Opinion

How I Found Sigmar Polke Alive and Well in a German Spa Town

In his latest column, Kenny Schachter reflects on a recent encounter with his longtime artistic idol.

In his latest column, Kenny Schachter reflects on a recent encounter with his longtime artistic idol.

Kenny Schachter

The Museum Frieder Burda was opened by the eponymous publisher in 2004 in a Richard Meier building in the German spa town of Baden-Baden (literally “Bath-Bath”) known for its natural springs and one of Europe’s very first casinos, dating to 1765 and in full swing, still. I dropped by to visit the Sigmar Polke exhibition entitled “Alchemy and Arabesque,” but sadly didn’t stay quite long enough to pop into a hot spring—though I did manage a side trip to the lavish Rococo casino, admired by as diverse a clientele as Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Marlene Dietrich…and Andreas Gursky. The title of the Polke show is a little unfortunate; though the alchemy is ostensible, the arabesque is more like a kitchen-sink approach to capturing past, present, and future reflections/impressions in a boiling cauldron: Polke’s perfervid imagination.

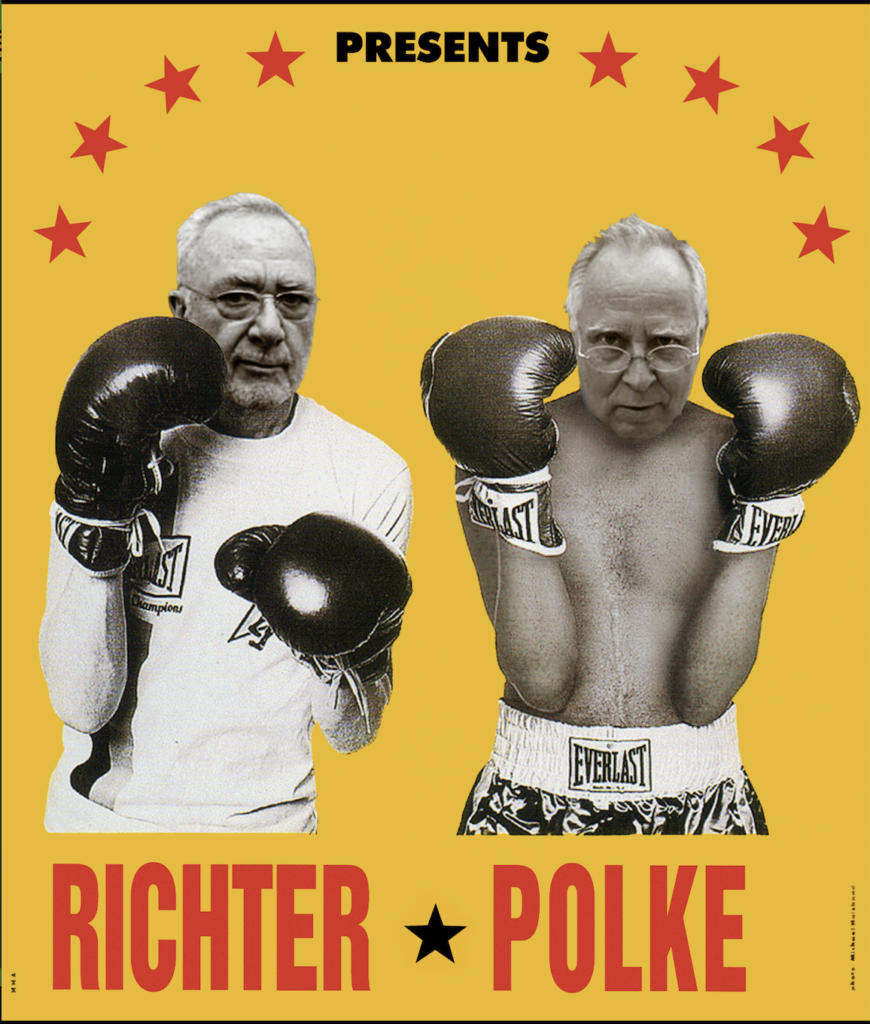

Polke and Gerhard Richter represent for me two pinnacles of postwar German art, akin to the relationship and position of Robert Rauschenberg—the subject of a not-to-be missed Tate Modern show through April 2—and Jasper Johns in the U.S. Polke and Rauschenberg were sloppy and experimental (and are now dead) while their living counterparts, Richter and Johns, are more controlled and (seemingly) erudite. I’ve long been involved with Polke and Richter since the first exhibit I curated, “German Paper” at Sandra Gering Gallery in New York in 1990, which covered a wide range of drawings and works on paper. Most recently, I organized “polke/richter richter/polke” in 2014 in the private treaty gallery of Christie’s London. Commercial galleries were reticent to get involved for fear of alienating Richter, but the heavyweight artist embraced the show and sanctioned every page of the catalogue translation.

