Opinion

Snow, Schlag, and Schnabel: Kenny Schachter’s Dispatch From St. Moritz (and Predictions for 2018)

With the money as vertiginous as the alpine peaks, art is on everyone's mind in the Swiss mountain village.

With the money as vertiginous as the alpine peaks, art is on everyone's mind in the Swiss mountain village.

Kenny Schachter

I’m no fan of Christmas, New Year’s is even worse—all the contrived peace, love, and joy is frankly too much, not to mention the practice of holiday emails that amount to spam worse than any scam to steal money from unsuspecting galleries doing business in China. Sorry, I’m off-piste already. I have been visiting St. Moritz, the Swiss Alpine village, with my avidly skiing family for 25 years. From the suburbs of Long Island, I have always been at best an anxious and hesitant winter sportsman, even before Sonny Bono, Michael Kennedy, and Michael Schumacher tragically met their fate on unforgiving slopes. Personally, I prefer the pre- and après-ski to the part that comes in the middle.

Thankfully, there is a rich history of artists frequenting the region, and more galleries per square foot than in any resort worldwide—the closest competitor being the seaside town of Knokke, improbably referred to as “Belgium’s St. Tropez.” At 15,000 and 16,000, respectively, the populations of St. Moritz’s Engadin valley and Knokke are remarkably similar: both boast a history of illustrious artist inhabitants, with Giovanni Giacometti (and family), Giovanni Segantini, and Gerhard Richter in St. Moritz and James Ensor, René Magritte, and Paul Delvaux in Knokke (where Magritte and Delvaux painted the casino); each features between 20 and 30 commercial exhibition spaces.

I’ve never had the kismet to visit Knokke (yet), but I can attest to the depth of quality of the art experience in Switzerland’s largest and easternmost canton of Graubünden, which encompasses St. Moritz. A far cry from ordinary, some of the galleries in the adjacent municipalities of Zuoz and S-chanf are housed in astonishingly picturesque structures dating from the 14th century—reason enough for a visit. More remarkable than the historic architecture is the thriving art scene; the dedication and intensity of the proprietors and visitors alike compensates for their relative paucity in numbers, though I’d wager that in the middle of St. Moritz, due to its central location, the audience figures are better.

Out for a casual stroll in St. Moritz. (Photo by Scott Barbour/Getty Images for St. Moritz Polo Club)

By nature of the inaccessibility of the Engadin—geographically and economically—there is nothing bashful about the privilege on display, obnoxious enough to embarrass a peacock. From men (and children) in the furriest full-length furs, endangered no doubt, to dogs dressed better than me (ok, that doesn’t take much), this is a freak show beyond Lucas’s Mos Eisley bar in Star Wars. The exorbitant expense of St. Moritz will never abate, and ensures the place won’t open up anytime soon—unless you are filthy rich, of course, and then lo and behold, all prejudices fall by the wayside. (Save for gaining entry to one of the private clubs that are all but closed to most races and religions, including mine, but that’s probably better left unsaid.)

Badrutt’s Palace Hotel. Image courtesy of Badrutt’s Palace Hotel.

Opened in 1896, Badrutt’s Palace Hotel—and in particular Mario’s bar located within it—is the nightly congregation point for the good, bad, and ugly (often embodied in the same person). As an aside, the hotel was the site of one of the most egalitarian acts of generosity recorded: in 2006, its childless owners, Hansjürg and Anikó Badrutt, bequeathed a two-thirds share to the then managing director, Hans Wiedemann.

Smoking in Mario’s is not only allowed but encouraged—fat, stinking cigars especially, which are consumed by men, woman, and kids alike. When the sliding doors of the bar close, it’s like surfing a cumulus cloud, or being locked in a hotbox of tar and nicotine. Granted it’s gross, but in today’s intolerant universe there is something to be said for the freedom of choosing your poisons, and then fully bathing in them. My last drink of the evening, for instance, is the same as taking one final ski run—better left undone, as that is when you’re most prone to accidents. Trust me. No identification is required for (underage) alcohol consumption, and the resultant tyro-like behavior is commensurate with such libertinism; among the worst I witnessed was a noted young art-worlder spitting phlegm into the carpet and then grinding it into the floor with his shoe. You can’t buy manners (or empathy).

