Art Criticism

‘All the Beauty and the Bloodshed’ Is a Truly Great Artist Documentary. Here’s What Makes It Work So Well

The film, which explores the life of Nan Goldin, is directed by Laura Poitras.

The film, which explores the life of Nan Goldin, is directed by Laura Poitras.

Ben Davis

All the Beauty and the Bloodshed doesn’t really need more praise. At this point, I probably don’t even need to introduce this beautiful and harrowing documentary, which tells the story of the life, art, and activism of photographer Nan Goldin.

It won the Gold Lion at the Venice Film Festival, the second-ever documentary to do so. It was nominated for an Academy Award (which it lost last Sunday to Navalny—not a better film, though one that likely felt more topical to Oscar voters). In theaters it has received reviews that range from good to glowing, and it is set to stream on HBO next week.

And yet, despite all the attention it’s received, I think it’s instructive to ask why Laura Poitras’s film works as well as it does.

After all, the recent past has produced an excess of documentaries about artists. Indeed, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed can be looked at as a hybrid of the two main types of contemporary art documentary: monographic “lives of the artists” pieces like Sky Ladder: The Art of Cai Guo-Qiang or Hilma af Klint: Beyond the Visible; and more issue-driven, newsy docs focused on issues around the art world, like The Lost Leonardo or The Price of Everything.

Nan Goldin and Laura Poitras attend the 95th Annual Academy Awards on March 12, 2023 in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Jesse Grant/Getty Images)

This is a deliberate decision by Poitras, who turned a more directly news-focused documentary that was already underway by activists, chronicling the Sackler P.A.I.N. movement, led by Goldin, into something that digs more deeply into her personal story. At different moments, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed feels like different films. Sometimes, it fixes on the present-day intrigue of efforts to hold the Sackler family accountable for its role in stoking the opioid crisis; at other moments, it is a careful, sensitive account of the experiences that informed Goldin’s famous photo works.

This shapeshifting quality makes for a low-key odd structure—but the oddness is, as far as I am concerned, the first strength of the film. It gives it texture. It cuts against the flattening effect of most artist biodocs into tales of creative striving and empowerment, with talking heads deployed to state out loud why the work is important—against the “PBS-ification” of artists.

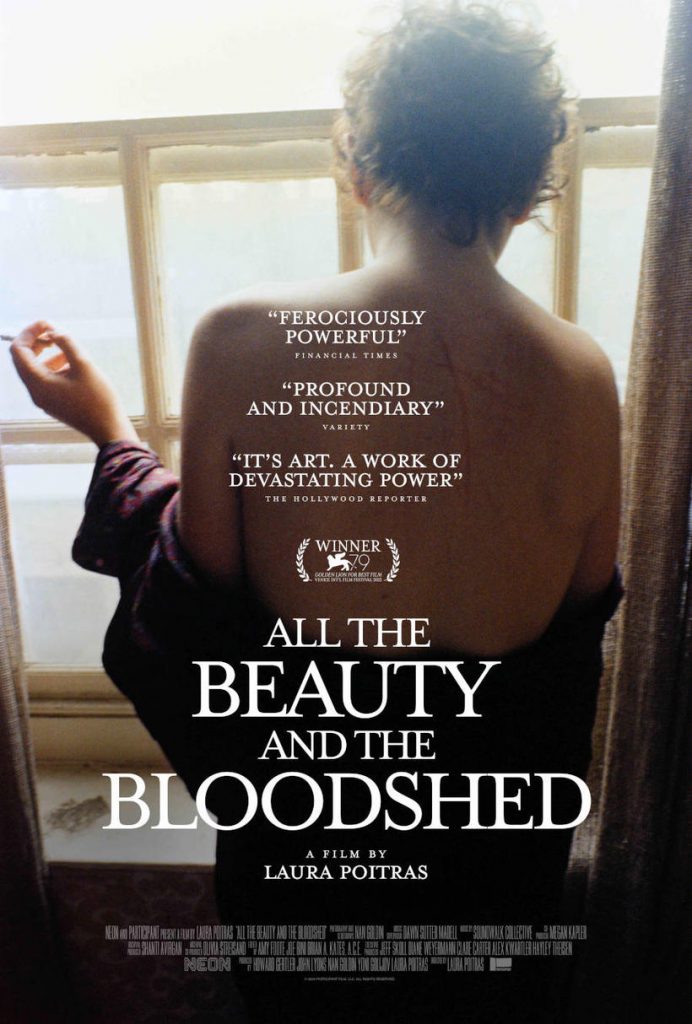

Poster for All the Beauty and the Bloodshed.

Without exactly synthesizing, these two currents do set each other off and deepen each other. Normally, the question an artist biopic sets out to answer is just “why is this person so interesting to people?” From the point of view of engaging us with Goldin’s biography, starting with the present-day protests provides a much more specific and compelling direction. It feels as if we are solving a mystery in re-visiting the incidents of her life: the mystery of how this well-known artist ended up spending her mature career protesting the museums that carry her work, and the Sackler name.

