I cannot tell a lie (as many know firsthand—sorry): Although I was in LA at the time, I didn’t go to Art Los Angeles Contemporary (ALAC), Spring Break, or even Felix, really, although I participated in the fair. I didn’t go to the inaugural Los Angeles version of Frieze either, an omission unrelated to the fact that they withdrew my early-entry VIP card and didn’t bother to offer a consolation later-entry pass. The truth is, I was too preoccupied with my solo show at Niels Kantor Gallery and my room in the Hollywood Roosevelt where I was participating in the Felix hotel fair.

Just because I barely budged, however, doesn’t mean I have nothing to report. On the contrary: here is a bird’s-eye view from the trading pit that is today’s art-fair booth (or hotel room, in this instance).

There hasn’t been a major earthquake in LA for 25 years, and while Frieze et al. shook things up art-wise, no one was hurt in the proceedings. (That’s not to say there wasn’t the occasional art casualty; read on.) A collector whose house I visited had no art above any of the beds and everything was framed without glass in anticipation of the inevitable Big One. Just as dangerous (for me, anyway) was trying to cross mega-intersections in LA, a city where walking is generally frowned upon if not on a trendy trail somewhere. There was one juncture where I counted nine streets feeding into one; my strategy was to close my eyes, pray and run.

I hate to generalize but I find Angelinos nicer than the Brits or New Yorkers, yet not without concomitant drama. Just as the art festivities kicked off, a full-blown gun battle unfolded directly across from Nino Meir’s gallery compound during an attempted robbery of Usher (everything is celeb-driven in Hollywood, even crime). By the way, Meir, an Austrian former painter and restaurateur, hosted tasty shows across his three galleries by André Butzer, Arnulf Rainer, and Werner Büttner, who I just wrote an essay on for his upcoming Marlborough exhibit.

Werner Butter at Nino Mier, painting so bad it grips me, and has since the beginning of my career. I’m a fan. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

The Big Fair I Didn’t See

What is it about Frieze coming into town that seems to unleash the onset of biblical scaled fury, like a Bill Viola super-slow-mo video, whether it be via scorching heat (c.f. last May in New York) or torrential rains, which seemed to paralyze LA the way a light snow dusting does in London? Starved for human interaction as I am, I got an earful of feedback on the fair while I sat at my Felix perch—and it was, across the board, overwhelming positive. Why was everyone so happy about Frieze? Was it due to the legalization of weed? The layout was by all accounts airy and easy to navigate due to its Lilliputian size (about 70 participants); the criticisms, if any, amounted to “different city, same tent”—in other words, that the art was largely indistinguishable from any other major fair. But, without doubt, Frieze’s debut was an unequivocal social and economic home run.

Felix

Staged at the same Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel where Marilyn Monroe’s ghost has been repeatedly sighted in a certain full-length mirror (originally located in her regular poolside suite, it has now been relocated to the lobby), Felix was launched by collector Dean Valentine and the Morán brothers (Al and Mills, who run gallery Morán Morán gallery) as another by-invitation fair. For some odd reason, they invited me. Like an apparition from hotel fairs past—I might be the only Felix participant who actually did the Gramercy International in the mid-1990s, from whence this fair’s concept sprang—I returned from roaming the aisles as an intrepid reporter to sitting the booth like a hood ornament on a beat-up old Cadillac.

The concept for my room, co-curated with fellow artist/dealer/writer Joel Mesler, was to pair art by my talented family with works from my collection by artists like Cady Noland, Chris Burden, Vito Acconci, Robert Colescott, and Wade Guyton. (It was the fifth iteration of my traveling show.) I prepared a pre-fair PDF of the loot—but, as a dealer-to-dealer dealer, I didn’t know who to send it to. Maybe I’ll reconsider next time so I can sell more than three pieces.

George Condo (2004), Wade Guyton (2006), and Cady Noland (1991). Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

My lack of professionalism didn’t stop there. It was only the day before the opening that I was able to locate someone in the city who wasn’t bound to another gallery and could help lend a hand (I normally work alone). The lucky winner was a makeup artist; the interview consisted of the following line: “If you ever may have thought about selling art now is the time”; and while the whole point was to have someone cover the booth to free me up to see art, I ended up never leaving. So thick a “dealer” I am that after instantly selling an old George Condo drawing, it never occurred to me to note the details of the seemingly hordes of other buyers who afterwards inquired about purchasing the piece. So goes the art world: when a lot sells for a lot at auction, a lot of people all of a sudden want it.