Taking my daily sprightly alpine walk up the mountain one morning, I bumped into Lord Norman Foster, architect of Chesa Futura, the apartment complex where he resides in St. Moritz with his wife Elena (founder of artists’ book publisher, Ivory Press) and family. The building, shaped like a kidney bean, was constructed in 2004 with 250,000 shingles individually hand-cut from indigenous trees by three generations of the same locally based family. The majestically aging design is half-singed where it is exposed to the elements, and honey-colored beneath. A fellow car enthusiast, Foster is organizing a museumwide auto exhibition with the full run of London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 2019. Vroom!

Norman Foster’s Chesa Futura, 2004. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Before you pillory me for luxuriating in the snowy lap of the 1 percent (of the .01 percent), the other side of the coin (literally) in St. Moritz is the art, of which plenty abounded. There was even the perfunctory charity auction, featuring two of my sons, Adrian and Kai, organized by local twenty-something resident Henriette (Popy) Leimer-Lefort of Allegra Projects to benefit the extracurricular school programs of low-income children in St. Moritz (as hard as that is to fathom). Successful though the event was, a note for the future: please replace the anemic auctioneer from Christie’s Zürich, who could have lulled a raging crackhead into hibernation.

Lucio Fontana’s Concetto Spaziale, Quantas (1959-60) as seen via Robilant + Voena’s super solicitous, personalized customer service. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Robilant + Voena of Milan, London, and St. Moritz, in its fourth year of operation in the valley, sold two works in its group show featuring market stalwarts Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana, and Enrico Castellani. What I found more eye-opening were the less familiar works of Franco Angeli (1935-1988), a member of the Scuola di Piazza del Popolo together with Francesco Lo Savio, Mimmo Rotella, Giuseppe Uncini, Giosetta Fioroni, Mario Schifano, and Tano Festa. These Pop-infused works from the 1960s and onward were rawer than their American counterparts, more ostensibly engaged with sociopolitical and economic concerns. Drugs, rock music, and womanizing were part and parcel of the mantra fueling the group and probably went a long way to curtailing further international successes for the artists. Can’t have it all.

Improvising some depth behind an early Fontana slash (made before the artist started doing so himself) at Robilant + Voena. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

