Opinion

Nothing Fishy Here! Kenny Schachter Squeezes His Way Into the Thick of Things at Yet Another Art Basel

Our columnist cruised into the Swiss art town with a fleet of classic cars—and found plenty of art to rev his engines.

Our columnist cruised into the Swiss art town with a fleet of classic cars—and found plenty of art to rev his engines.

Kenny Schachter

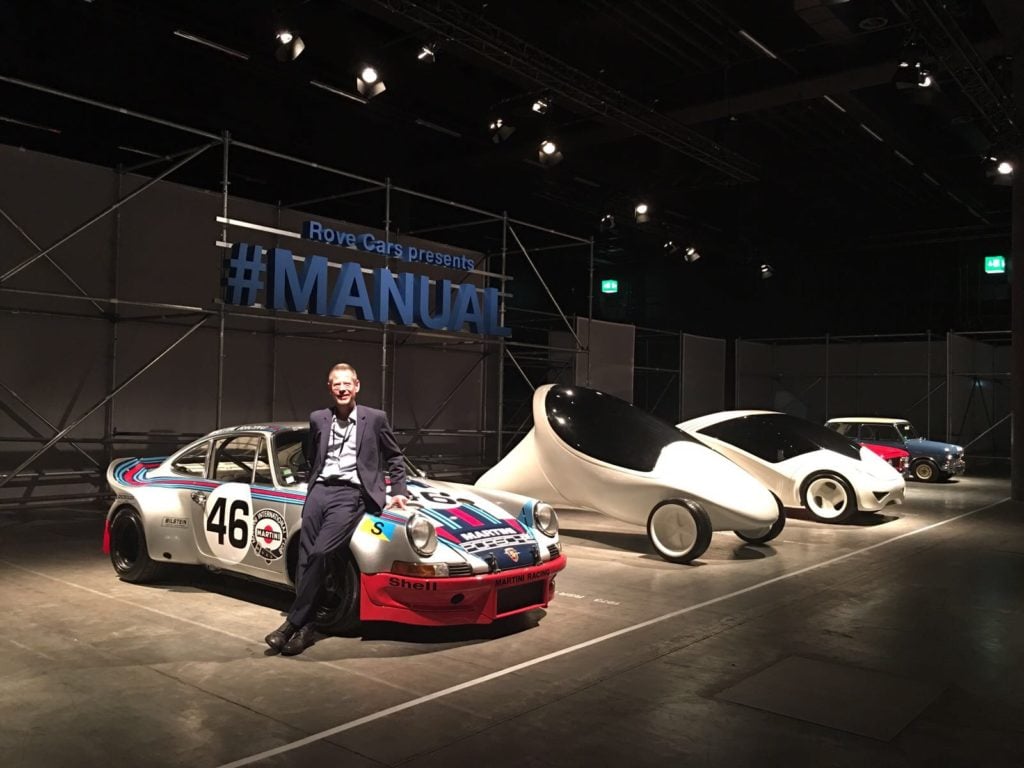

Two years ago, when I was driving home from Art Basel, I suffered facial injuries in a car accident. This year, I rolled back into the art-industry town with an automotive vengeance: an exhibition of 13 cars (for luck) entitled “#MANUAL,” featuring a pair of Zaha Hadid prototypes I commissioned between 2005 and 2008. A lot was riding on the week in other ways as well, with two daunting art talks scheduled—one pairing me with Hans Ulrich Obrist (part of the Executive Masters in Art Market Studies class I lecture for at the University of Zürich), and the other with frenemy Adam Lindemann at the venue of the car show, Design Miami/Basel. (Time to drop the Miami, maybe?) An article I had to write for CNN’s website on the convergence of art, design, and classic cars was sandwiched in between.