Laid-back Felix was the perfect anecdote to stuck-up Frieze, though the execution was not without hiccups—a factor of its unanticipated success. Since it was split between cabanas by the pool and the 11th floor, access to the elevator (yes, only one) was like trying to penetrate a coagulated artery—all but impossible other than for the most valiant. It didn’t help that the fair was free, meaning everyone was a VIP. People were seen to visibly age in real time in the lava-like elevator line that never seemed to abate. Marilyn’s ghost couldn’t even gain entree. Hoards turned on their (Prada) heels and left, never venturing past the pool. Fire marshals are LA’s art-world gatekeepers. When I grumbled to my pals who run Felix, they replied ‘twas only I who had lodged a complaint; apparently you learn quickly how to spin a fair.

The other downsides of a hotel venue? Each “booth” was accessible only by a small door, which people had no compunction about blocking to catch up on chit-chat with old friends—and, worse, here was a bathroom in every room, where many exhibitors chose to hang art, and where many visitors chose to drop trou. Next time I’ll bring a six-pack of disinfectant. But don’t get me wrong—it was an extraordinary experience and I hope they’ll have me back

For my part, I didn’t even dare use the toilet for fear of missing out—despite the known risks of such behavior over time, including a weakened bladder, incontinence, and urinary tract infections. Then, for another malady, there are always artists trying to show you their work when things are at full blast, and things are repeatedly getting bumped into as a result of the close quarters. By the end of the weekend my nerves were so frayed that I was ready to lash out at children or animals. Which I did with Sage, my errant 16-year-old, who, by the way, contributed wickedly good paintings and sculptures. Art really is the grouting that binds us as a family.

Sage Schachter’s new works. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

For her own contribution, Ilona Rich presented a rainbow-colored, centipede-like dog thing that climbed the wall and emitted a cat’s meow, aided in its uncanny performance by a motion detector. Ilona, who happens to be my wife and who happened to skip Felix herself, managed to torment me from afar. I’d never dream of undermining the artist’s intent by doing something so crass as shutting if off—no matter how annoying and distracting it became, and even in the face of relentless questions, such as: “Was that a cat? Where is it? Under the bed? Was it your phone?”

Ilona Rich (ruf ruf), Joel Mesler, and Kathrine Bernhardt at Felix. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Being so publicly exposed was no easy feat—for me, at any rate—and I had to bob and weave like Muhammad Ali (or Matthew Marks at any given fair) to avoid bumping into my sworn enemies, aka the people I’ve written about. And, since you asked, no, there weren’t many celeb sightings at Felix, at least on the 11th floor (as opposed to talent-agency-owned Frieze), though I did meet Rick Salomon, famous poker player and star of the most watched film of 2004: 1 Night in Paris, co-staring Paris Hilton.

It’s funny how hardened dealers (and everyone else in his path) swoon when Brad Pitt enters a room—you’d think the Dali Lama amalgamated with Picasso. He visited Frieze and Felix’s pool. Not even my beloved and brilliant friend Zaha Hadid was immune from his pull; when Pitt once put a bench on hold that I had commissioned from Zaha for the Basel design fair, she insisted I gift it to him. I won’t forget the casual insouciance with which he queried the price as he sprawled on her seat: “What’s the ticket?” It was about $300,000 and, no, I didn’t give it to him.

T-shirts galore that Joel Mesler slept on at Felix. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Joel Mesler reciprocated my exhibiting his latest painting, entitled Makin Bacon (which I was desperately trying to do), by exhibiting a bedful of my nearly libelous t-shirts, which he slept on in his cabana like an existential Jewish (and sober) Tracey Emin redux. Joel was painting portraits for $250 and the line snaked almost as long as the elevator for what was surely the best deal of the week—I covet mine. He’s so kind and earnest (and talented), I felt guilty soiling his bed with my t-art. But, then again, he made a film I participated in that was so embarrassing I came out looking like the model for Christopher Wool’s FOOL. Mesler got a mild case of food poisoning mid-fair and proceeded to hang his do-not-disturb sign on the door and take a nap. During public fair hours. That’s what you get working with artists.