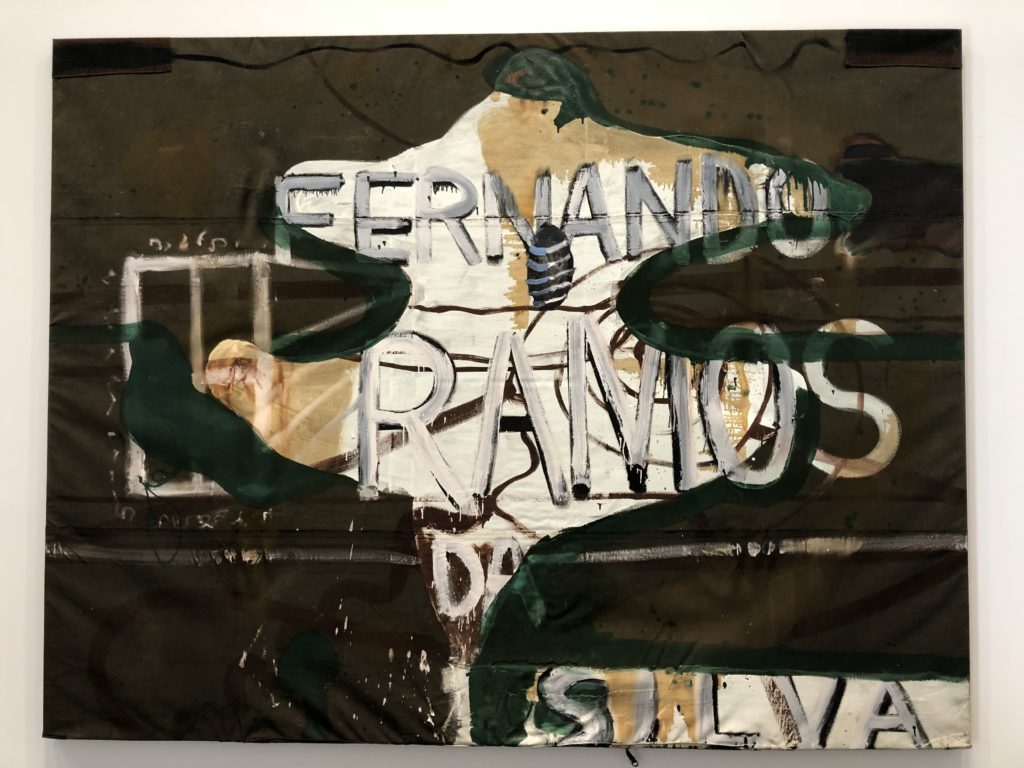

The gallerist Andrea Caratsch featured paintings and sculptures by Julian Schnabel, who’s become a symbol of the area’s artiness since he first appeared in St. Moritz under the tutelage of legendary dealer Bruno Bischofberger in the 1980s. Prices for paintings and sculptures ranged from $300,000 to $1,400,000, mirroring Schnabel’s recently recorded auction record. When it comes together, as in the vivid text-based painting entitled Fernando Ramos da Silva, Julian is a narrative painter of imaginative force. His work is looking a value, watch.

At Galerie Andrea Caratsch: Julian Schnabel’s 1987 work Fernando Ramos da Silva. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Vito Schnabel, occupying his godfather Bruno’s former gallery, presented a series of works by Dan Flavin from 1990 dedicated to Austrian potters Hans Coper and Lucie Rie. The Flavin works were unorthodox (for the artist), inasmuch as they were anthropomorphized versions of his representative light fixtures, assembled into shapes resembling crude robotic forms like Joe Bradley canvases. Priced at $275,000 to $325,000, the light sculptures were from an edition of five and invited conjecture among the vacationers as to what was posthumously fabricated.

Dan Flavin’s untitled (to Hans Coper, master potter) (1990) at Vito Schnabel’s gallery. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I liked the pieces very much, but a late-dating manufacture could determine their (lower) present asking price and weigh against future value; it’s always a tricky question. The most egregious example of such beyond-the-grave industriousness (besides the Yves Klein “Venus” sculptures at Gmurzynska in town) is Constantin Brancusi, who appears to have had his most prolific year in 2017. (It’s only a matter of time before he hits the slopes in St. Moritz.)

Kenny Schachter and Vito reflecting on Schnabel’s fab Dan Flavin show. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

In the slightly outlying Zuoz and S-chanf is von Bartha Gallery of Basel, exhibiting tasteful abstract paintings by “shooting star” Landon Metz (who also exhibits at Sean Kelly in New York). I profusely thanked the affable proprietor Miklos von Bartha for his time touring me through the space, to which he replied: “I am grateful someone is interested in visiting an art gallery.” He went on to relate how he previously decided to remain open deeper into the season, only to have a grand total of 11 guests in a month, six of whom were related to his gallery assistant.

