Back in June, when Tom Cotton published his instantly infamous “Send in the Troops” op-ed in the Times, he justified his call for using military force against Black Lives Matter protesters as the stance of a tough-minded realist speaking for the silent majority. “Some elites,” he wrote, “have excused this orgy of violence in the spirit of radical chic, calling it an understandable response to the wrongful death of George Floyd.”

That first link goes to a Fox News article about CNN’s Chris Cuomo saying that we should worry more about police violence than violent protesters.

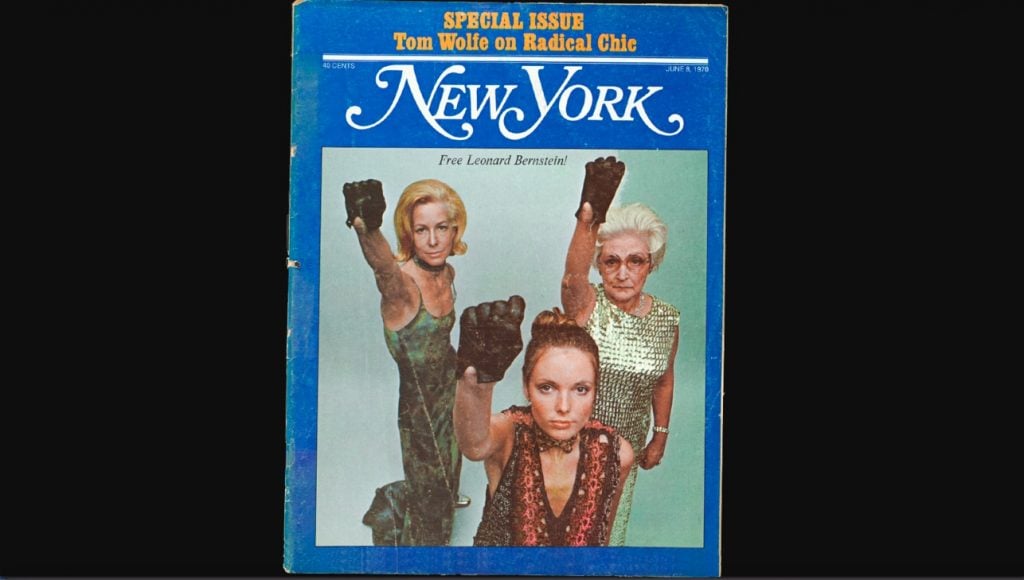

The second link pulls up Tom Wolfe’s 1970 New York magazine essay “Radical Chic: That Party at Lenny’s,” from whence the term “radical chic” entered the lexicon. It’s a remarkable achievement that an essay about an Upper East Side soirée from 50 years ago is still haunting the discourse.

The recent month of protest has been characterized by widespread debate about “performative activism” and “optical allyship.” You might hear the echoes of Wolfe’s criticism in these—or at least that’s how the New York Times’s Amanda Hess framed them a few years ago in an article called “Earning the ‘Woke’ Badge“: “In the ’70s, Americans who styled themselves as ‘radical chic’ communicated their social commitments by going to cocktail parties with Black Panthers. Now they photograph themselves reading the right books and tweet well-tuned platitudes in an effort to cultivate an image of themselves as politically engaged.”

A certain strain of liberal criticism can sound a bit like a certain strain of conservative criticism, eager to root out examples of elite social-justice gestures as out-of-touch, hollow spectacle. Recently, over at the New York Post, New Criterion editor Roger Kimball warned that media sympathy for the recent protests is merely the latest avatar of “radical chic,” little more than the privileged running interference for the criminal: “Now, in 2020, even more than in 1968, the left-liberal establishment is tripping over itself to embrace the radicals.” (Kimball also predicts, in passing, a BLM-inspired wave of terrorist bombings.)

I’ve used the term “radical chic” derisively in the past. The more I think about it now, the more I see the assumptions baked into the concept. Digging into its origins, in fact, helps provide a cautionary tale for the present. Maybe it even offers a compass to point the way through a tricky conversation.