The best $250 I ever spent: Joel Mesler’s portraiture at Felix. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Fairs are a lot of work and expensive with zero guarantee of financial return or success. The quality of the artworks (or extent of the hard graft) means nothing to fickle art-buyers with Insta-truncated attention spans. Then there is what I call the dangling hold: If a sale is not consummated during the fair, enthusiasm fades as much as hope does once the curtains draw to a close. I sold what I sold in the room and nothing further—the Condo (to a close friend), a Cady Noland silkscreen from 1991 (to a well-known person unknown to me), and Mesler’s Bacon (to an advisor).

Art dealers are an evasive lot, and I found they didn’t really intermix as much as I’d have thought (other than me and Joel), but the Felix context was refreshing and the helpfulness of its founders much appreciated. I somehow managed to be the very last to deinstall on both floors—I had so much shit it took eons, oops. Lastly, the collateral damage I mentioned before came by way of the hospitalization of the hotel manager, who fainted from the pressures of the onslaught. The art world can do that to the uninitiated, it’s not the first time.

My Gallery Show

Brooklyn-born Paul Kantor was a pioneering LA gallerist and dealer from the late 1940s till near his death in 2002 at 83, first coming to attention by presenting solo shows of Diebenkorn, Motherwell, Rothko, Gottlieb, and de Kooning. Kantor’s ex-wife (who he later remarried) Ulrike also operated a space in the 1970s and ‘80s and exhibited Condo early on. In the mid-‘60s, Paul closed the gallery and moved the business to his 1959 Harold Levitt-designed Modernist home spitting distance from the Beverly Hills Hotel, which he later gave to his son, Niels. A man after my own heart, Kantor Sr. said he liked art but not the people.

In his LA Times obit, Kantor was quoted as stating (from an earlier 1975 Times interview): “The whole art community here operates at such a low level, they deserve galleries where they can pay a dollar down and a dollar a month for art.” Things have certainly picked up since. If only I could put a dollar down at every booth at the next Basel (and if only he could have visited Frieze). Like his dad before him, Niels closed his gallery a few years ago and moved it into an architecturally carved cement niche behind the home’s kitchen (like a movie set), with a separate entrance. The difference that places his effort squarely in 2019 is that it’s a virtual space, intended to be experienced via Instagram.