Now, some trivia: BaselWorld, the watch and jewelry fair that takes place every March at the Messeplatz, is almost 50 years older than Art Basel and far exceeds its scale, with over 2,000 exhibitors compared to under 300 for the art version. Though the timepieces take up much more space, visitor numbers are about the same at each event—roughly 100,000. But I imagine the gross value of art exchanged over the course of the initial hours of the first day of Art Basel handily beats BaselWorld. And there isn’t a better place to see such a gorgeous and diverse concentration of art of all stripes; which, according to your predilection, might be good, bad, and/or ugly. Like Klara Lidén’s stolen trashcans at Galerie Neu, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

University of Zürich lecture at Parkett Publishers with Hans Ulrich Obrist and Nicolas Gallery. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

There were no celebrity sightings to report in Basel. I’d guess that’s in part due to the paucity of parties and the crackdown on Jho Low, the 36-year-old accused of pilfering billions from Malaysia and pornographically spending it on boats, real estate, jewelry (I wonder if he visited BaselWorld), and art presents for his pal Leo DiCaprio. The absent DiCaprio, who just “voluntarily” disgorged the Picasso and Basquiat works (and Marlon Brando’s Oscar) gifted by the other JLo, was probably gun shy of the publicity he’d inevitably attract. He always is, unless surrounded by a passel of pretties (for PR no doubt). I’m amazed Leo held on to the artworks for so long (a year or so), since he’d give Stefan Simchowitz a run for his money on the flipping front. How come I never get gifts like that?

The hottest restaurant in town was Chez Donati, not least because of the scorching heat outside (such European airs!); with neither air conditioning nor fans, things at ratcheted up past stifling during the dinner service before the convention center opened. Seated around the tables were Roland Augustine of Luhring Augustine ribbing Stellan Holm that jeweler/collector Laurence Graf had replaced him with another dealer during the meal, the brilliant legend Paula Cooper holding court, and the rest of the A-List art aristocracy, for better or worse. I was stuck in the middle of a pressurized vice grip of hostility, between Anton Kern (we mostly overcame a history of differences) and Fergus McCaffrey.

McCaffrey, who is still pissed that I keep mentioning how his repeat-offender Sigmar Polke keeps reappearing at multiple fairs (only to be outdone this year by another Polke from another dealer; read on), jostled me exiting poor Paula’s table—I thought I saw a steam coming out of his ears. And Larry G. and Chrissie Erpf, also present, are engaged, congrats! The Brancusi show Gagosian did decades ago in New York remains the best gallery exhibition I’ve seen, besides anything involving John Richardson.

Kenny’s car show at Art Miami/Basel. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Design Miami started in Miami (funny enough) in 2005 and expanded to Basel in 2006—making this year the 12th edition in Basel and 13th in Miami. I did the first Basel iteration and nearly fainted in my booth, which I had to abandon unattended in the middle of the opening to get an EKG at Basel University Hospital, but that’s another story. Unrelated, I quit doing art and design fairs about 10 years ago, preferring to wade the aisles instead of waiting for clients, a captive in a booth. In spite of this, I snuck into Design Miami/Basel this year in the back of a 1952 Lancia Aurelia B20 GT, part of a collection of quirky, off-kilter cars from the 1950s to the 1990s that I assembled over 13 years living in the UK. I was also there to present 1:1 scaled conceptual models by Hadid, whom I had exhibited often before, and terribly miss.

My wheels were ostensibly “not for sale,” which translated into “kind of for sale” in the early stages of the fair to “would someone please make a goddamn offer” midway through. The majority of the cars were day-sale material, but it was an effort driven (pun) more by love and appreciation than anything else. Especially for Zaha. I forgot how mentally and physically draining these enterprises are—from an aching back to sore feet and the feeling of always having to pee (and not being remotely near a urinal). Then there’s the joy of comments such as, “Why is your 1961 Alfa Romeo Giuletta Spider in such a horrid state of disrepair?” It’s called hard-fought patina… Jesus. It was at that point I added my hips to the list of infirmities.

Kenny’s contraband Adidas for Art Miami/Basel. Collage by Kenny Schachter.