A promotional image from the Christie’s show. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

I had taken for granted that Polke and Richter regularly exhibited alongside one another, but, until the 2014 show, they hadn’t since the 1966 “polke/richter” at galerie h in Hannover, nearly 50 years before. A collaborative essay that the artists composed for that earlier show was only translated on the occasion of the Christie’s book; other than that, I could find only a single interview with Polke dating back to 1984, with Bice Curiger, reprinted in a 1990 issue of Parkett. Polke was taciturn to the extreme, repeatedly truant when journalists came calling, even when they were armed with appointments. The galerie h essay was an abstract mashup of uncredited texts by both artists mixed with random passages from popular pulp science fiction; ferreting out which snippets were by which artist was fun and frustrating, but helped in the Christie’s book by crib notes supplied by Dietmar Elger, head of Richter’s (exhaustively exhaustive) archives.

Polke, who was hand-painting Ben-Day dots from newspaper imagery at the time (and throughout his career—among his few steadies), capturing his missteps while re-presenting cropped press pictures, stated in the 1966 catalogue: “Believe it or not, I see the world in dots. I love all dots. I am married to many dots. I support happiness for dots. The dots are my brothers. (I am a dot as well.)” This farcical nonsense captures Polke’s eccentricity and wackiness, but was offset by his later comment to Curiger: “Agony is lurking behind every hair, every color, every picture.” You get the feeling that even when tragedy struck (as it did indeed with Polke’s unfortunate, premature passing) the funny was an important resource and remedy—as much as defense.

Back in Baden-Baden, the Museum Frieder Burda show is a beautiful, discrete exhibition that dips into many different strands of Polke’s work—photography, painting, drawing, conceptual pieces incorporating masking tape (and rubber bands), and artifacts from his personal collection—modestly, with grace and cohesion. Curated by Helmut Friedel, the show tells the story of a restless, not-easily-pegged-down wanderer who enjoyed experimenting with materials perhaps best avoided by anyone other than hazmat-clad military personnel. There is an extension of the show in the museum’s Berlin satellite space. They have an awful lot of Polkes.

An installation view of the Sigmar Polke show at Museum Frieder Burda. Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Like a naughty child harboring contraband, Polke delighted in danger; if the toxicity of his chosen means of expression didn’t kill him, it undoubtedly hastened the process—and I’m not sure he’d have been too bothered by it. Impregnating photosensitive negatives with uranium augmented by a glass collection infused with the same radioactive substance, also on view at the Burda, is not exactly a recipe for clean-living longevity. In thus exposing himself (including too a potpourri of other contaminants), Polke played with the seeds of his own demise. In his words, again to Curiger: “Poison has consequences. Art has none. Except maybe a slow acting one…. Poison just crept into my pictures. I was looking for brilliance of color, and it happened to be toxic…. In small doses it can be medicinal.” But Polke didn’t do diminutive—he had a voracious, ambitiously scaled output.

Many of the paintings have a sketch-like quality that bring to mind Claude Monet simultaneously working on multiple canvases in his Giverny garden; those works, ultimately stamped by the Monet estate, were never intended as discrete, finished artworks. Painting for Polke was similarly a continuum—he wasn’t interested in making art product, but rather was manically engaged in an unquenchable quest. He was a mad uncle, a merry prankster in the mold of Ken Kesey.