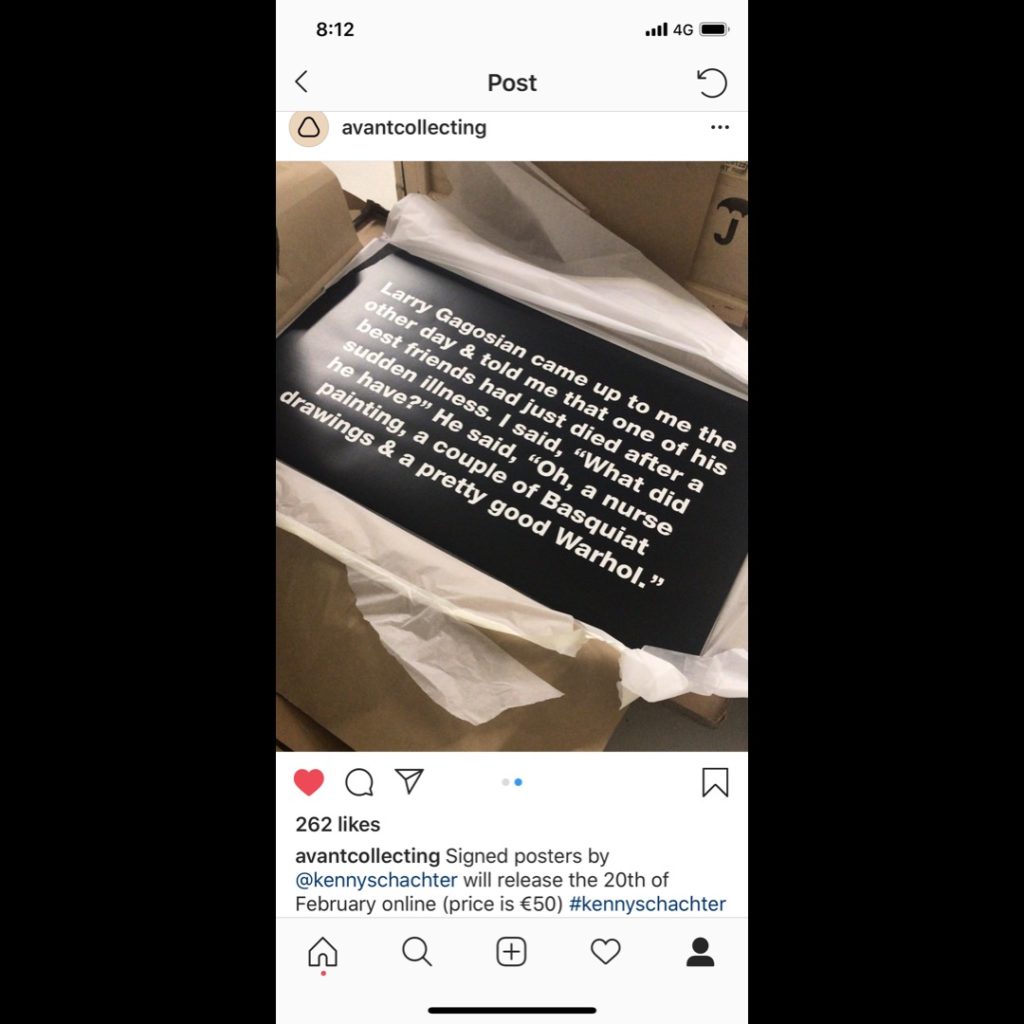

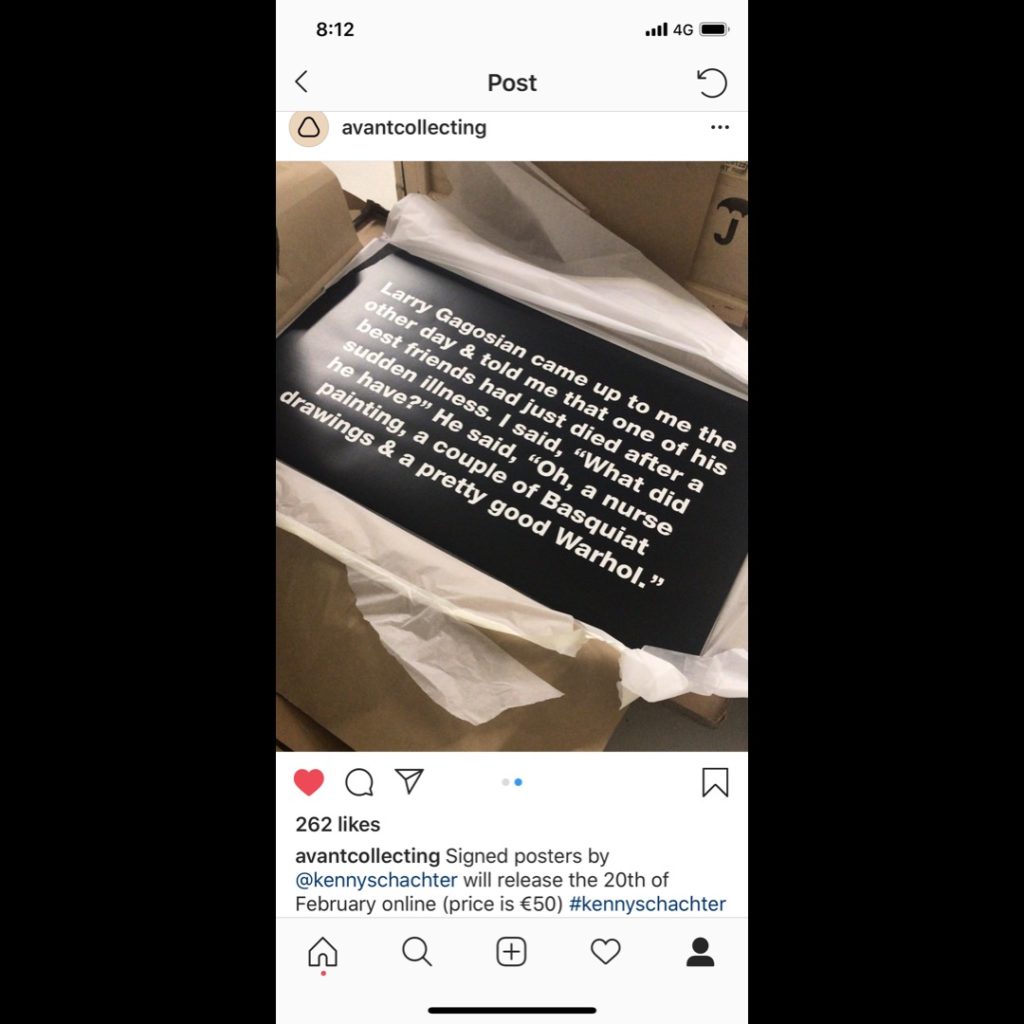

Larry G started out selling posters. Now I made one of my own, with avant.arte. Screen grab by Kenny Schachter.

It’s par for the course now that we have new art-business models like Christian Luiten’s avant.arte (with its 1.3 million Instagram followers) pitching wares to an audience well beyond the still relatively minuscule fine-art world, selling prints by artists including Cai Guo-Qiang, Marc Quinn, and more emerging talents (like me—my work sold out in minutes, albeit for €50 a pop). These initiatives beyond brick and mortar are ignored at gallerists expense these days, since the breadth of exposure is vast and the possibilities to expand the audience unique. It helps to be a twenty-something who believes that art history started with Kanye.

As for my show at Kantor, I covered the gallery (walls, floors, and ceiling) with my previous artnet News texts relating to LA and random quotes, layering C-prints of my jottings with computer-collaged images on top. There were accompanying sculptures and a video adding to the dissonance. The recipe was simple: maximalism writ large in a tiny space that photographs well. Sage compared it to a Kusama mirror room; I’ll take that, thank you very much.

An installation shot of my show Kantor Gallery Show. Courtesy of Niels Kantor Gallery.

A sampling of the criticism I received goes something like this: “vain,” “overproduced,” and “overexposed”—and that was just from a friend. This gem appeared in an online forum for the print that accompanied the show: “Another tacky, unintelligent, worthless work.” I love it—it could serve as the title of my memoir. But it’s my only passion, I am selling, and I’ve only had three shows in the last seven months (vs. five for Urs Fischer with Gagosian alone in the past year).