Among the most astute and successful private dealers, Philippe Ségalot, all but invented (along with Tobias Meyer) the supercharged contemporary art evening sales as we know them today: in equal measures sexy and profitable (well, less money than glamour these days). Ségalot was interested in a Lancia and photographed it with an aficionado’s perspective for detail. Then the door lock wouldn’t cooperate and he couldn’t get in. (Like art dealers, cars are temperamental.) Stuart Gurr, my trusty mechanic/gallery director, had to subsequently break in like a street hooligan. It reminded me of a racehorse a friend used to own named Keep Hope Alive—it never won, but it never hurt to think it might.

Meanwhile, a design dealer hemmed and hawed over another Lancia (but hightailed out of town before committing). Shamefully, the carmaker produces only a single vehicle in Italy, something called an Ypsilon. Could I sell crack to a crackhead? Don’t answer. And why is there only interest in the things you can’t part with?

Stuart Gurr, my trusty mechanic/gallery director, caught out breaking into my own car, a 1952 Lancia B20 GT. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Across the aisle from me was a Japanese ceramics dealer, and not only did she change the objects in her booth continuously, even when foot traffic minimal, she swapped out the shelving and display apparatuses too—and, more astonishing, she changed her outfits no less than three times a day. She’d give Cher a run. Stuart was flabbergasted.

Jean Prouvé (1901-1984) was a French metal worker and self-taught architect and designer (thanks, Wiki!) of reductive glorified conceptual sheds, prescient in their utilitarian portability, inexpensive to manufacture, and prideful in stance. The extraordinary Parisian 20th-century design dealer Patrick Seguin is equally as brilliant in having fostered this market from zero to €8,000,000 over the course of 25 years running his eponymous gallery.

As the owner of 23 Prouvé houses, the gallery is the largest collector of those design artifacts (doll houses for rich people, I’d jokingly call them, but I’m in awe of Patrick’s connoisseurship and success). Fifteen have been sold over the years to the likes of Miuccia Prada and Yusaku Maezawa—Warhol’s aphorism should be updated to “Everyone is famous for $150,000,000”—and Richard Prince, who could garage one of his 1960s American muscle cars inside. The Jean Prouvé Tropicale House was auctioned by Christie’s for $4,968,000 in 2007.

During the fair, each night ends at the Three Kings Hotel (or Kunsthalle bar), and, with the precision of Swiss clockwork, everyone is toast by 2 a.m., from Larry G. and the Mugrabis to galleristas, male and female, the world over. It’s fun, I must say. Your fiercest enemies—like, for instance, the mercenary Loic Gouzer of Christie’s—take on a whole new sheen when you realize how hard they work, how knowledgeable and passionate they are, and what a chore it must be to get people to relentlessly sell art they don’t want to sell to buy art they don’t want to buy. The 15 drinks didn’t hurt either.

The terrace bar of the Three Kings should be called the Three Stingels, that’s how many works I was offered before I could order a cocktail. By 3 a.m. it’s like the crowd was sprayed with truth serum—a moment to engage in some strategic reportage (by typing up everything I can, otherwise it may as well have not happened). You discover the darnedest things about people you know and work with, like which friend/client is actually not paying their invoices in a timely fashion. I still wouldn’t trade my trade for anything. One art adviser (aka JPEG jockey) generously offered me a drink, which I (of course) accepted. By the time he left, I got stuck for his 200 CHF bill. In the art world, nothing free is free.

Fairs rule the roost, exerting a disproportionate stranglehold on the flow of commerce like an art dam, so participants must endure the capricious politics. Basel is Don Coreleone (The Godfather Part I), and a contract seems to be out on the head of Art Cologne’s Daniel Hug. But diverting attention from the threat of Art Basel opening yet another freaking fair in Düsseldorf—a point-blank attack on Cologne—the Swiss fair instead came out swinging against… auction houses for some odd reason. What have they got to do with it (insert laughing emoji)?