Conservative Flak

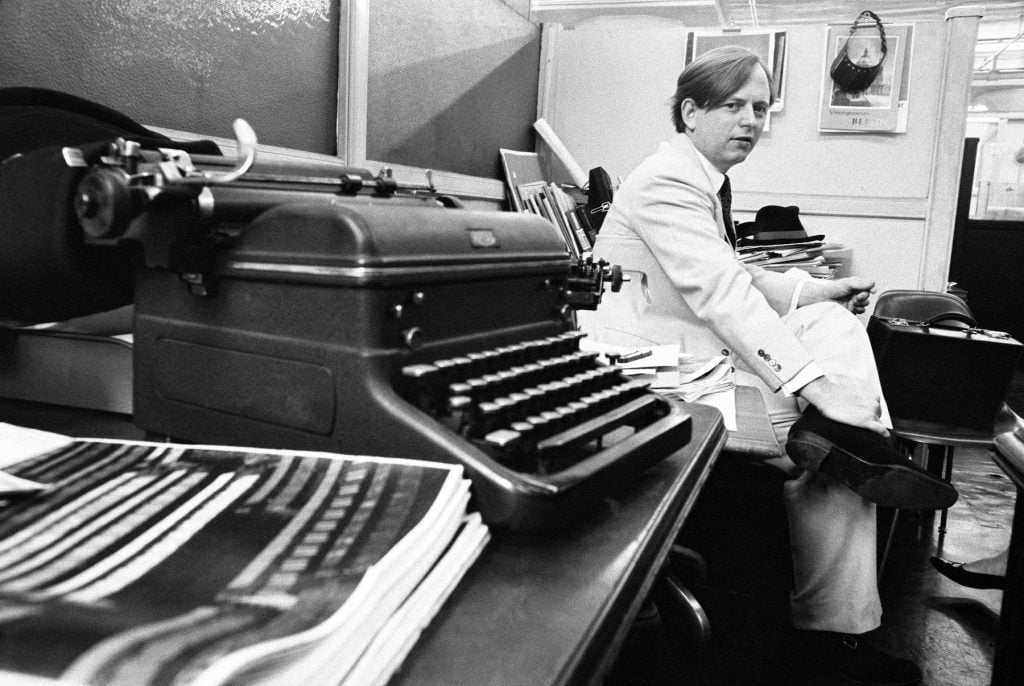

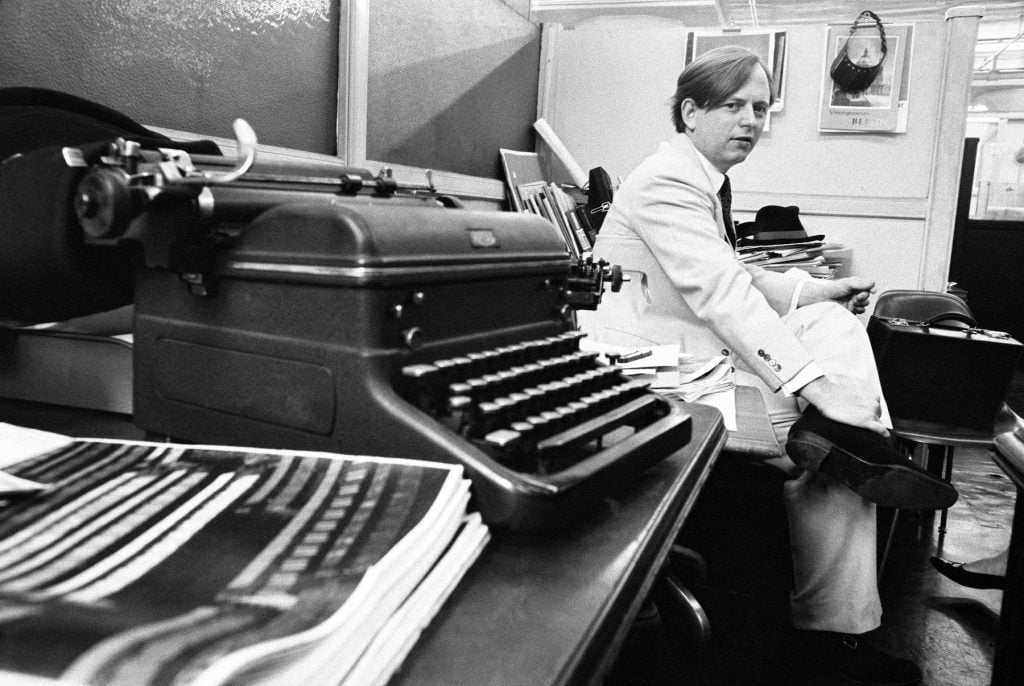

Portrait of American author and journalist Tom Wolfe, late 1965. Photo by Jack Robinson/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Cotton’s reference to the trope is tossed off, but it’s not random. “Radical chic” has come to mean all kinds of political poseur-ism, but its origin is very specifically about Black protest: Wolfe’s characteristically overwritten bit of social commentary concerns the sympathy for the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in cultural circles at the end of the 1960s.

