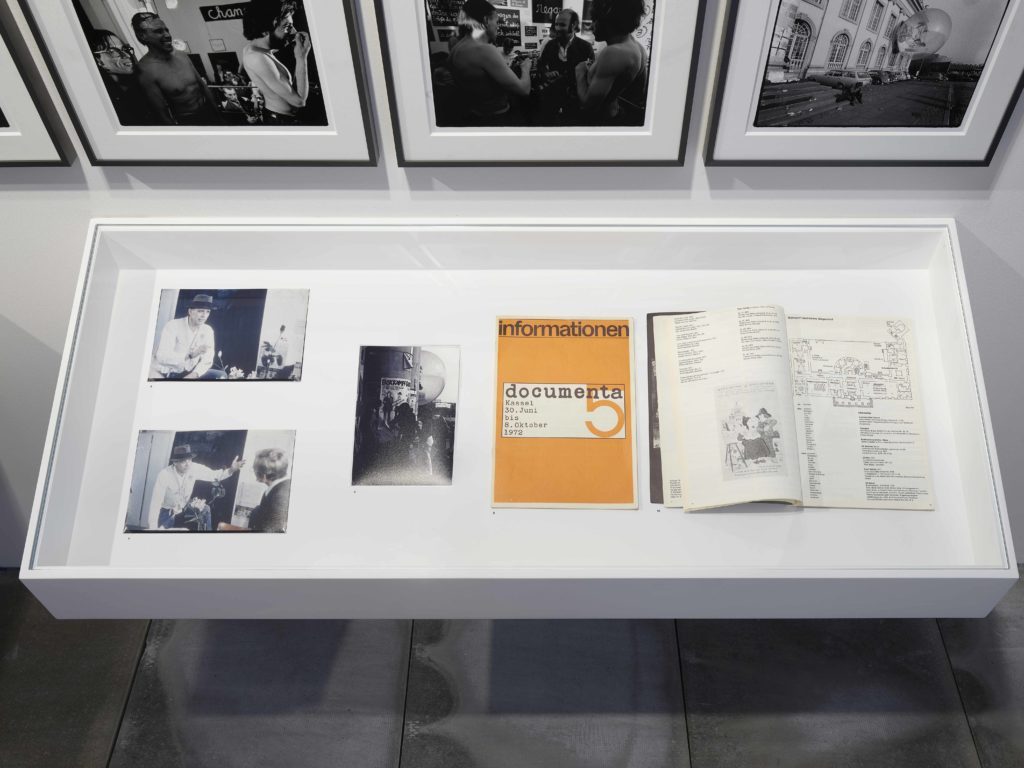

Installation view of “Joseph Beuys: Boxkampf für die direkte Demokratie,” Courtesy Waddington Custot

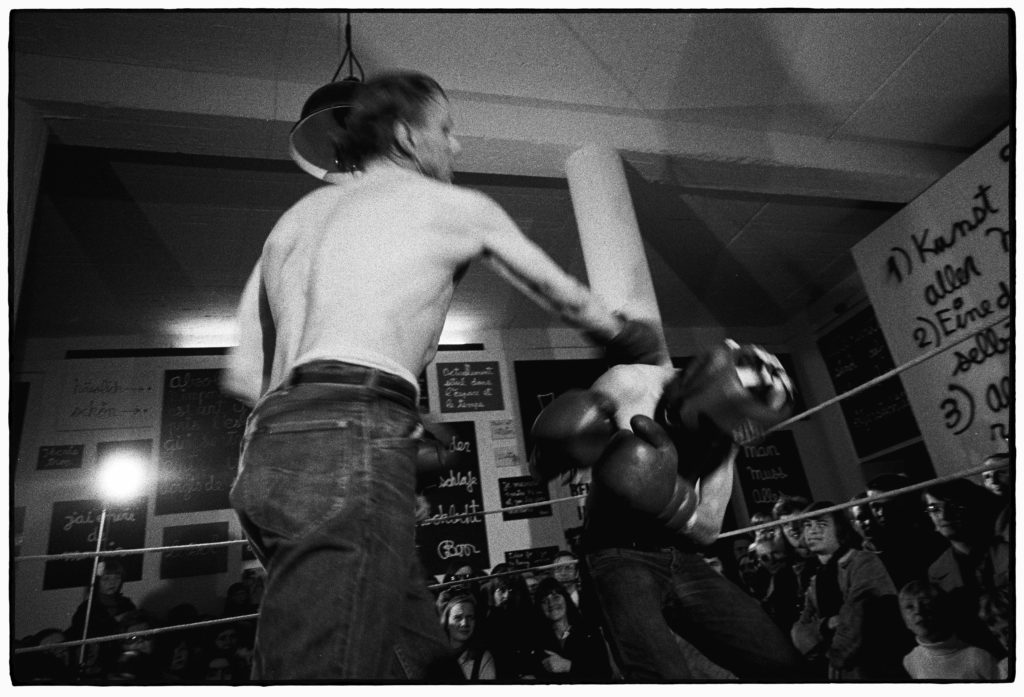

Ironically, the most riotous political art often enters the art market in the most sophisticated formats, with the highest price tags at the swankiest galleries. Beuys’s Boxkampf für die direkte Demokratie exists as a public memory, an event, a social sculpture, a nine-minute-and-30-seconds-long video of archival footage documenting the fight, 40-some-odd photographs, two letters from Galerie Holtmann indicating its successful sale, an event poster depicting the two competitors standing side-by-side sporting large cartoonish gloves, and various paraphernalia relating to Beuys’s contributions to documenta 5.

Most of these archival materials—including both competitors’ original boxing gloves autographed by Beuys, boxing headgear, and the jumbled remnants of ringside rope—are currently on view at Waddington Custot in London. With a near-mythical aura, they sit inside a gritty meta-gallery of raw concrete tiling and drywall, encased within a plywood-and-steel exoskeleton designed by David Kohn architects exclusively for the exhibition, which bisects the original venue.

Installation view of “Joseph Beuys: Boxkampf für die direkte Demokratie.” Courtesy Waddington Custot.

The contrast between the gallery’s famed Cork Street digs (flanked by the likes of Pace Gallery and the Royal Academy of Art) and the fabricated exhibition space is effective and weirdly satisfying: One can almost see the wild-eyed Beuys in the photographs—sweaty, shirtless, and grinning with glee—taking a clairvoyant delight in this unexpected presentation.

In politicizing his practice and aestheticizing the political, Beuys’s “social sculpture” sits at the ebb-and-flow of social disruption, simultaneously cozying up with art-world paradigms and undoing them underneath the dinner table.

In our “post-truth” era, where mysticism is employed as tactically in politics as in art (if not more so), there may be much to learn from rolling with some of the punches in order to open up the right space for that unexpected blow.

“Joseph Beuys: Boxkampf für die direkte Demokratie,” is on view at Waddington Custot, London, July 7–August 11, 2017.