Opinion

How Did Leonardo da Vinci Become So Famous? 500 Years After His Death, a New Book Offers Some Intriguing Answers

The authors of 'The Da Vinci Legacy' make a case for an alternate reading of history.

The authors of 'The Da Vinci Legacy' make a case for an alternate reading of history.

Jean-Pierre Isbouts &

Christopher Brown

A lot has been written lately about today’s iconic status of Leonardo da Vinci, particularly since this year is the 500th anniversary of his passing. But how did Leonardo get to be our Renaissance pop icon? After all, the artist died in relative obscurity, exiled in France, while overshadowed by his rivals Raphael and Michelangelo. True, much of the Da Vinci mystique was sustained by two seminal paintings—the Last Supper fresco in Milan and the portrait of the Mona Lisa—but how exactly did that happen? For example, the Mona Lisa hung in Fontainebleau Palace in France, not a place open to the public, while the Last Supper fresco had by the mid-16th century become “a ruin,” to quote Giorgio Vasari.

In our book, The Da Vinci Legacy, we try to unravel that mystery without pulling any punches. Among others, we must take Walter Isaacson’s otherwise commendable da Vinci biography to task for perpetuating the fiction that Leonardo left Florence for Milan on behalf of Lorenzo de’ Medici, the de facto ruler of Florence. This was clearly not the case, for in this instance Isaacson fell victim—like so many other authors—to the skillful propaganda of Duke Cosimo I. Elsewhere, we identified many factors of Leonardo’s enduring renown that are not often addressed in art history books, such as the role of political currents in Italy and France, and the strong reaction against sacred art—and the Church altogether—in the wake of the French Revolution.

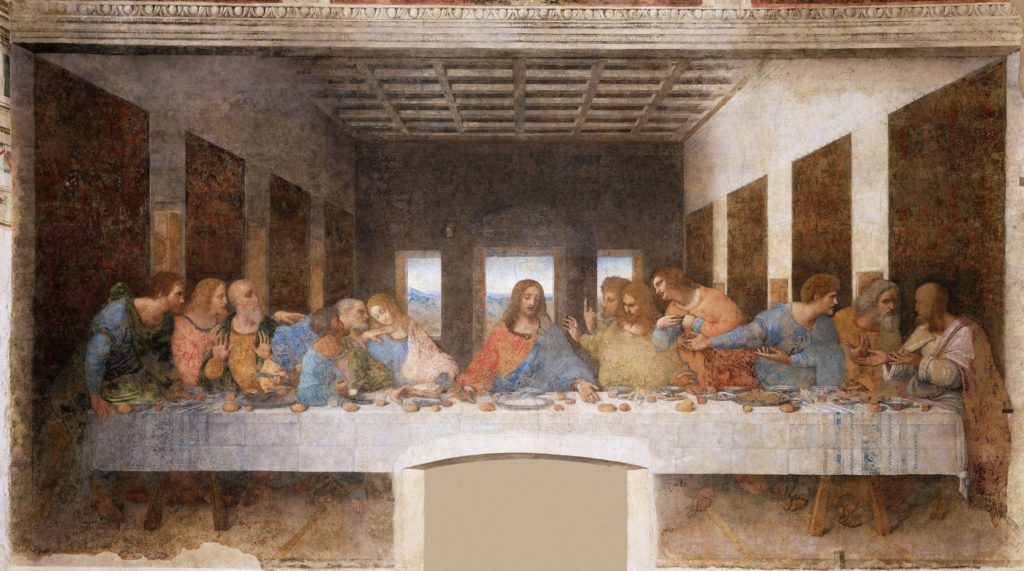

This macro view of looking at art through the prism of social and technological change can produce new and intriguing data. For example, we found that the fame of the Last Supper was due in no small measure to the rise of the first reproducible mass medium: the copper engraving. The sheer monumentality of the Last Supper fresco, and the relative absence of optical effects and detail, made the work uniquely suited for this (largely linear) medium. As a result, we believe (also citing the work of Leo Steinberg) that the Last Supper was the first work of art to enjoy broad distribution throughout Europe, as many prints from the era attest.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Last Supper.

But perhaps the most interesting finding is that time and again, Leonardo da Vinci’s mystique became a convenient device for autocratic rulers to boost the legitimacy of their regimes. A key example is the previously cited myth that Leonardo was somehow dispatched to the Sforza court of Milan by Lorenzo de’ Medici. The opposite is true. Leonardo never enjoyed the patronage of the Medicis, because unlike his rivals in Florence he was uneducated and unlettered, unable even to write or read Latin. What’s more, he had been denounced (in the form of an anonymous letter deposited at city hall) of having sex with a 17-year old boy, the goldsmith-apprentice Jacopo Saltarelli. Officially, sodomy was still on the books as a capital offense, so this certainly didn’t help Leonardo’s reputation in the circle around Lorenzo the Magnificent.