Incidentally, I hadn’t remembered until I re-read “Radical Chic” just how key the art scene of the time was to the trope’s origin story. The essay’s central incident is a fundraiser at the Park Avenue penthouse duplex of maestro Leonard Bernstein (it was not actually thrown by him; his wife, Felicia, a long-time supporter of free speech causes, put it together). It focuses on Black Panther Party spokesman Don Cox’s attempts to win his tony audience over to supporting the cause of the Panther 21, a group charged with conspiracy to attack police and bomb the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens. They’d be acquitted of all charges a year later in what was then the longest and most expensive prosecution in New York history.

But a key character in “Radical Chic” is tuxedo-clad young art dealer Richard Feigen, who swings by the get-together on his way to a MoMA opening. Feigen’s interruption of Cox to demand info on how to throw his own Panther fundraiser is something like the central symbolic moment in Wolfe’s depiction of elite shallowness: “I won’t be able to stay for everything you have to say,” Feigen exclaims from the back of the room at one point, “but who do you call to give a party?”

As Wolfe puts it, “There you had a trend, a fashion, in its moment of naked triumph.”

While he is relatively restrained in his depiction of the Panthers, limiting himself to insinuating their anti-Semitism, Wolfe’s rhetorical innovation in “Radical Chic” was that by mocking the shallowness of the glitterati’s support of the Black Panther cause, you could essentially have license to belittle and trivialize Black activism by proxy.

If you doubt this is Wolfe’s basic purpose, read the essay that is paired with “Radical Chic” in its book form, “Mau-Mauing the Flak-Catchers.” That text is a deliberately grotesque, witheringly unsympathetic caricature of anti-poverty programs in San Francisco—what Wolfe calls “the poverty scene.” It portrayed them farcically as reducible to emasculated white bureaucrats being alternately duped and bullied by Black thugs.

Double-Edged Scorn

Leonard and Felicia Bernstein, 1967. Photo by Rudolf Dietrich/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

Nevertheless, it is “Radical Chic” that needled its way into the collective consciousness, partly because it packages contempt for leftist activism with celebrity gossip, two great American middlebrow pastimes.

Wolfe, as he himself admits, wasn’t the first to make a gag out of the Bernsteins’ Panther party. The event was ridiculed by tabloids around the world as soon as it first was reported in the New York Times society pages. The Times’s own editorial board quickly published a scathing broadside in response, decrying the “emergence of the Black Panthers as the romanticized darlings of the politico-cultural jet set.”

Essentially, the image of “That Party at Lenny’s” seems to have provided a tool that a mainstream universe of opinion, wearied by the disruptions of the 1960s, very much wanted to have at hand so they could begin dismissing all that upheaval as just a trend, like go-go boots or tie-dye.

It must be admitted, however, that Wolfe’s mockery would not be so durable or broadly effective if it did not strike at a weak point, channeling an archetype that the left itself had a shared investment in ridiculing: the image of the feckless bien-pensant who professes radical ideas that he doesn’t really believe. To get a sense of this reservoir of righteous irritation, go listen to folk singer Phil Ochs’s “Love Me, I’m a Liberal” from 1964, his satire of people who are “10 degrees to the left of center in good times, 10 degrees to the right of center when it affects them personally.”

And so, the term “radical chic” has lived a double life in the half century since. From one angle, in “Radical Chic and the Rise of a Therapeutics of Race,” Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn makes use of Wolfe’s account of the Bernstein affair as an example of the dead end of the 1960s focus on counterculture, how activism aimed at taking on the state and changing the law was deflected into aestheticized gestures of atonement, all under the hegemony of the liberal elite’s clueless guilty conscience.

But from another direction, in “Black Panthers, New Journalism, and the Rewriting of the Sixties,” Michael E. Staub focused on how Wolfe’s New Journalism (and that of other luminaries, including Joan Didion’s depiction of the Panthers as robotic child soldiers in The White Album), with its combination of creative writing and current-affairs reporting, was an effective instrument in reshaping the public profile of the Panthers for the until-then-somewhat-sympathetic liberal readership. By giving himself the license of inventing mortifying inner monologues, Wolfe recoded sympathies for Black radicals as embarrassing (e.g. when the Panther spokesman talks about the right to self-defense against violence, Wolfe inserts “and every woman in the room thinks of her husband … with his cocoa-butter jowls and Dior Men’s Boutique pajamas … ducking into the bathroom and locking the door and turning the shower on, so he can say later that he didn’t hear a thing…”)

