Opinion

The Warren Kanders Protests Have Opened a Pandora’s Box About Ethical Museum Funding. Where Do We Go From Here?

As the protests of funding add up, they pose difficult questions about the art system as a whole.

As the protests of funding add up, they pose difficult questions about the art system as a whole.

Ben Davis

In the popular imagination, calling someone a “modern Medici” is a synonym for “visionary patron of the arts.” That association itself shows how much good PR art patronage buys you.

You don’t think “the Pope’s banker.” You don’t think “hated oligarch.”

By the late 15th century, the Medici banking empire had amassed so much power that they and their cronies essentially ruled formerly republican Florence. Amid broader political chaos on the Italian peninsula, when Lorenzo the Magnificent was succeeded by his talentless and unlikable son Piero, the Medici capture of power became so unbearable that a movement arose to cleanse Florence, led by crusading populist friar Girolamo Savonarola.

By that time, Medici rule had fixed the association of artistic ostentation with injustice in the public mind. So when the family was exiled and Savonarola declared a more broadly enfranchised government in 1494, art was caught in the fallout. Savonarola would preach the need for a “Great Renovation,” a return to the austere truths of the Gospels. Art, books, and cosmetics alike were torched in his “Bonfire of the Vanities,” on Shrove Tuesday, 1497.

The inequities of Medici rule had made Savonarola’s message of the need to purge the city of corruption so convincing that even numerous artists—including Botticelli, who had made his name via Medici patronage with paintings that gave sensual life to pagan antiquity—signed up for his moral crusade. Legend has it that a number of Botticelli’s paintings were sent to the flames.

This story about the ur-patrons of the European tradition is worth remembering as scandals about art patronage pile up today. It is easy to say, “oh, art has always been supported by dubious wealth.” But it has to be remembered that when injustice accumulates and society starts to come apart, history tells us that the system will break, and art will not be spared.

Keeping track of all the scandals around museum patronage in the United States in the last few years is no easy feat. There are scandals over real estate money, prison money, oil money, funding by climate change deniers, funding by supporters of far-right causes in general, Koch Brothers funding, and more.

And as they multiply, the scandals begin, more and more, to become less about individuals and more about the system. Sometimes voiced out loud but mainly behind the scenes, the question for museums is: Where will the money come from?

Supportive observers, meanwhile, are asking the question: Can we win? What are the odds here? Given the sheer number of crises and scandals and potential places to volunteer your time, it’s logical that even the most politically engaged might ask questions about the time and resources and strain on relationships that a campaign will take, compared to the potential symbolic value.

Determined protest can shame individual donors into leaving museum boards if staying becomes really, really bad PR for them. The ice seems to have been broken, as a variety of museums and other institutions recently announced that they would no longer accept Sackler money.

Protestors at the Guggenheim Museum stage a “die-in” to protest Sackler funding. Photo: Caroline Goldstein.

But it’s worth being sober about the fact that there is a difference between the struggle around the Sacklers, who are being sued simultaneously by more than a thousand cities and counties for their role in one of the worst public health crises in history, and the struggle around the patronage of the Whitney Museum by Warren Kanders, who became a target of protest after tear gas made by his company, Safariland, was used at the US-Mexico border.

Let’s be clear: Kanders makes money from products that have inflicted crippling pain on little kids fleeing poverty and violence. That is enraging.

Yet, today, if you Google “Sackler” you will find hundreds of stories about the family’s misdeeds—so public and pervasive that even a perfectly innocent man named David Sackler in New Jersey has been targeted by protesters—with a few about the museum protests mixed in. But if you Google “Safariland,” you will get only stories about the museum protests, primarily from the hot house of the art media, plus corporate PR about the company’s affairs.

In the wake of the wrenching images of attacks on refugees at the border in November 2018, activists facing a government set on its pitiless agenda looked for symbolic avenues to press, and found one in shaming the maker of the tear gas used. Now, however, the campaign against Kanders at the Whitney is in the position of keeping alive an issue that has waned from the broader conscience in the scandal-of-the-moment theater of contemporary politics (though, of course, fresh attention could explode at any moment).

