Opinion

Why the Art World Shouldn’t Be Congratulating Itself on Donald Trump’s Defeat

Did the last four years of politicized culture break art's bubble or strengthen it?

Did the last four years of politicized culture break art's bubble or strengthen it?

Ben Davis

Turn your mind back to 2016 and Donald Trump’s shock election.

He had been treated as a joke and a freak, with little serious chance of winning. Everything that came after, culturally speaking, has to be understood in the context. The extreme shock of the moment came not just from the fact that he was seen as vile and vulgar, but the fact that liberal opinion had convinced itself that a President Trump surely shouldn’t and couldn’t happen.

Then came election night. Pundits had been predicting not just a victory but a Republican wipeout and permanent chastisement. Instead, the GOP retained its hold on the Congress, giving the Party of Trump the ability to make law.

The lesson of 2016 was certainly not about the power or perspicacity of liberal media culture. Celebrities and pop stars and artists had all been pretty anti-Trump, explicitly or implicitly. Their sentiments had evidently failed to motivate the key constituencies.

But all that frustrated, frantic liberal energy had to go someplace. So a lot of the Resistance energy went into symbolism, culture, media commentary, into taking whatever the implicit liberal perspective had been and making it more outspoken, more denunciatory, more confrontational.

“Against normalization” was the rallying cry of the early Trump era. In truth, I don’t think Trump was ever really in danger of being “normalized”: Donald Trump calls attention to his own exceptional outrageousness any chance he gets. His entire appeal to begin with was that he was not, in terms of cultural mores at least, a normal Republican.

Throughout his excruciating tenure, Trump has been the master signifier dominating conversation at all levels of US society, in a historically unique way. The fact that every bit of trivial pop culture was swept up in a running commentary on Trump was already a joke early on.

Joining battle at the level of the discourse, the commentariat went through a near-continuous ritual of getting excited and hyping the importance of some cultural figure who had called out the Trump regime: the cast of Hamilton or Meryl Streep or Michelle Wolf. This happened even though, it bears repeating, the lesson of Trump’s first election was that figures like the cast of Hamilton or Meryl Streep or Michelle Wolf were not nearly as politically consequential as had been thought.

An Ivanka Trump look-alike model vacuums bread crumbs thrown by visitors as part of Jennifer Rubell’s art installation titled “Ivanka Vacuuming” at the Flashpoint Gallery on February 07, 2019 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

The ensuing mainstream cultural texture, from Stephen Colbert’s Christmas cartoon imagining Robert Mueller teaming up with Santa Claus against Trump to artist Jennifer Rubell’s odd, viral Ivanka Vacuuming performance, tended to blur together into anti-Trump symbolic theater. It was culture framed as if it were speaking truth to power. But really it was about making the pre-existing liberal audience for media and culture feel that it was still powerful, still tossing crumbs at Ivanka instead of the other way around.

In a recent piece on how Trump killed political comedy, one of the writers for Trevor Noah’s leaden version of the Daily Show admits that its liberal audience has become intolerant of ambiguity in the Age of Trump: “You almost have to not couch things in sarcasm, because people will momentarily wonder if you’re not on their side.”