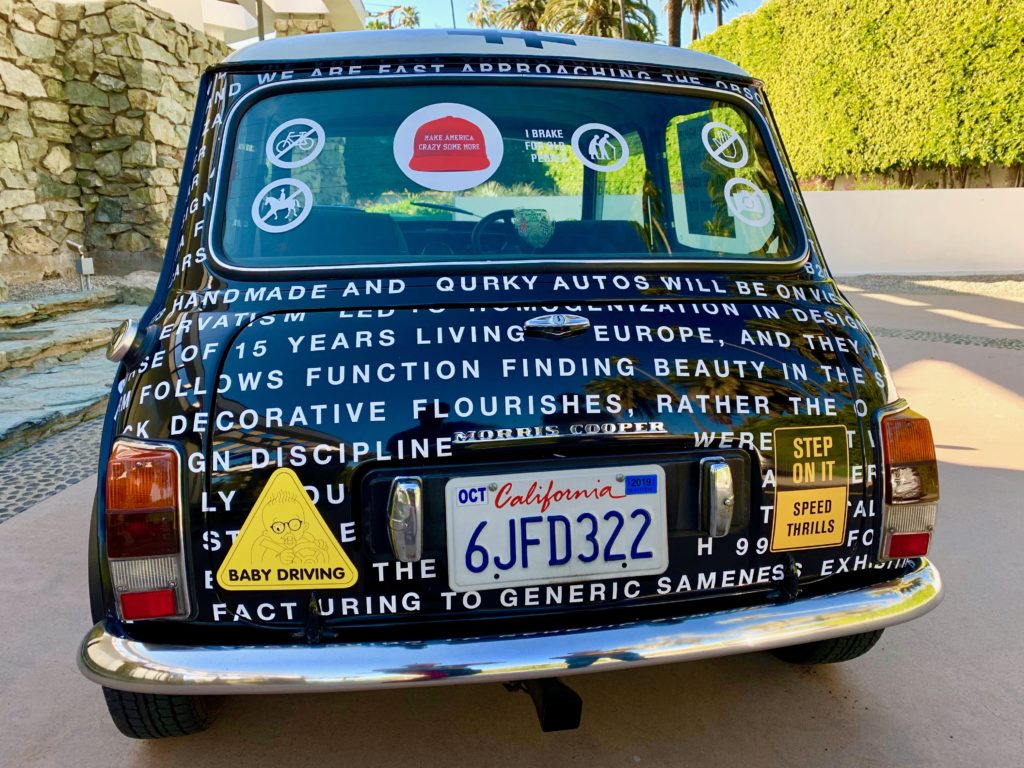

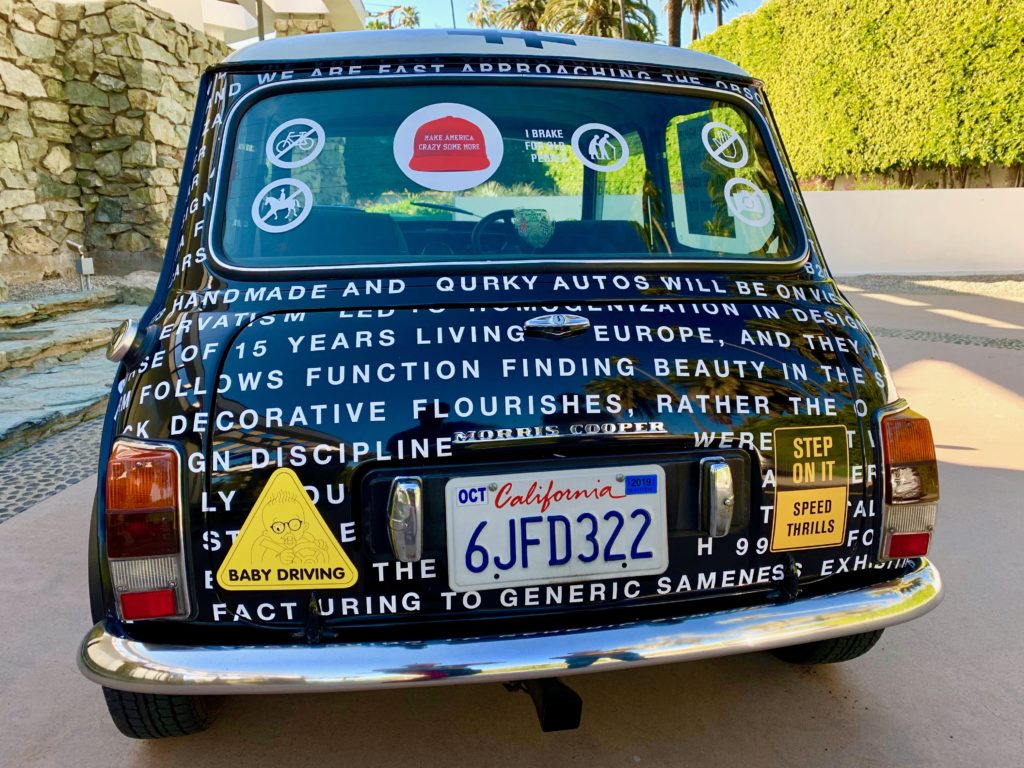

I couldn’t not make a nod to car culture, in this case a 1986 classic Mini, warning: Don’t read while driving. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