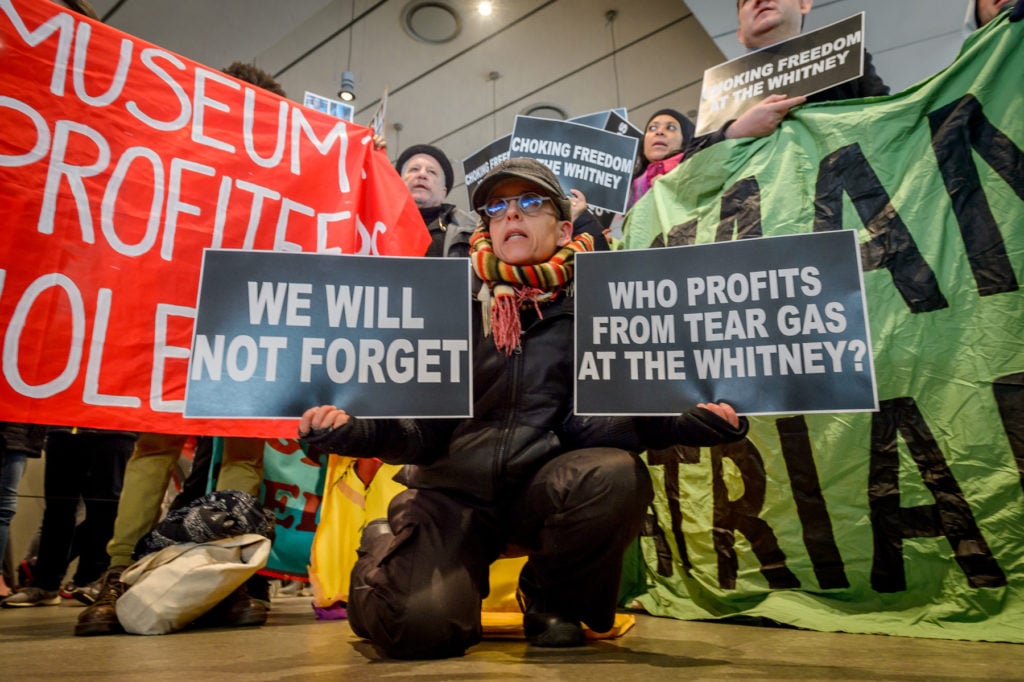

Activists stage a protest in the lobby of the Whitney Museum of American Art to protest and demand the removal of the museum’s board of directors Vice Chairman Warren B. Kanders. Photo by Erik McGregor/Pacific Press/LightRocket via Getty Images.

Without the kind of wider pressure of the Sackler case, I don’t think museum higher-ups are close to budging. They very well know that opening that particular can of worms would lead to questions that would inevitably undermine the entire, precariously balanced structure of arts funding in the United States.

Just to give a sense of how little potential negative symbolism matters compared to the structural realities of art patronage: Kathy Fuld remains a fixture of the MoMA board to this day. She is most famous for going on $10,000 shopping sprees while her husband, Dick Fuld, crashed the world economy as CEO of Lehman Brothers. In 2009, she “purchased” a $13 million house from her husband for $100 in what was widely seen as a brazen asset-hiding deal—even as Lehman’s chaotic bankruptcy and the shady mortgage market that it had enabled caused hundreds of thousands of people to lose their own homes in the foreclosure crisis, touching off a world-historic economic disaster whose effects have shredded the social fabric.

Even the new, beloved National Museum of African American History and Culture, a government-run branch of the Smithsonian Institution, opened boasting copious private support. In addition to funding from firms like Boeing and Walmart, this included $10 million from David M. Rubenstein, co-founder of the Carlyle Group—a company that was in the news for a blip last year when comedian Hasan Minhaj connected the dots to show how it profits from components for the Typhoon fighter jets used by Saudi Arabia in its butchery in Yemen.