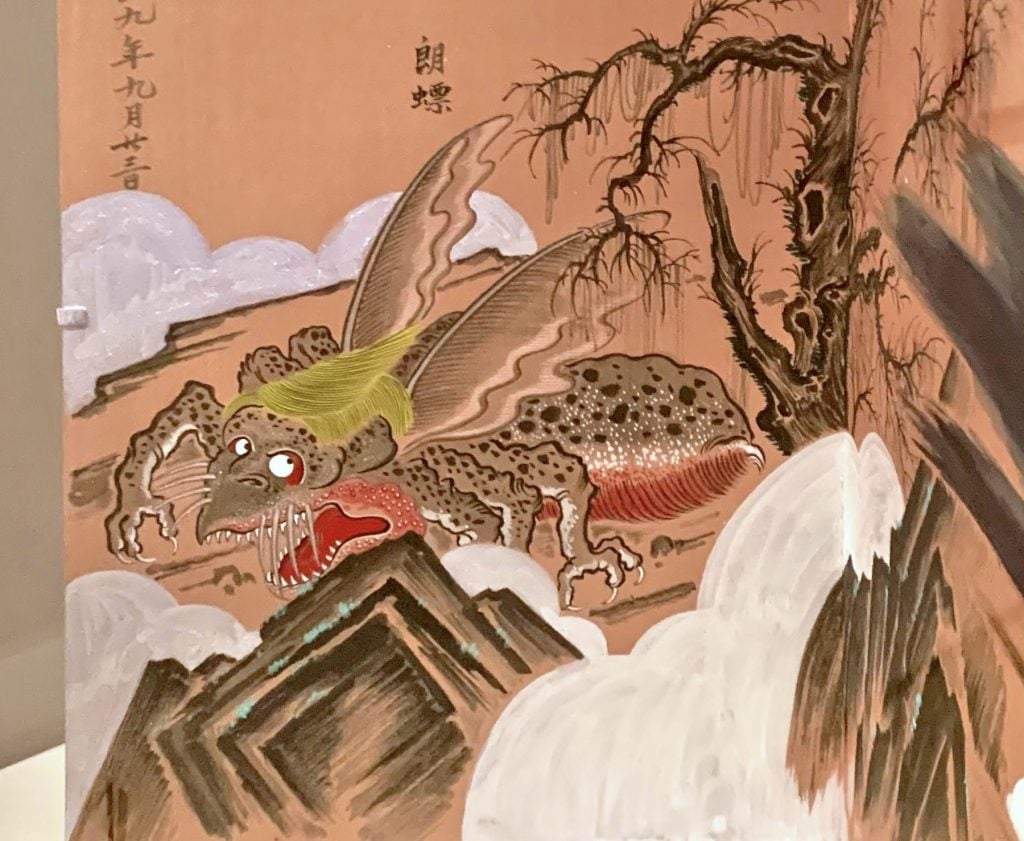

The products of this bottomless anti-Trump cultural hunger, organized around quick hits of ownage, are going to age like Taco Bell leftovers. At the just-opened Asia Society Triennial, the artist Sun Xun has a piece, commissioned specially for the event, that is a Chinese-style scroll painting starring an evil dragon who has Trump features, paired with lines from the Declaration of Independence about the abuses of King George.

Sun Xun, July Coming Soon (2019) in the Asia Society Triennial. (Image by Ben Davis.)

Even with Trump still hogging headlines, this kind of work already looks extremely dated and goofy.