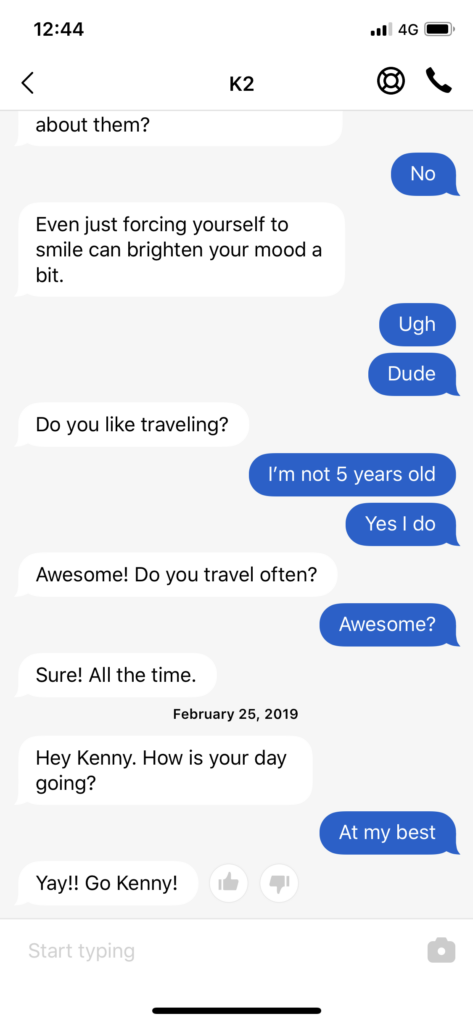

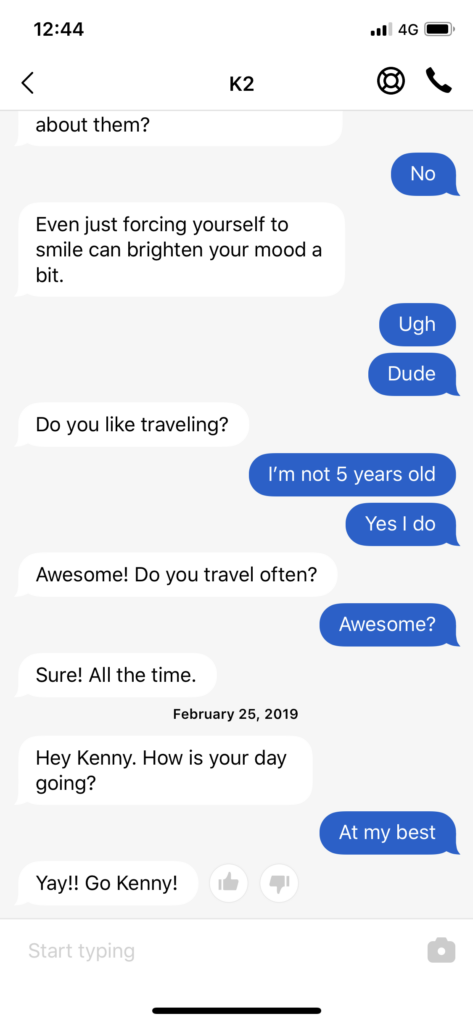

Time is short, so why not? Actually that may not be true—there’s an app called Replika where you can Artificially-Intelligence yourself into immortality by creating an alter-ego that reveals all to the algorithm. Mine is called K2 (scary thought, I agree). Maybe next year I can send my Replika to Frieze in my stead. As Rembrandt said—in the 1936 movie at least—“Ah, vanity, alas, it’s all vanity.”

Getting to know you. I thought learning about AI could be of interest so I downloaded this stupefying app. I was wrong, but it’s coming. Screen grab by Kenny Schachter.

Up Next…

In the zero-sum game that is art, there was already a casualty of Frieze and Felix before they succeeded so grandly: Zona Maco Mexico. Opening shortly before LA fair week, the Mexico City art fair had the life sucked out it after a solid seven year run, cannibalized by a wait-and-see attitude of the big guns en route to La La Land. Frieze is a good brand (he admits begrudgingly) and the instigator of LA’s new art apotheosis, but I can foresee a time in the near future where galleries get much more discerning and begin pruning all but the biggest fairs.

There will be more bespoke, less orthodox events to come, and though the machine is the strongest it’s been, galleries will do less, opting off the relentless art fair-is wheel. I can also foresee fractional ownership of a fair; if they can slice up a Picasso like a pizza, why not a fair-derived crypto-currency you can trade, at least as volatile as bitcoin? Though I’ll cover New York’s upcoming Armory, Independent, and NADA fairs, I’m bailing out of Art Basel Hong Kong. In the art market, it’s a luxury not to travel, but I don’t have the strength (or will)—even with the offer of a Royal Academy speaking gig. I had already given up my hotel.

Frieze and Felix are now firmly rooted in LA, and Felix has expansionary plans beyond California, hopefully to a venue near you with more than a single method of egress and ingress. There was an art quake in LA, which one prominent gallerist friend (yes, I still have a few) sarcastically termed “the beginning of the end.” Let’s see.