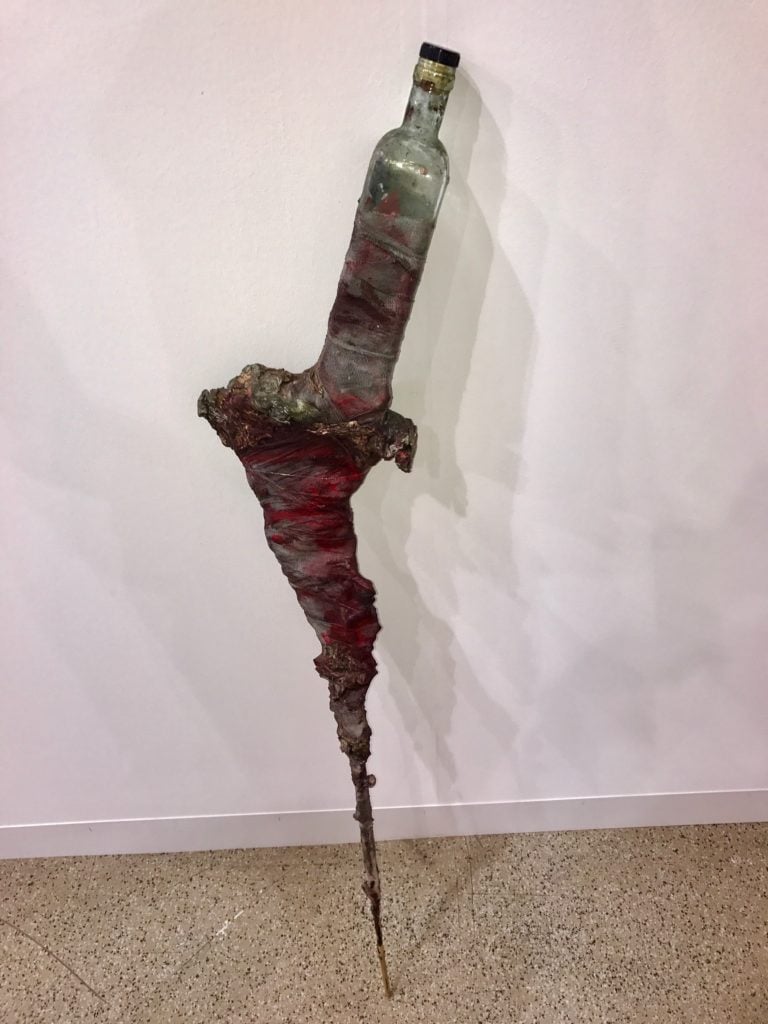

Franz West at Eva Presenhuber at Art Basel: A wounded soul(dier). Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Downstairs in the big tent are the stalwarts like Acquavella, Nahmad, Gagosian, Lévy Gorvy, Hauser & Wirth, and Zwirner, and upstairs is a mishmash of less-market-driven material, some of which is sure to be the next fidget spinner (ask your kids). As a dealer-to-dealer dealer (like many others similarly situated), galleries are my distribution network dotted throughout the fair. It’s a sport trying to identify the beneficial owners of particular works in the big secondary booths. It’s a pretty fail-safe measure to sell at the fairs for the approximately 10 percent tithe it generally costs in fees, though I did hear a disheartening tale from a lawyer regarding one of my consignées before the proceedings, but I’ll give him the benefit of doubt.

Greek megacollector Dimitri Mavrommatis, staying at the cut-rate Radisson Blu Hotel (which still costs two arms and a leg during the fair), was overheard hassling housekeepers at the shitty hotel—but, you can’t blame unsympathetic guests paying extortionist rates to live in an art-world sardine can for acting out. At the fair, I overheard a collector snapping at a dealer to back off and give her room to breathe. It’s one thing to have a good eye and an altogether different thing to have an extra set lording over you while making a decision whether or not to purchase a work.