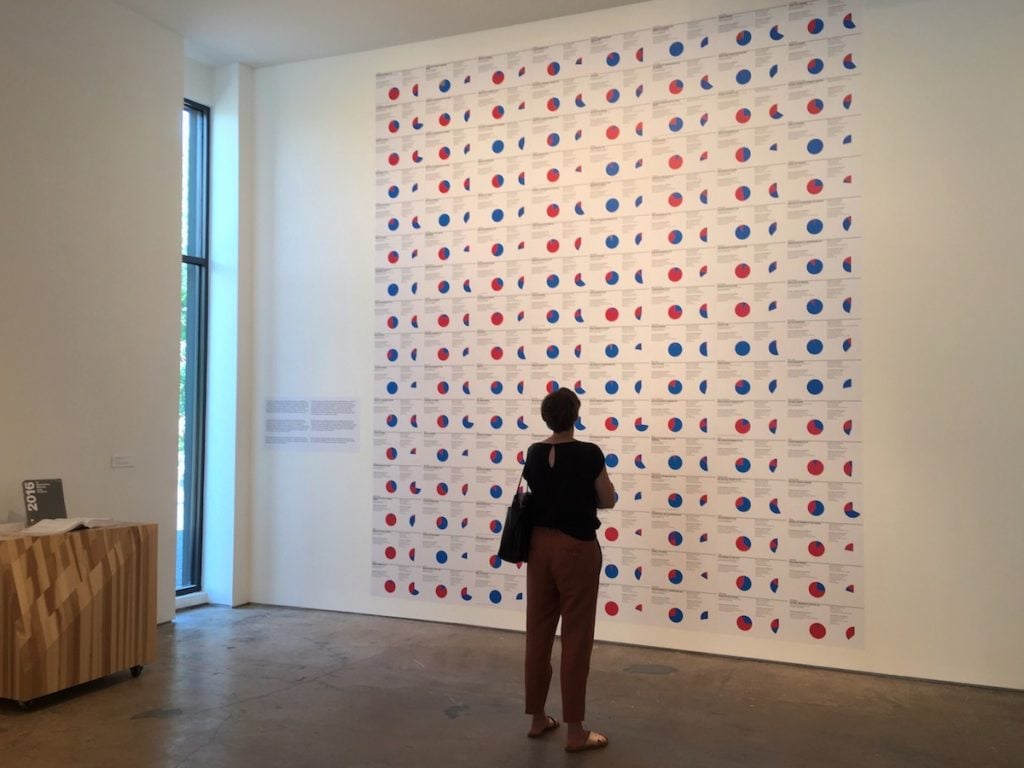

How did we arrive at this parlous point? Concerns over ethical funding aren’t new in the US: Hans Haacke’s On Social Grease is from 1975! That work, a classic of institutional critique, presented itself as a series of ceremonial plaques, inscribed with quotes from businessmen and corporate types on the good PR value of arts patronage.

Since that date, bipartisan neoliberalism in the United States has led to tremendous increases in social polarization, precarity, and just general anger at the unfairness of the country’s economic and political life. Supporting art has been seen as an unqualified good, more or less. But particularly in the period since the 2008 financial crisis, its ability to play that role has dimmed as the ugliness of the system is ever more plainly exposed.

Installation view of Andrea Fraser’s 2016 on view at SITE Santa Fe, documenting the political contributions of board members of US museums.

Looking in from outside, maybe you wouldn’t get a sense of crisis at the country’s big art institutions themselves. In fact, a few years ago, the Art Newspaper released a study showing that, in the period from 2007 to 2014, the United States dwarfed all other countries in terms of museum construction and expansion. In that Great Recession period, US institutions spent close to $5 billion—as much as the 37 other countries in the study combined.

What accounts for that leading position? The interaction of two factors:

1) The post-financial crisis period has been a great time for private wealth, with inequality soaring.

2) The US art system, in comparisons to its peers, is exceptionally linked to private wealth.

Donations from private sources are the biggest source of support for US museums—far bigger than admission fees. In an age when, across the world, the balance has tipped towards the ultra-wealthy, the arts system that most directly courts that wealth wins. The US in particular is heliotropically oriented towards it—a fact symbolized by all those donor names plastered on those new museum walls, and stairways, and fountains created in the last decade.

And while this is sometimes framed as a matter of “public” versus “private” funding, it’s also important to note that a good chunk of the total already comes out of the public coffers anyway, because charitable donations are encouraged in the form of tax breaks, amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars of foregone tax revenue. As the NEA frankly stated in a report, the tax break is “the most significant form of arts support in the United States”—far larger than direct government support, unlike in most European countries.

At the Whitney, the group Decolonize This Place has led the demonstrations against Kanders. I have not always agreed with the targets of Decolonize’s museum protests (I find scholar Chika Okeke-Agulu’s criticisms of their decision to picket the Brooklyn Museum for hiring a white curator to work on its African art collection convincing). But, in general, they draw together many activists whom I admire, and raise vital issues.