The Radical Look

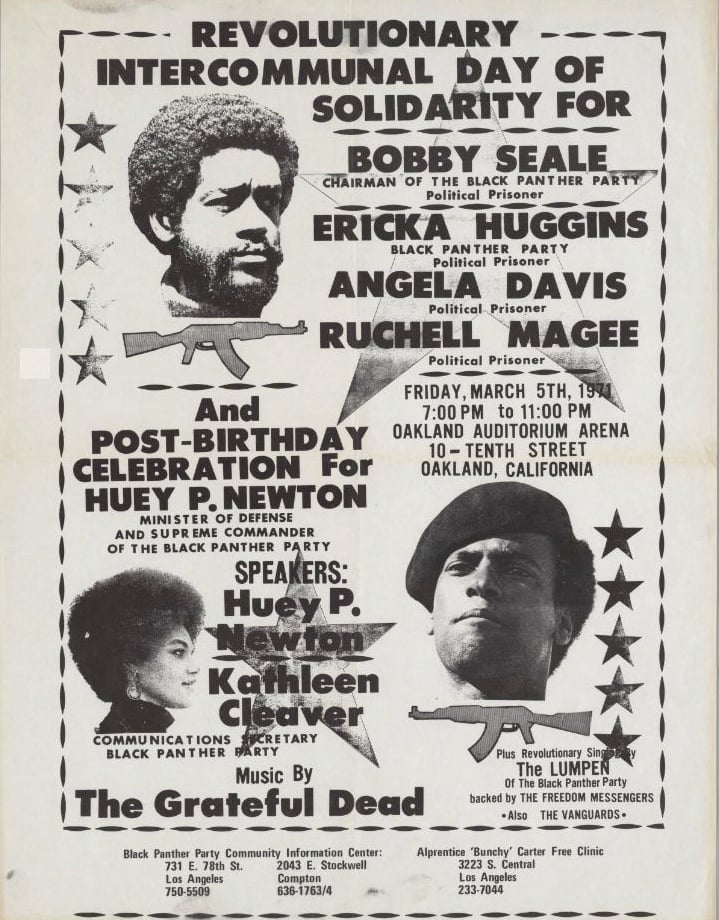

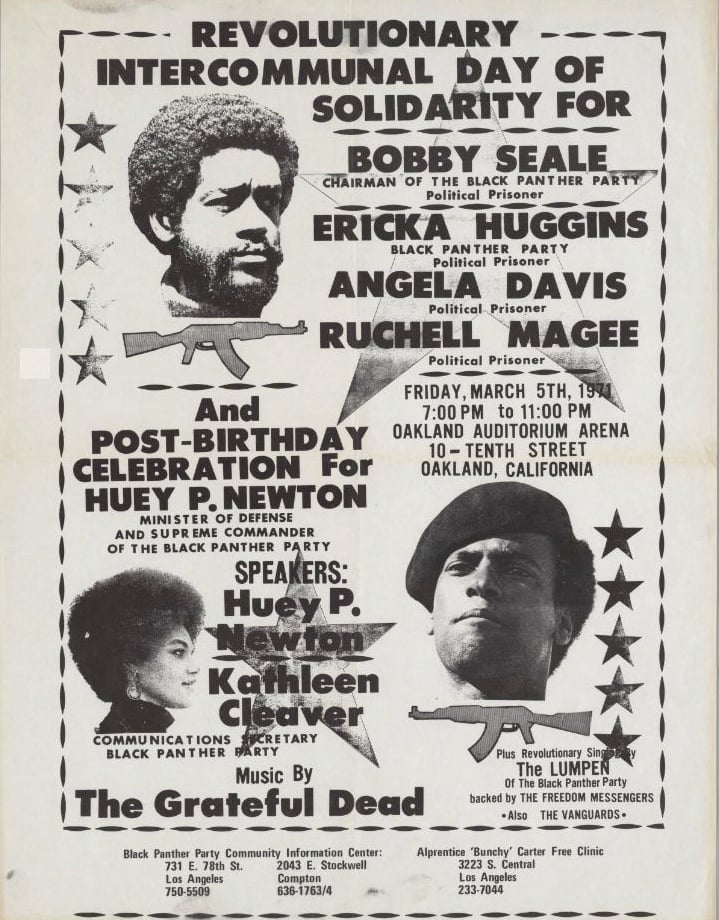

A Black Panther Party poster. Image courtesy of the Online Archive of California, UCLA Special Collections.