Gagosian sold a super Stingel self-portrait obscured by a purple abstraction for $3.5 million and, outside of the booth, had a Grotjahn for $7.5 million that I had only just sold to Christie’s for $5.2 million. There was a Sigmar Polke at Barbara Gladstone for $1.3 million, though I was implored not to say so (shush), and a related work from a different series for twice the amount at Anthony Meier—such are art-world economics. Meier’s stunning Judd stack at $18.5 million will probably prove cheap in time to come. There was also a Polke at Meier with a hatchet and laundry basket that I’ve seen no less than four times at fairs past—at different galleries each outing—and hereby designate the MVP of Basel 2017. (Not most valuable player, but most fair visits for a painting.)

Sigmar Polke on the road again at Anthony Meir—a fair MVP for most consistent attendance. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I sold two Wayne Thiebaud works from Acquavella to clients, and still managed to earn no commission (don’t ask); leave it to me, achieving failure in success. The gallery also sold a Mugrabi-owned Basquiat for $15 million that the family only bought two years ago for $6.6 million, making for a hearty compounded return (CAGR) of 42.25 percent annualized. Simon Lee had a Christopher Wool for just under $8 million from the “collection” of spec-u-lector John Sayegh-Belchatowski (though the artwork started at a higher number), and a secondary-market George Condo with an asking price of $1.75 million, which is not as far-fetched as it initially sounds due to the nearly $2 million auction record for Condo’s ascendant paintings.

There also was another recently discovered Polke at Lévy Gorvy gallery that sold for around $12 million, which Michael Werner’s Gordon VeneKlasen told me was a steal. (What he didn’t disclose was his financial interest.) Cool as ever, Lisa Spellman of 303 Gallery called business ballistic on the first day, while other dealers resembled wounded animals—there’s clearly a Darwinian bell curve of winners and losers at play.

Michael Black, an old “friend” who once threatened to break both my knees over one deal or another, serendipitously bumped into my kids in Venice during the fair and generously volunteered that he only just sold his Guston to Hauser $12.5 million to buy a house; the gallery in turn sold the painting at the fair for $15 million a short few weeks later. That’s a fat—but fair for the great work—margin of 20 percent, so well done all around. Like peeling onion layers, I found another acquaintance that had traded Black the Guston for three Christopher Wool paintings. Art might benefit from being retrofitted with tracking chips (as the artist Jonas Lund actually did a few years ago). During New York’s May auctions, our friend Patrick Seguin sold his Grotjahn on a staggering $16 million guarantee, also to purportedly purchase a house. Forget comparing the art market to real estate, the new benchmark is whether your painting measures up to the price of a trophy property.

The promiscuous Guston. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Blum and Poe had new Julian Schnabel works on stand for $325,000 vs. Mark Grotjahn primary-market paintings for between $11 million and $14 million; I’m no Schnabel fan, but go figure. Eric Fischls are only $550k—pick them up at that level while you can. The 16-year-old son of Tim Blum, Lux (only in LA), has been manning the booth in Basel for years now. (A kid after my own heart, as I draft mine into action whenever possible.) I questioned Lux regarding his fair experiences, to which he replied: “One of the most interesting things I’ve noticed after working the fair for three years is how it has become more packed with art advisors rather than the collectors that crowded the halls only a few years ago.” When told by his folks of permissible discounts he responded, “Why give discounts at all?” Next, he’ll be after my writing slot at artnet.

I forgot the blinders you’re forced to wear when participating in a fair; I not only couldn’t see past my nose, I didn’t have the inclination. Tunnel vision is putting it mildly—thus, sadly, for the first time, I missed the Liste fair of emerging art and the Untitled curated portion of the fair characterized by the XXXL size of the installations. C’est la vie. What I did see was a blistering demand for art showing no sign of abatement. I’d go as far as saying it’s continuing to steamroll ahead at increasing velocity (to go back to car-speak)—and in Switzerland, even Uber functions better. I actually heard people relating their birthdays falling during specific fairs—we mark our lives through art, for better or worse till death do us part. And in the case of lasting art, afterwards too! Next up: “Nuclear Family” a group show at Ibid Gallery in LA opening July 15 through August, featuring my wife and kids. Idleness is the devil’s best friend, and I’ve got enough mischievousness in my family as it is.