In their literature, Decolonize does have a systematic take on the problems of museum funding that goes well beyond Kanders—a fact that may or may not help get rid of him, since framing their grievance as being around problematic wealth itself rather than specific crimes makes it clear in advance that the museum cannot win by disassociating itself from a single implicated funder.

In fliers passed out during their nine weeks of protest leading up to the Whitney Biennial, Decolonize called for the museum to be reimagined as an institution “run by and for workers and their communities as a cooperative platform rather than a money-laundering operation for the ultra-wealthy.”

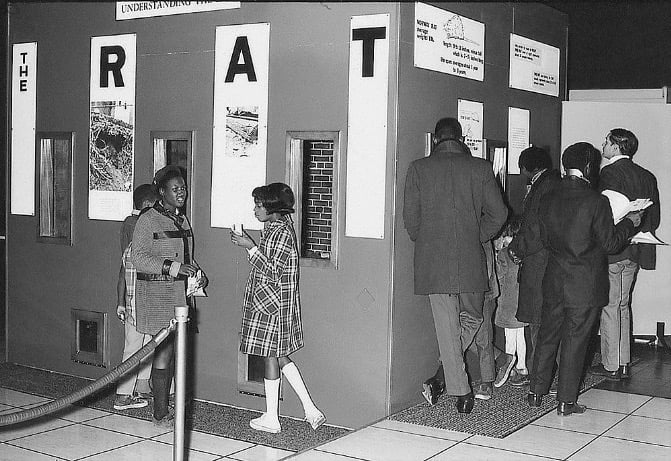

“The Rat: Man’s Invited Affliction” at the Anacostia Neighborhood Museum, November 16, 1969. Image: Smithsonian Institution Archives Image.

The idea of the museum as an experimental co-op fires the imagination. This would be something perhaps more in the “community museum” tradition, exemplified by the original Anacostia Neighborhood Museum in Washington, DC, growing out of Civil Rights ferment and curated with community collaboration. (Its 1969 show called “The Rat” drew together information about the number-one neighborhood pest, calling attention to a problem and giving practical information on “how NOT to create rat habitat!”)

Such a transformed museum would not be anything like the museum as we think of it today. It would likely have no high-profile touring shows or pricey permanent collections; it might not draw the tourist bucks the Whitney does today, or serve the same number of visitors; it might not have the same kind of research facilities or educational programs. It certainly would not have the same galas, dripping with luxury and glamor.

I’m actually willing to give a lot of that stuff up. New York’s art scene is over-centralized in mega-institutions. A more responsive art scene would focus on a greater variety of diverse local institutions—probably the kinds of local institutions that don’t require the kinds of mega-investments that tie them to mega-donors.

Nevertheless, even in such a scenario, the question of where the money comes from remains—particularly at a moment when museum workers across the country have already been increasingly protesting being scandalously underpaid. Without being able to answer this question for myself, I find it hard to imagine a movement that actually grows, as each successful protest against a donor only increases the power of remaining donors in the overall funding equation.

The more systematic the critique of private funding becomes, the more the answer will also have to be systemic. In addition to representing a stand against war profiteers or peddlers of addiction, saying that museums should aim to free themselves of tainted money has also to be about advocating for a different arts funding regime that directly redistributes wealth to pay for art, instead of leaving it to noblesse oblige.

Incidentally, that solution also solves the nagging problem that demanding that unsavory people stop funding museums has the unwanted side effect of freeing their money to go to more unsavory causes.

I know there are questions about what a reshaped art system might best look like, or what kind of movement you’d need to put together to make it happen. There are questions about whether it is swimming against the tide of history. Eroded by austerity, European museums have actually, as the New York Times put it, been nudging towards “the American way of giving” for some time. Maybe the increasingly insistent protests over “toxic philanthropy” and “reputation washing,” and how they are adding up to undermine US museums’ mission, serve a double purpose as a cautionary tale on the international stage.

But this is a case where advocating for what seems radical is actually the most reasonable. If we don’t find some way to course correct and redistribute both wealth and power, the pressures on art are only going to increase, because a bigoted nationalism is ascendant, the police state is expanding, “deaths of despair” are on the rise, the environment is coming apart—and some of the same names on the museum walls are stamped all over these things too. If that trajectory runs its course, history suggests that the choice between Team Medici and Team Savonarola—between overlooking the dark side of patronage or deciding that art as a whole is mere decadence—is only going to be posed more and more starkly.