So, what lesson can be taken away from the affair for today, when the question of struggle for racial justice and culture’s awkward interface with it are both very public features of debate once again? I’d make three points.

The first is that one has to recognize that “radical chic,” when used as an epithet, is an implicit attempt to split two things apart—politics and style—that activists actually work hard to bring together.

We shouldn’t accept the premise that there is doughty “real” activism on one side and shallow spectacle on the other. Spectacle, performance, theatricality, etc. are very useful tools that activists employ to gain attention for a cause and win sympathies from wider layers of people. It is fundamentally a good thing for causes that you like to be cool and to command media attention.

The Panthers themselves were quite savvy on that front, as many scholars have argued. In his seminal 1987 cultural studies essay “Black Hair/Style Politics,” Kobena Mercer noted how Panther uniforms were consciously playing on preexisting lingo of rebel style, and this was part of what allowed them to make the splash they did: “The semiotic effectiveness of the Panther’s look derived from associations already ’embedded’ by previous articulations of the same or similar elements of style.”

More recently, Amy Abugo Ongiri’s book Spectacular Blackness advances the point even more forcefully, showing how the Panthers “successfully created allies out of the formerly uninitiated and apolitical through the wide-ranging appeal of an ideology scripted through an easily decipherable iconic language of images: the raised fist, the black jacket and beret, and the gun.”