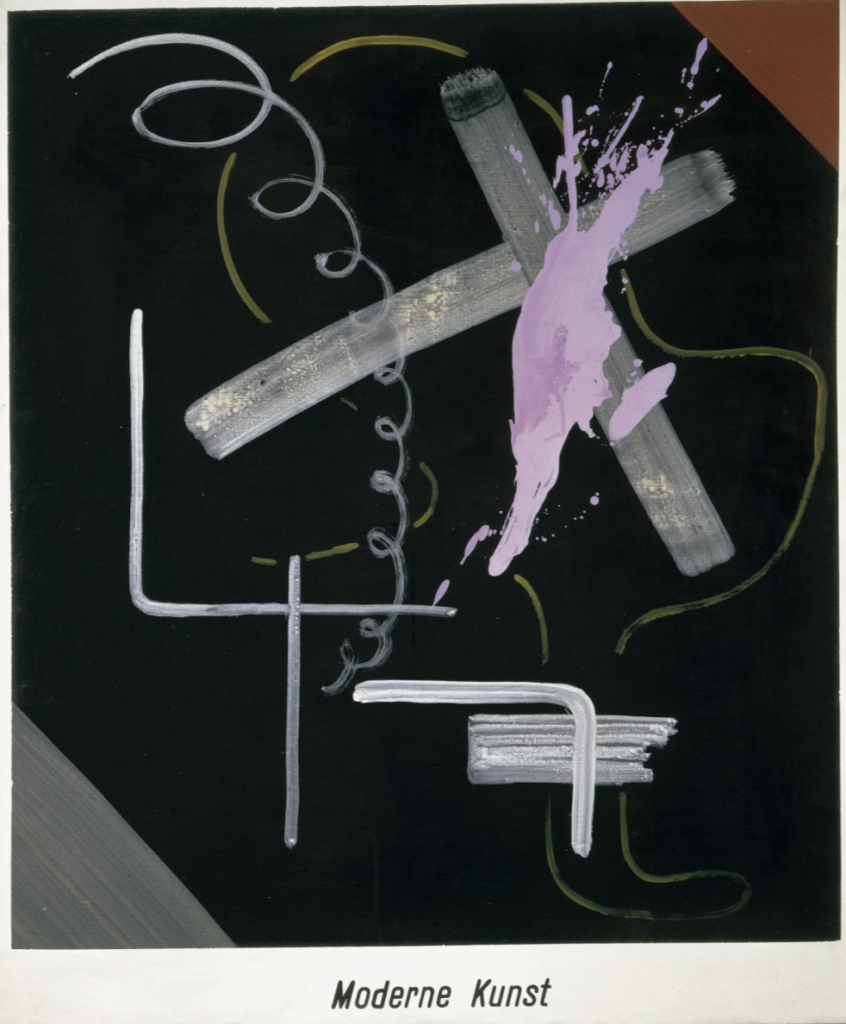

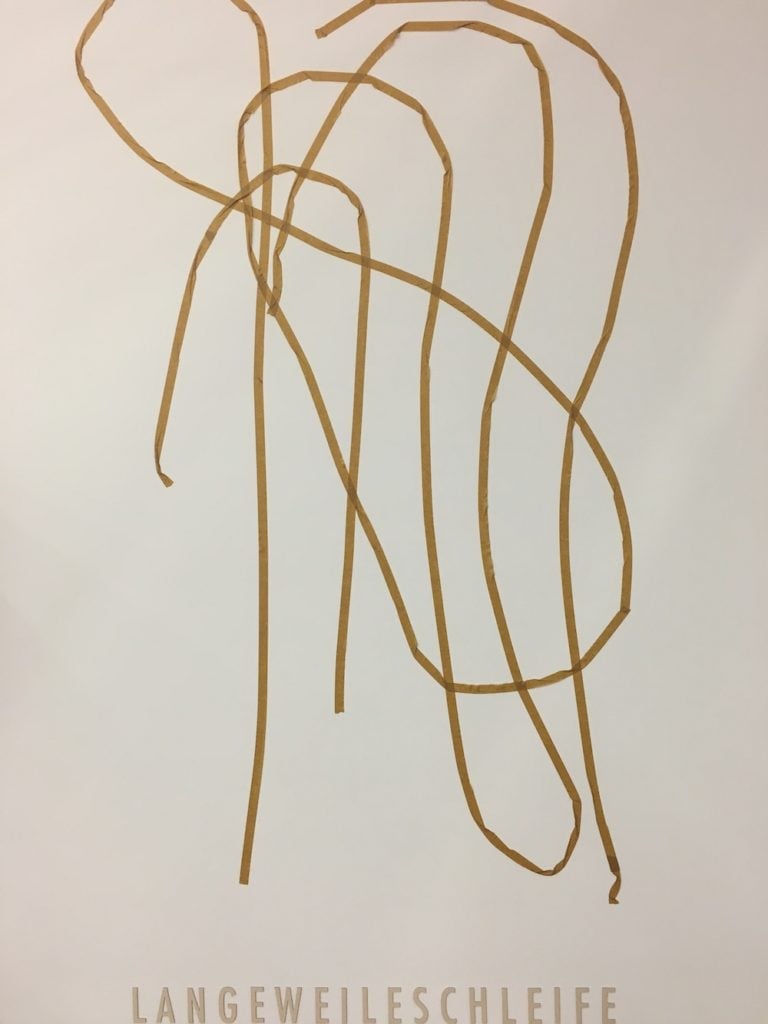

On view at the Burda, the 1968 painting Modern Art attacks the iconic status afforded reductive, abstract gestures by staining such a canvas with a splotch mockingly splashed across the surface. The Higher Powers Command: Paint the Upper Right Corner Black! from 1969, jabs at the notion of the isolated genius getting inspiration from above. Annoyingly, as Polke was known to install paintings from the ceiling (and, once, on the outside of a building!), curators take license to hang works unorthodoxly high. The 1969 work Boredom, consisting of nothing more than an oversized doodle comprised of throwaway tape affixed to the wall, was a sendoff of the sanctity of the very impetus to create. A 1960s Polke came with wry humor and biting sarcasm as standard.

Sigmar Polke, Modern Art (1968 Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

In later paintings, Polke applied globs of paint and sundry other materials, layered with his inimitable curlicues and appropriations, as distinct as the lines of Picasso. As much as the early works served up a hefty dose critical commentary, the later paintings were an architecturally sized fuck you to pictorial convention; giant, pared-down clouds of color vibrating in light, oftentimes sagging from the sheer weight of resin and pigment coupled with bad stretching and a dose of entropy. Polke’s chemical wisps float through space, traces of what look like random, arbitrary drips and spills. Neoclassical shards, fragments, and non-sequiturs in the way of hidden faces, demons, and ghosts swathed in hanging stains play a constant game of hide-and-seek.

To compare markets, Gerhard Richter, at 85 years of age this month (on February 9), has 16 more years (and counting) of prodigious production with no signs of slowing; Polke was 69 at the time of his death, June 10, 2010. To date, Richter has sold 5,527 pieces at auction to Polke’s 3,004. Part of the disparity in painting prices resides in the fact that Richter’s catalogues raisonnés have catalogues raisonnés, while Polke famously has none (yet); if he had wanted one, we’d be lucky enough to have it now. Twenty-one Richter paintings have fetched above $20 million (his top price is $46,352,960), while Polke has only one in that category—and after his $27 million record, Polke prices precipitously drop to $9 million. Yes, a Richter will always be more uniformly palatable and valuable, but—as gross and ludicrous as this may currently appear—a $27 million Polke will soon be considered a bargain. By the way, Johns’s auction record is $36 million and Rauschenberg’s $18 million, a very similar ratio to Richter vs. Polke.