From the other point of view—the point of view of a documentary about Goldin’s P.A.I.N. organization (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now) and the broader reckoning with the roots of the opioid crisis in America—Goldin’s personal narrative serves as the vehicle to understand the human stakes, beyond the statistics. But, again, putting it that way is a little too pat for what you see in the film. You do hear her talk about her own overdose, but as laid out in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, Goldin’s biography is not reduced to material invoked to explain the circumstances of addiction or even to explain the rage and empathy that drives her organizing with P.A.I.N.

And I think, rhetorically, that’s important. Paradoxically, there’s a certain kind of deadening effect when hardship narratives only appear to “mobilize empathy” or provide backstory for a present-day news hook. As far as I am concerned, the fact that Poitras makes it so that the biographical narrative doesn’t quite fully resolve with the activist one actually makes it cut deeper.

A photo from Nan Goldin in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed directed by Laura Poitras. Photo courtesy of Neon.

The second thing that gives All the Beauty and the Bloodshed an unusual staying power for me has to do with Goldin’s art itself as a subject.

Goldin’s photos are, of course, already substantially autobiographical. Their value has always been bound up with a certain accounting of her social scene, from her early depictions of Boston drag shows to her images of the downtown demimonde in New York. And so Poitras’s documentary organically works to enrich and amplify what made the art special and worthy of attention in the first place. (As the film recounts, the diaristic quality of Goldin’s art is what made it stand out in an ’80s photography world that still prized a more rarified style of black-and-white formalism).

But it’s not even just that Goldin’s work is autobiographical. Her art’s mode of autobiography works in favor of Poitras’s documentary.

Goldin is credited as being a producer of All the Beauty and the Bloodshed, and the film certainly benefits from access to her archives and voice. In general, giving a documentary’s subject too much control is deadening, because artists logically want to tell the most appealing, most heroic story about themselves, and what is most interesting is almost always the stuff that they don’t want to talk about: the equivocations, contradictions, compromises, and failures. This is also the problem with most gallery-produced biographical material, or most journalistic profiles of contemporary artists, for that matter. They tend to tell the same story: “here is an appealing figure with an exemplary life.” And that is boring.

Ultimately, All the Beauty and the Bloodshed remains exactly this: Not so far beneath the surface, it is a controlled story of why Goldin is an appealing and exemplary figure. But it nevertheless feels raw—and that’s because Goldin’s art itself is so raw. And so her artistic project fuses with the documentary project in a particular way, and what you get is up close with the artist but still feels like it hasn’t been sanitized of its jagged edges and question marks.

The major place where something like a more typically heroic story arc returns is in the contemporary P.A.I.N.-focused sections of the movie. The narrative of All the Beauty and the Bloodshed begins with a protest at the Met’s Sackler Wing, in front of the Temple of Dendur. At the end, we return there as Goldin and her allies rejoice to see the Sackler name removed. Two times when I have seen this film—once at the Firehouse Cinema in Manhattan and a separate time at a Q&A with the activists in the film that I moderated at the same venue—I have heard audience members say that they appreciate the movie as a story of a movement that won, in a time when nothing else seems to be winning.

Nan Goldin protests outside the United States Bankruptcy Court in White Plains to call out the United States justice system for allowing the billionaire Sackler Family to walk away unscathed after igniting one of the worst public health care scandals in the history of the nation. (Photo by Erik McGregor/LightRocket via Getty Images)

The Sackler story is not over, of course, and anti-Sackler protest goes on. The family is less acceptable in polite society; a settlement has been paid to states coping with the ongoing overdose crisis; and their company, Purdue Pharma, was dissolved—though not before, as the film notes, they maneuvered both to avoid liability and to remain one of the richest families in the U.S.

One of the most painful scenes in the film depicts something truly weird: a court-mandated two-hour video conference, where Sackler family members had to sit, their faces required to be on camera, and listen to the testimony of 26 people from 19 states who had lost families to addictions fueled by their business. But this episode is painful because you can feel as you watch it how symbolic it is, how little purchase shame has on great wealth.

I’m not a museum protest cynic. I think museum protests are important in a more than symbolic way. But as Rachel Hunter Himes wrote recently in n+1, they’re limited. And in some of the commentary and excitement about museum protest, I find that it gets caught up in a stock-heroic “artist-as-changemaker” narrative that plays more a role in marketing art than it does at measuring change. For their part, the activists of P.A.I.N. go on, trying to get the state to direct resources toward overdose prevention centers and other avenues to mitigate the harm done by the Sackler-fueled wave of painkiller addiction. That particular task will go on for years and years and years, without the cathartic narrative resolution of the museum funding protests.

Which is just to say that what shouldn’t be missed in All the Beauty and the Bloodshed is how equivocal the movie is about the victory over the Sackler name, not least because I think this unreconciled tone is informed by Goldin’s uncommon emotional honesty—the quality that makes her art feel so singular in the first place.

“Congress didn’t do anything,” Goldin says to the camera, speaking to Poitras’s camera at the Met after the “Sackler” name has come down. “The Justice Department didn’t do anything. Bankruptcy court completely left them better than ever—they’re completely vindicated by bankruptcy court. So this is the only place they are being held accountable—the only place. And we did it.”

Goldin breaks into a rare, cautious smile as she says those last words. It is all the more radiant for how rueful it is, for the frustration that the joy can’t dispel. It’s Poitras’s willingness to sit with that messy reality that I think makes All the Beauty and the Bloodshed special. It’s what, for me, gives this story about an artist the quality of art.