Party Politics

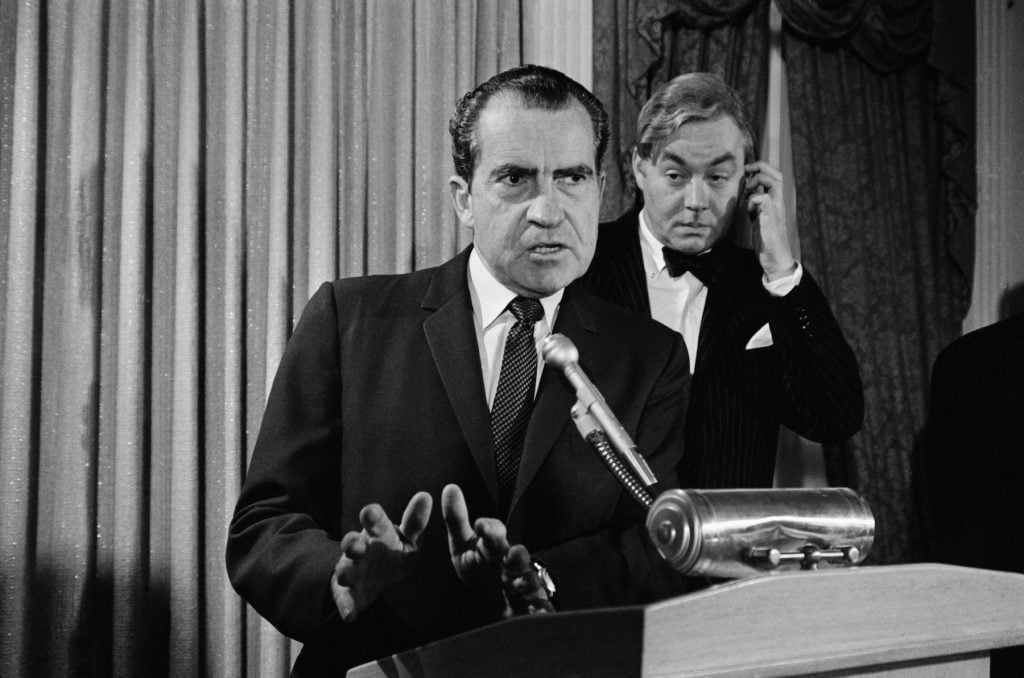

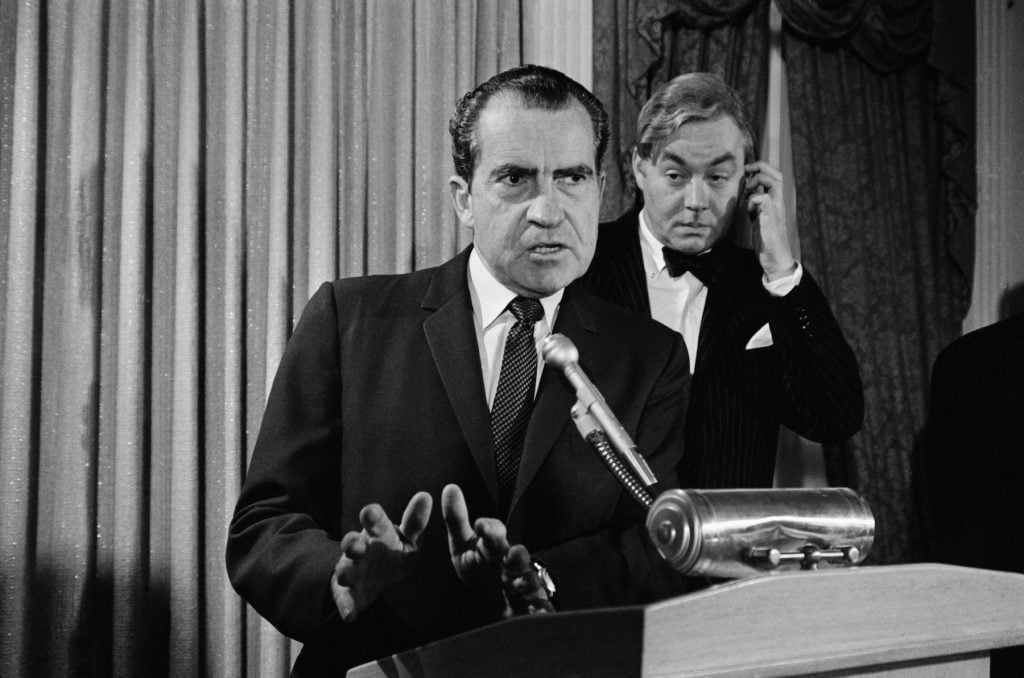

President elect Richard Nixon introduces the head of his council of urban affairs, Daniel P. Moynihan. Image courtesy Getty Images.

Well, fine. But it is one thing to court sympathetic media, and another for the cocktail-party set to mine radical causes for their personal amusement, isn’t it? Doesn’t that deserve full-tilt dismissal, à la Wolfe?

Immediately after the first report of the Bernstein party hit the society pages of the New York Times, presidential domestic-affairs advisor Daniel Moynihan penned his infamous “benign neglect” memo to Nixon on race relations. There, in a parenthetical, Moynahan makes the following comment explaining how the administration’s hard line against Black radicalism might be backfiring, referencing the police murder of Panther leader Fred Hampton:

The Panthers were apparently almost defunct until the Chicago police raided one of their headquarters and transformed them into culture heroes for the white—and black—middle class. You perhaps did not note on the society page of yesterday’s Times that Mrs. Leonard Bernstein gave a cocktail party on Wednesday to raise money for the Panthers. Mrs. W. Vincent Astor was among the guests. Mrs. Peter Duchin, “the rich blond [sic] wife of the orchestra leader” was thrilled. “I’ve never met a Panther,” she said. “This is a first for me.”

This cameo in the Moynihan memo is mentioned in Wolfe’s essay as being embarrassing to the Bernsteins, because it further amplified the scandal. But isn’t it proof that, however odd the Bernstein/Panther fundraiser seemed, it got the attention of the powerful? The event’s very incongruity was a signal, in the moment, that the Nixon administration had lost control of the narrative about an organization that it considered “the greatest threat to internal security of the country”—it suggested that sympathies for the Panthers were spreading in uncontrolled ways.

Conversely, when Wolfe’s acid-tinged New York piece came out months later, it was so effective at trivializing such support that Nixon’s assistant personally wrote Wolfe with praise: “I’ve seldom enjoyed a magazine article as much.”

Even in Wolfe’s own impishly reactionary account, he’s quite clear that the Radical Chic phenomenon had a charge of potential energy, ideologically. Describing the fallout of the negative press that greeted Bernstein fundraiser, he writes:

In general, the Radically Chic made a strategic withdrawal, denouncing the “witchhunt” of the press as they went. There was brief talk of a whole series of parties for the Panthers in and around New York, by way of showing the world that socialites and culturati were ready to stand up and be counted in defense of what the Panthers, and, for that matter, the Bernsteins, stood for. But it never happened. In fact, if the socialites already in line for Panther parties had gone ahead and given them in clear defiance of the opening round of attacks on the Panthers and the Bernsteins, they might well have struck an extraordinary counterblow in behalf of the Movement. This is, after all, a period of great confusion among culturati and liberal intellectuals generally, and one in which a decisive display of conviction and self-confidence can be overwhelming.

Of course, Wolfe’s essay was very clearly bringing the full force of his literary talent to bear on making any such persistence more difficult. (As Jamie Bernstein, daughter of Leonard and Felicia, reflected later, “his snide little piece of neo-journalism rendered him a veritable stooge for the FBI.”) Yet the fact remains that even the person who coined the term “Radical Chic” damned his targets, ultimately, not for fumbling towards solidarity but for being inconstant in that solidarity.