At the post-opening dinner, I was the only English-speaking guest, but I could hear again and again: “Polke,” “Richter,” “Richter,” “Polke.” Some things never change. I liked being the solitary foreigner, which at the same time made me feel more connected to my environs, by art (gratefully bucking “Great America” syndrome). Similarly, Polke was unto himself as a practicing artist. Afterwards, a group ended up at the casino where Gursky, famous for depicting raves in his big-screen-sized photos, staged one of his very own after his show at the Burda in 2015. Among us was the effervescent, irreverent daughter of Polke, who I wanted to be near so as to glimpse his wondrous presence. The family spirit was infectious: father/daughter untethered by the mundane.

Sigmar Polke, Boredom (1969). Courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Polke fought fame and fortune, an impenetrable recluse who wasn’t just gleefully making paintings (although that too) but destabilizing the entire medium and history, tearing through its pages to cut-and-paste a new art form. Gallerist Marc Glimcher recounted a Polke studio visit his father arranged when he was a(n errant) teen and told of a rip-roaring, giggling artist dancing around his studio to a tune of his own devising that only he could hear. Polke’s public will expand exponentially, just watch. Polke the clown, an intoxicating (intoxicated) discoverer—he built and destroyed worlds on the same canvases, photographs, and paper works.

“We don’t need pictures, we don’t need painters, we don’t need artists,” he said. “We don’t need any of that. What do you get out of an artist?” A self-negating nihilist, Polke nevertheless never quit. “Art is cannibalism,” he noted, and it actually, physically did him in. The art business, which Polke assiduously shied away from, has a tendency to eat away at your innards too. In the end, Polke had no kryptonite to shield him from the well-known, deadly effects of his chosen poisons. It saddens me to think of what might he might have done for another 10 to 20 with such gifts and proclivities. Polke wasn’t a dot, inasmuch as we are all specs in the scheme of things. He was significantly more—a scientist, magician, and great artist who strove to fail as much as succeed. Jesus may have died for our sins, but Polke perished for our pleasures (and enlightenment).