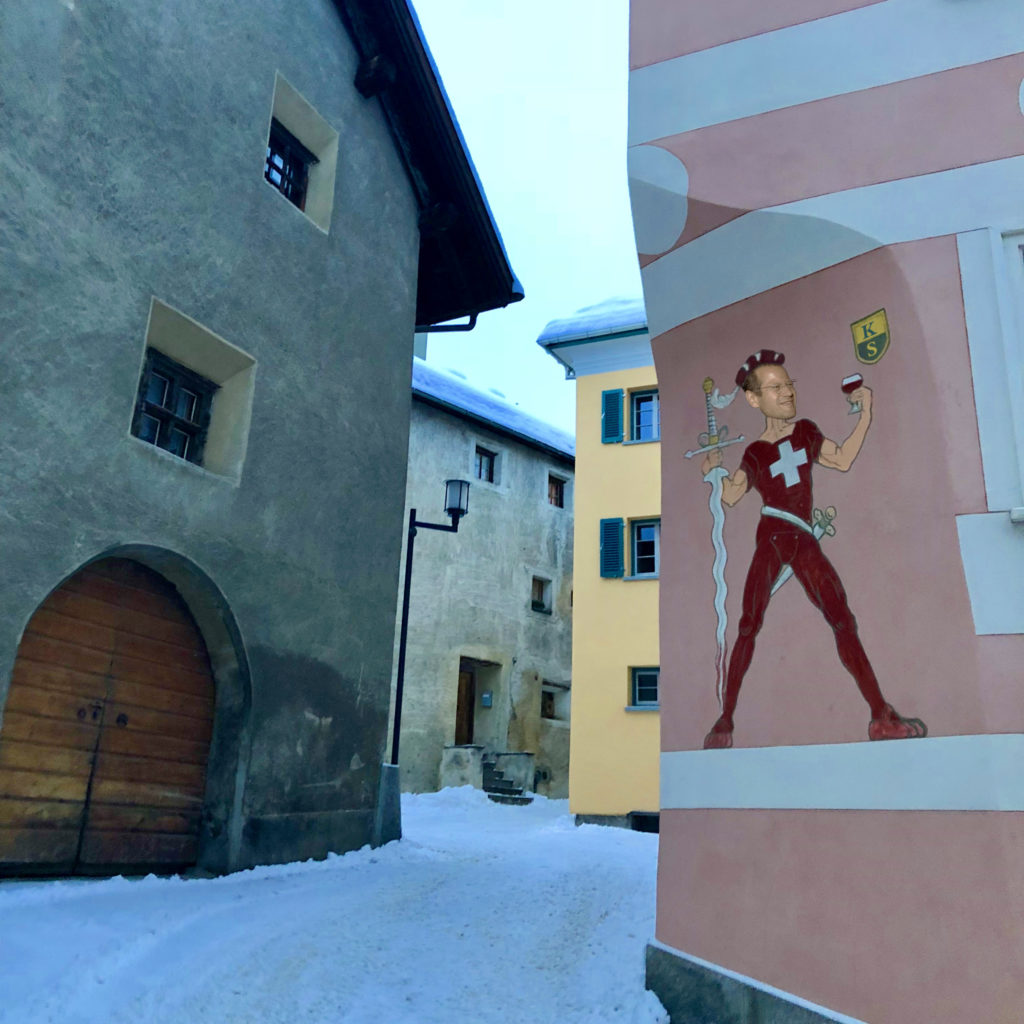

Zuoz, Switzerland. As odd as it is, it’s gallery land. Irreverent photo illustration by Kenny Schachter.

Galerie Tschudi—their only gallery is in Zuoz—is open year-round, and its ancient exhibition space and barn may very well be the most extraordinary gallery I have ever seen. The Richard Long room, situated in an old hay barn that is exposed to the elements via a series of irregularly shaped wooden slats, blurs inside and outside, letting in light (and the freezing cold).

Richard Long in the hay barn at Galerie Tschudi in Zuoz, half indoors, half out. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Happening upon the Swiss-born Niele Toroni’s (b. 1937) wall paintings at Tschudi was like seeing something peculiarly familiar for the first time. It’s amazing how aesthetic forethoughts could be transformed: I fell for the cheerful abstractions made by imprinting marks from a Number Fifty paintbrush at perpendicular intervals of 30 centimeters (to each their own) as if for first time. Toroni started the group BMPT (art group) together with Daniel Buren, Oliver Mosset, and Michael Parmentier, and with an auction record of $162,500 last May look for further increases in the near future. Artists today seem to have abandoned the notion of forming groups altogether, but a fun one might consist of Damien Hirst, Jeff Koons, Urs Fischer, and Anish Kapoor—I’d call them “The Producers.”

Niele Toroni’s uplifting wall painting at Galerie Tschudi in Zuoz. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