Another Take on “That Party”

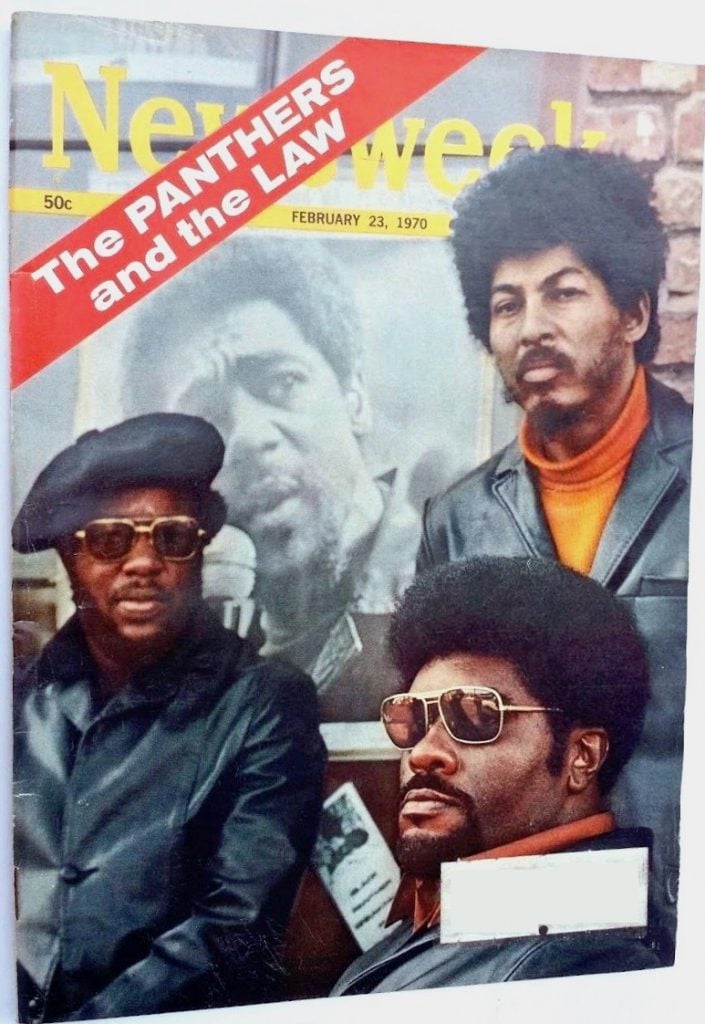

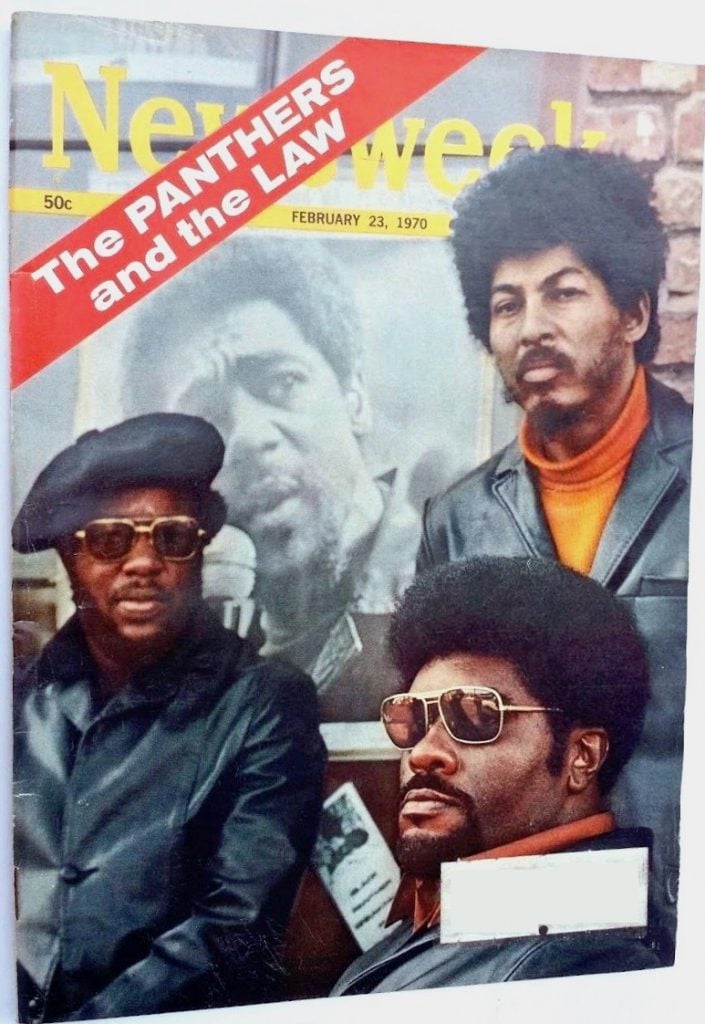

Don L. Cox (upper right) on the cover of Newsweek‘s February 23, 1970 issue.

