Op-Ed

There Is a Long History of Vandalizing Art for a Cause. But Is It Effective?

The author of "Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age" explores what the past can teach us about the current eco-protest wave.

The author of "Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age" explores what the past can teach us about the current eco-protest wave.

Farah Nayeri

Tomato soup. Mashed potatoes. Glue and red glop. Whatever next?

Climate activists eager for global attention have found a new platform on which to vent their rage: masterpiece paintings by Botticelli, Constable, Van Gogh, Monet, and Vermeer.

Wearing t-shirts emblazoned with anti-oil slogans, they have flung canned tomato soup at Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, smeared mashed potatoes over Monet’s Haystacks, and glued themselves to Vermeer’s Girl With a Pearl Earring while a thick red goo was poured over them.

The Musée d’Orsay in Paris nearly became the scene of another eco-attack last week, when a climate activist tried and failed to throw soup at paintings by Van Gogh and Gauguin. By the time this piece is published, still more attacks may have taken place.

The aim of the activists is to get the message out loud and clear: unless industrialized nations act quickly and radically to cut carbon emissions and stop all new oil and gas projects, the world will fall to pieces. “We are in a climate catastrophe, and all you are afraid of is tomato soup or mashed potatoes on a painting,” yelled a German activist after daubing Monet with puree. “When will you finally start to listen?”

Vandalism of art is nothing new, as I write in my book Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age, released earlier this year. The book shows how Western art is becoming more and more democratic, inclusive, and accessible—and more and more exposed to attack.

Farah Nayeri, Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age (2022).

Before the birth of public museums in Europe in the 18th century, great art was out of the general public’s reach. Today, it is completely accessible. Seeing a great painting has become as easy as reading a book, listening to music, or streaming a TV series. In Britain, national museums are free; you can walk right in and see their permanent collections. Elsewhere in Europe and in the U.S., admission costs roughly as much as a movie ticket.

Unlike books, music, and movies, however, paintings cannot be replicated and released in large multiples. No copy, photograph, video, or virtual-reality experience can ever come close to conveying the wonder of seeing the real thing.

That uniqueness has not prevented paintings from becoming intermittent targets of public bile. Attacks against them have even escalated with the rise of 24-hour news and social media. As I write in my book, a new kind of vandal has emerged: the vandal with a cause.

An early example is the militant suffragette who attacked Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus at the National Gallery in London in March 1914. To protest the arrest of a fellow suffragette, Mary Richardson hacked away at the masterpiece with a meat cleaver. By the time she was done, there were half a dozen gashes on the surface of the painting (which were, mercifully, later repaired).