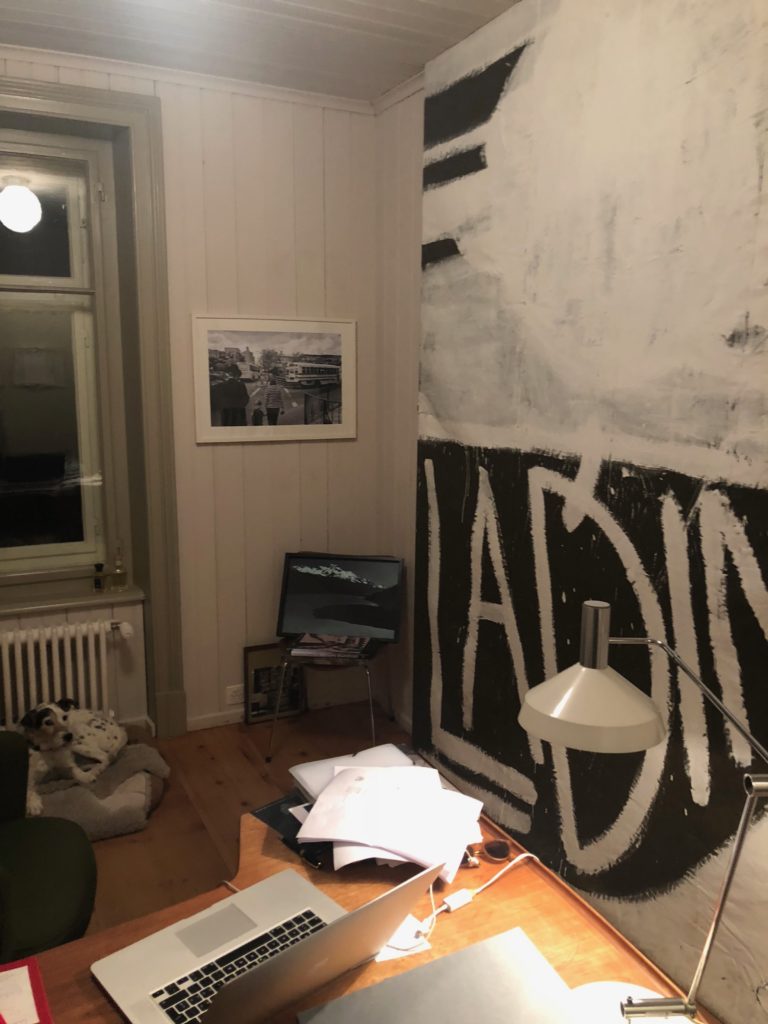

Villa Flor is the cutest, coziest seven-room hotel on earth. Now in its eighth year, it was started by Ladina Florineth, a former ski instructor who’s mountain-guide father died in an avalanche 35 years ago. Turned onto art by his client Bruno Bischofberger, the Florineth family was hooked and the hotel is dominated by a who’s who guest roster of contemporary artists, dealers, and those who crop up in between. Like when the lawyer of a major artist’s estate stuck his head out of the bathroom and snapped at me: “I should have kept the door locked.” (He’s a friend and was kidding—I think.)

From someone who kind of shied away from Schanbel paintings past, I became an unabashed fan viewing a work loaned by Bischofberger that didn’t quite fit into Ladina’s office—prompting her to do what any enthusiast worth their salt would do, which is to cut a hole in the ceiling and shoehorn it into place. Fearful of Bruno’s reaction to the unorthodox installation, Ladina was relieved when he saw the work and replied, “Perfect,” so there it remains, melded organically into the space.

Julian Schnabel’s Ladin shoehorned into the micro arts hotel Villa Flor in S-chanf. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Being in art today is like being a doctor in a hypochondriac ward: everyone nervously wants your opinion about what’s going to happen next. The only thing people are more preoccupied with than prices and the anointment of the next art star is an explanation of Ripple, the latest rage in cryptocurrency speculation. (When will auction houses, if ever, accept this stuff?) Though gallerists have been said to be under nothing less than a siege, I found the practice alive and well in the Engadin, where it’s about nothing less than time and passion—and there is a blizzard of both in this region. Obviously, reflecting the profile of the typical art-viewer, there was a noticeable shortage of nonwhite, nonmale artists and patrons; but I can see it changing, albeit at as slow a pace as one of the 173 glaciers nearby.

As far as obligatory prognostications for the coming year, I’d say look for the same but (lots) more: the further proliferation of fairs, the expansion of art as a luxury lifestyle, China’s voraciousness to collect and open private museums, and Instagram’s ever-expanding art (market) impact, all continuing to shape things as never before. By default, Instagram upended hierarchies as if we collectively pulled down our pants showing all to all, and that it’s willful makes it more fantastical—a Warholian wet dream. In the process, age-old barriers to enter art, reserving it (predominantly) for the secluded purview of the St. Moritz crowd, have been obliterated. Our appetite for price porn will only swell, but art is more inclusive than I can remember in over 30 years.

A living in art has never been easy, nor will it be. Connoisseurship and enthusiasm versus the (ruthless, backstabbing) market for art are parallel universes that on occasion collide but, more often than not, don’t. On a walk just prior to New Year’s, a gentleman of advanced years fell onto the ice, directly impacting the crown of his skull—and couldn’t get up. His significantly younger blonde companion, sensing the premature end of her evening (if not worse), retorted: “Christ, I turn my head for five minutes and look?” I flagged down a car to take the man to the hospital and, with the assistance of another woman passing by, helped him into the vehicle. I immediately thought to ask the victim’s girlfriend if she might consider a career as an art dealer.