But this situation changed in the 16th century, after the Medicis had forcefully toppled Florence’s democratically elected republican government and installed an autocratic duchy. Knowing that this coup was deeply resented by the merchant class, Duke Cosimo I initiated a propaganda campaign. Its objective was to stress the role of the Medicis as the founders the glorious Florentine Renaissance in the Quattrocento. Two loyal Medici clients, the so-called “anonymous Gaddiano” (in reality Bernardo Vecchietti, an official at the Medici court) as well as the artist and author Giorgio Vasari, dutifully advanced the fiction that Lorenzo sent Leonardo to Milan as a token of the Medici’s generous patronage. In reporting this myth, however, they confused the motive: Anonimo says that Leonardo was to present a lyre to the Duke to be played by the musician Atalante Migliorotti, while in Vasari’s book the roles are reversed: it is now Leonardo himself who is renowned for his performance as a lyre performer. Perhaps they didn’t read the fine print.

For the next two centuries, Leonardo’s reputation was sustained by the continuing demand for copies of the Last Supper and the Mona Lisa, but by the 18th century that practice had largely ceased. This is the moment when Leonardo’s legacy could have faded away, in part because the influence of Italian art itself suffered a rapid decline. But then, an unlikely source—the absolutist monarch Louis XVI—came to his rescue. Knowing that the French court had three of the artist’s most important works except for the Last Supper, the king ordered a major effort to produce a detailed reconstruction of the mural in Milan—mere months before the outbreak of the French Revolution. He also initiated the idea to house the royal collection in a national museum—which would become the Louvre—even though this is usually credited to the revolution.

Jean-Pierre Isbouts and Christopher Brown’s new book The Da Vinci Legacy.

After Napoleon (who hung the Mona Lisa in his bedroom) was defeated in 1815, the European powers wondered what to do with the government in France. They decided to restore the monarchy by foisting the shockingly obese Louis XVIII on the throne—a deeply unpopular move. In response, royal commissions went out to several artists (including Ingres) to rush out paintings and prints, depicting Leonardo passing away in the arms of King François I. What better way to express the innate compassion of the French monarchy? It wasn’t true, of course—François happened to be in St.-Germain-en-Laye when Leonardo died—but no one wanted the facts to get in the way of a good story. From that point on, preserving the legacy of Leonardo became a predominantly French affair—abetted by stunning new steel engravings of the Mona Lisa, published in the second half of the 19th century.

And finally, in 2017 another absolutist monarchy—that of the House of Saud—acquired at auction a presumed Leonardo autograph, a portrait of Salvator Mundi. Imagine the irony of a ruler of the strictest Islamic nation in the world, where public Christian worship is outlawed, paying nearly half a billion dollars for a portrait of Jesus Christ.

Not only did we examine the political ramifications of Leonardo’s oeuvre, but we also investigated the work of Leonardo’s pupils—the so-called Leonardeschi—and conclude that Paolo Giovio’s 1527 verdict is correct: the master “left no student of any fame.” Worse, Leonardo’s breakthrough discoveries such as the use of sfumato and his dramatic chiaroscuro were avidly imitated by others, notably del Sarto and Correggio, obviously without any attribution. And to top it all off, his notebooks on science and anatomy—which in themselves could have revolutionized the practice of medicine at the time—were not published until the late 19th century. Thus, we conclude, it is perhaps a miracle that Leonardo’s fame did not disappear into the mists of time but rose to become the pre-eminent Renaissance icon of the 21st century.

Dr. Jean-Pierre Isbouts is a humanities scholar, best-selling author, and award-winning filmmaker, specializing in Near East archaeology and Renaissance art. A doctoral professor at Fielding Graduate University in Santa Barbara, California, he gained worldwide renown with his 2006 book, The Biblical World, which became an international bestseller and is now in its fourth print. This success led to a series of National Geographic books, including the bestsellers In the Footsteps of Jesus (2011) and The Story of Christianity (2014). Dr. Christopher Brown is the director of Brown Discoveries, LLC in North Carolina, devoted to studies of Renaissance art. The two scholars also collaborated on The Mona Lisa Myth, 2013 and Young Leonardo, 2017.