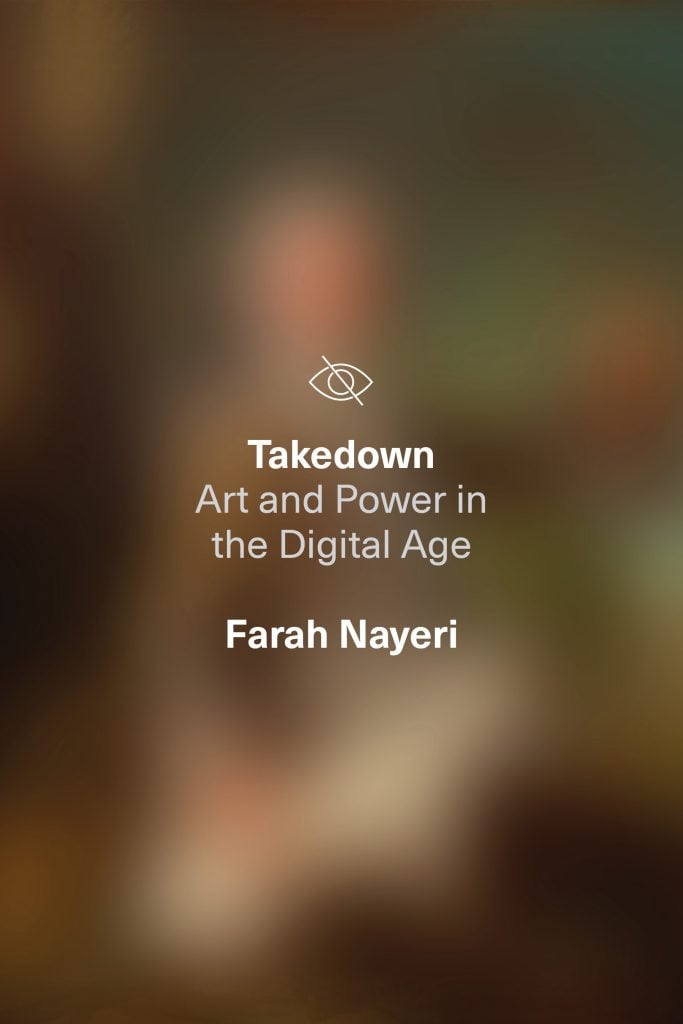

Activists from Just Stop Oil glued their hands to the frame of the painting The Hay Wain by English artist John Constable and covered it in a mock ‘undated’ version including roads and aircraft to protest against the use of fossil fuels at the National Gallery in London on July 4, 2022. (Photo by CARLOS JASSO/AFP via Getty Images)

Another mythical masterpiece, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, has endured a barrage of vandal attacks in the last century—more than any other single work of art. Her status as the world’s biggest art celebrity has turned her into a billboard (or dare I say a dartboard?) for attention-seeking vandals, who have pelted and pummeled her repeatedly.

In 1956, a vandal threw acid at the Florentine noblewoman. That same year, a Bolivian painter hurled a rock at her, damaging a piece of pigment next to her left elbow (which was subsequently painted over).

She was then shielded by glass, but the vandalism continued. In 1974, while the Gioconda was on loan to the Tokyo National Museum, a disabled woman protesting the museum’s poor accessibility sprayed red paint all over her. And in 2009, a Russian woman furious at her failed French citizenship application threw a cup bought from the Louvre boutique at the Mona Lisa; it hit the bulletproof glass and smashed into pieces.

In an attack last May—images of which were viewed by millions of people around the world—a climate activist disguised as an elderly lady rolled up to the Mona Lisa in a wheelchair, then splattered a cream cake all over her glass pane, exhorting those present to think of the planet.

Vandalized masterpieces have so far survived these attacks. But in their scramble to attract attention, activists of one persuasion or another may end up permanently damaging a great work of art.

Perhaps some of them view art as the twee pursuit of the idle rich, or the pastime of stuffy elites. But great pieces of art and heritage belong to all of humanity. When one of them is wrecked, a part of humanity dies. Eco-activists are right to want to rescue humankind from destruction. But one of these days, their activism may end up damaging the common heritage of humanity.

Meanwhile, recent art attacks may actually be backfiring, hurting the cause that they set out to serve.

Phoebe Plummer and Anna Holland from Just Stop Oil addressing the public after throwing tomato soup on Vincent van Gogh’s Vase with Fifteen Sunflowers (1888). Screenshot from @damiengayle.

Over the weekend, I headed over to the National Gallery to check up on Van Gogh’s Sunflowers, two weeks after tomato soup had been splashed all over the painting’s ultra-slim and barely visible glass covering. I noticed that every few minutes, a new swarm of smartphone-wielding visitors formed around it, taking snaps of the would-be crime scene.

Many seemed to be there just to see the Van Gogh, capture it on camera, and look out for any signs of damage. In other words, the tomato soup episode seemed to have drawn massive attention to Van Gogh, to his Sunflowers, and to the National Gallery—rather than to the global climate emergency.

I walked up to two young women who were taking snaps of the painting and asked them how they felt about the attack. “It’s not right to throw soup all over a masterpiece as a way of denouncing climate change,” said one.

It’s a message that I hope the perpetrators will heed.

Farah Nayeri is the author of Takedown: Art and Power in the Digital Age and a culture writer based in London. She also hosts the CultureBlast podcast.