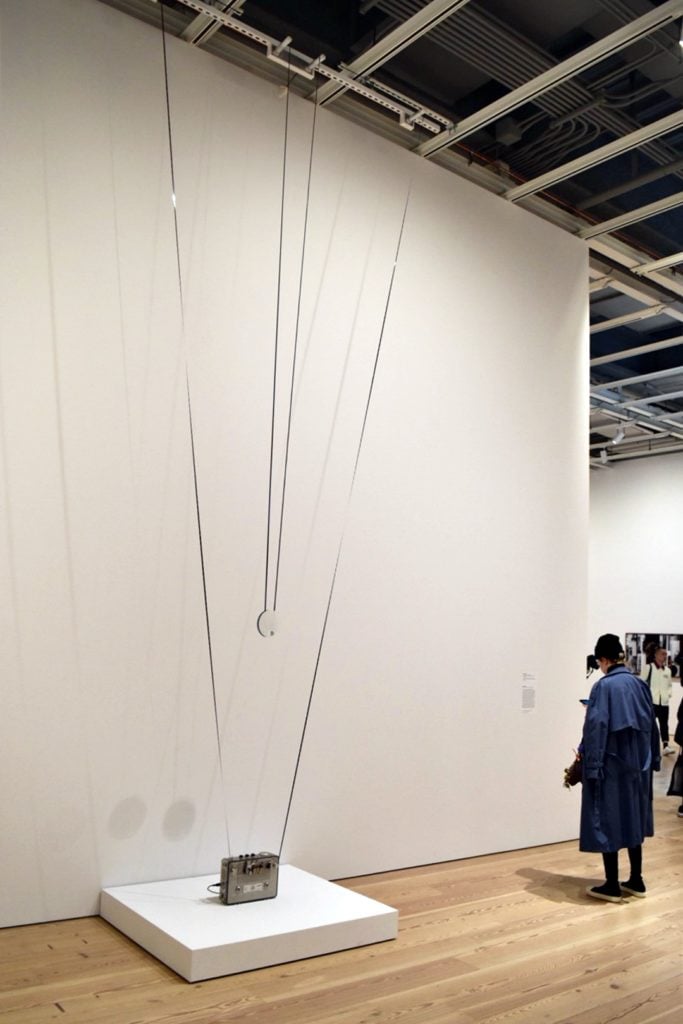

When I think of the art industry’s reaction to Trump, I think of Marcus Fischer’s Untitled (Words of Concern). Recorded in 2017 and shown at the 2019 Whitney Biennial, it was an audio work presented in the museum as a tape recorder, playing snippets of the voices of artists at the Rauschenberg Residencies that Fischer had recorded just before Donald Trump 2017 inauguration. He had asked them to name the issues they worried about in the wake of the shock event.

Marcus Fischer, Untitled (Words of Concern) (2017). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

On the tape, you heard a diverse variety of voices come, one after another: “Guns… private prisons… fear as a constant state… polar bears… poverty… private armies… fascism… Russia… the oil industry… the loss of good relations with other countries….”

It had the air of a kind of ASMR for the Resistance. As a list of concerns, it was not particularly revelatory—NPR in audio collage form. In terms of challenging its assumed audience or finding a language to reach beyond it, its value was nil.

What the artwork did successfully accomplish, however, was to mark the galleries as being a place where a certain kind of community, with a certain set of values, could feel itself seen. Specifically, the kind of community capable of seeing its own reflection in the inhabitants of an elite island artist residency.

And, you know, I am one of those people. I think that “fascism” is a slightly misleading way to understand Trumpism, and the obsession with “Russia” was a huge political waste of time that allowed Democrats to avoid owning their own failures to offer any message besides “I’m not Trump.” But I generally share the overall concerns listed above, and I am glad art is a place where they are taken seriously (at least rhetorically).

But the arts exist as a smaller bubble within the larger bubble of liberal media culture. And doubling down on affirming the sense of enlightened cultural superiority has larger potential negative consequences.

The first of these is that culture assured of its own righteousness and obsessed with the singular figure of Trump inherently tends to cartoon the quote-unquote “other side.” Maybe I’ve missed all the artworks that help explain the various dimensions of the 72 million-strong Trump coalition, but my sense is that people still paint with a pretty broad brush.

Clearly, Trump is a singularly off-putting, chaotic, alarming figure, and there is something to emphasizing that fact. Biden won a record vote total without much in the way of strong message besides “wear a mask” and “remember Obama?”, in an election that was essentially a referendum on the sitting president.

But, then, a record number of people also voted for Trump—more than last time, and more than Obama’s previously record-smashing 2008 total.

And, as it so happened, the decisive difference was not at all what people in my world thought it would be. Trump lost ground in his base of white men—both college-educated and non-college-educated. And meanwhile (the data is still coming in, but pre-election surveys indicated it as well) he seems to have picked up ground with minorities. And despite predictions of a “seismic shift” in their votes, “white women seem to have maintained or slightly increased their level of support for Trump compared to 2016,” according to NBC.

To be clear: the shift is not enough to say that Trumpism is not, still, a white man’s movement—but since the entire cultural discourse for four years framed the 2020 election as a referendum on misogyny and white supremacy, this has to be an at least mildly surprising result. Enough to make you ask if the ambient liberal cultural consensus either misstated the case, or stated it in a way that actually put people off.