But let’s not take Wolfe’s word for it. How does the story of “radical chic” look, told not from the imagined insides of the Bernsteins’ party guests’ heads, but from the POV of the political activists involved? Let’s look at the autobiography of Don Cox, the Panther spokesperson at the center of the account.

Cox lived an eventful life. His description of the Bernstein incident takes place between visiting Eldridge Cleaver in Algeria and debating politics against future congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton on the Dick Cavett Show. In all, the events of “Radical Chic” are given just a few paragraphs—a blip amid the larger backdrop of police persecution and the increasingly disturbing internal fights within the Party itself. By the time the Panthers became chic, they had been put in the pressure cooker.

Cox describes the Bernstein party as “a curious evening to say the least,” but he has positive things to say about the Bernsteins and also film director Otto Preminger, another subject of Wolfe’s filleting. He has less positive things to say about Barbara Walters and opera singer Leontyne Pryce. Here, however, are the key passages for me:

That night we managed to collect a decent sum to help toward bail money for the New York 21 but it was writer Tom Wolfe who profited most from the evening. He wrote a lengthy article about the affair for New York magazine and then later turned it into a book, Radical Chic & Mau-Mauing the Flak-Catchers, which received a wide readership. I wonder how much he made off all that. I never liked leeches and sneaks. He had snuck in with a tape recorder and recorded the whole evening so he could profit from the repression of the Panthers and mock our efforts to raise funds to free people who were subsequently found to be innocent, which we knew was the case all along. One who profits from the misery of others is a leech of the worst kind…

As this layer of American society began to give us support, the reaction from the authorities was immediate and fierce. They launched a national campaign of slander and intimidation against what they, following Tom Wolfe, called “radical chic.” Many of our supporters from that class were intimidated and retreated, and the rest of the evenings we had planned similar to the Bernstein affair were canceled. I had a secret meeting with Felicia Bernstein at the studio where she painted, and she told me of the misery she and Leonard had endured since the night of the gathering. They had been receiving constant hate mail and phone calls, including threats to their lives. She wanted to know if there was anything I could do to help. I could think of nothing, other than to reiterate my belief that all people should stand up and defend what they believe. Otherwise, fascism has fertile ground in which to grow.

The Lessons of Lenny’s

Demonstrators march in support of the Panther 21, New York, New York, April 4, 1970. Photo by David Fenton/Getty Images.

I find a useful moral here. The focusing of scorn on the incongruity of radical sentiments within an elite milieu has to be understood mainly as reflecting the status obsession and jockeying for position within that milieu. As the critic Morris Dickstein once wrote of Wolfe, the “snobbishness and triviality” of his characters “mirrors his own interests.”

If you center the story outside of the “scene” and instead on the needs of the organizers, such debates weren’t irrelevant—but from Cox’s point of view, they weren’t the main thing. Not really.

The main thing was, first of all, leveraging the available connections to get practical support to battle state repression. And, alongside that, there was a larger need that supporters shouldn’t be cowed by attempts to call into question their solidarities and sympathies—because that was part of what makes backlash possible, isolating movements, empowering foes. They should stick it out, Cox thought. They should deepen their commitments.

“Radical chic,” as a ready-to-hand framing of such matters, proved an effective rhetorical instrument to undermine both those objectives, with consequences both short- and long-term.

Today we don’t live in the same symbolic universe as 1970. Few things hold the center of attention the way Wolfe’s essay did. Political symbols are circulated into new, disjointed social spaces, mined for their energy, and turned into fashion infinitely faster—with a correspondingly much greater and more intense public emphasis on questioning the authenticity and conviction and motives of the people sharing them.

Such debates are important, since there is a continuous effort to appropriate the symbolic energy of protest for ends at odds with its original intentions. But if the classic instance of “radical chic” is any guide, whatever awkward conversations its latter-day incarnations produce are better, much better, than the alternative: symbolic isolation for causes one believes in, which can have real effects. There are after all people in the wings waiting to call in the troops.