That brings me to the second negative consequence of the Trump-era liberal strategy of compensatory cultural warfare. There is good reason to think that part of Trump’s appeal—I stress, a part—is exactly that he enrages the cultural sensibilities of college-educated liberals.

In a great article from the New York Times Magazine, Elaina Plott talks about how Trump’s base is actually much more ideologically plastic than people think (“more polarized but less ideological,” as one strategist puts it). What seems to unite vast swaths is a deep connection to his combative, insult-comic style. A very, very large number of people don’t see themselves represented in “official” discourse, view its norms as judgmental and smug in ways that are invisible to those immersed in it, and love to see Donald Trump make people on TV blow steam out of their ears.

Only a little more than a third of the adult population has a college degree. People with college degrees occupy all the plum media, culture, and political jobs. Education level is the best predictor of museum or gallery attendance. It is also inversely correlated to Trump support. Art is, therefore, uniquely badly placed to diagnose accurately the problem at hand or address it.

In Vox, four years ago—before Trump—Emmett Rensin already referred to the warping effects of what he called the “Smug Style in American Liberalism,” which he linked to official liberalism’s turn towards finance and white-collar professionals and away from blue-collar laborers: “a politics defined by a command of the Correct Facts and signaled by an allegiance to the Correct Culture.” (Among the professions most associated with Democrats, according to a Bloomberg analysis of small donations, are “professors,” “deans,” and “editors”—the cultural supervisor class, essentially.)

A study by Lucian Gideon Conway III et al, executed after the 2016 election, found that people exposed to “overzealous policing of communication norms” could help predict increased support of Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton. Associating liberal ideals with “correct” forms of speech and cultural expression caused people to reject liberal causes as judgmental and condescending. The authors stressed, “this backfiring doesn’t just occur for norms that are genuinely repressive to political freedom—it also occurs for norms that have a clearly good and noble aim.”

In the final days before the election, the Times had a piece on the political battle in a small Wisconsin town in Oneida County. The town’s most enthusiastic Biden booster was Kirk Bangstad, a human cartoon of what conservatives think liberals are: the Harvard-educated former policy director for Anthony Weiner, a Silicon Valley “tech strategist” and one-time aspiring opera singer, who had moved into the conservative county to take over a riverfront brewpub.

Bangstad had taken it upon himself to be the “town shamer” about mask wearing, starting a Facebook page to call out people who didn’t comply. “A lot of them, I feel, haven’t been equipped with the tools of media literacy or critical thinking skills to be able to discern if they’re being told something that doesn’t quite jell or is not true,” Bangstad said of the neighbors he was trying to win over. “What’s wrong with being elitist? Why are we so anti-intellectual right now? Why is having is having a beer with something more of a political asset than potentially believing that they are a cocky asshole but believing that they can make your life better?”

Even if you passionately believe in the power of masks (as you should!) and agree with Bangstad’s assessment, embracing the political identity of “cocky asshole,” shaming people, and treating them as dumb rubes is a sure way to get them not to listen to whatever valid points you might have. If these are the kinds of political communication skills that the Harvard/Silicon Valley/opera lover/Democrat policy wonk culture is incubating, it is a long-term loser.

(In the wake of Biden’s election, Bangstad triumphantly unveiled a “Biden Beer.” He advertised it as “inoffensive and not too bitter.”)

It appears this liberal affect is a short-term loser as well: despite Trump’s historic unpopularity and the record turnout it inspired, the Democrats pulled off the amazing trick of simultaneously losing House seats, failing (for now) a takeover of the Senate, and above all utterly botching the chance to turn state legislatures, guaranteeing a fresh decade of Republican dominance of state policy in the United States.

Art’s impulse in such times is to ask “how can art help the nation heal?” But that question itself starts from the false premise that “art” is some kind of universal instrument, and not a set of symbolic practices embedded in a very specific cosmopolitan subculture. If the institutions of art and culture more generally have played even a small role in flattering an insularity that makes it harder and harder to see that, and thus to speak to broader layers of people, then they have done harm to the very causes that they want to champion.

Before we ask whether art can heal, we need to recall the Hippocratic oath: first do no harm.