Artist Gideon Rubin Redacted Nazi Texts, Then Installed Them in Sigmund Freud’s Home

Taylor Dafoe

Can art engage with historical propaganda without becoming propaganda itself?

Artist Gideon Rubin explores this question in his exhibition, “BLACK BOOK,” on view now at the Freud Museum in London, located in the house the pioneering psychoanalyst occupied after fleeing from Nazi-annexed Austria.

For the exhibition, Rubin collected rare Nazi paraphernalia and altered it beyond recognition. His works are not just on walls and in vitrines but planted throughout the home—on bookshelves and tables and in Freud’s study, next to his infamous couch—as if they belonged to the doctor himself.

Rubin, an Israeli-born artist currently living in London, is best known for his paintings of faceless figures, often based off of old found photographs the artist collects. The works in “BLACK BOOK” are similar in that they engage directly with vintage material, however, the element of anonymity is gone. Rather than decontextualized depictions of unidentified figures culled from family photo albums and other unremarkable materials, the works in “BLACK BOOK” are all about context and origin. The gesture of altering historic documents—removing faces or redacting information—is less about the whitewashing of time, and more about rewriting history. Evoking Freud, the works play on the psychologist’s theories about repression and our tendency to block out certain memories from our psyche.

Installation view of “BLACK BOOK” at the Freud Museum (2018). Courtesy of the Freud Museum.

The seeds of the exhibition first began a couple of years ago when Rubin, an Israeli Jew whose maternal grandparents also had to escape the Nazis in the late 1930’s, decided to turn from anonymous photos to material connected to his own sense history and identity. He turned to eBay, looking for authentic Nazi paraphernalia. Or, more accurately, his wife Silia Ka Tung, did. A fellow artist and more computer literate than Rubin, Tung scoured the auction site for artifacts.

A week later, a package of old magazines from Nazi East Germany arrived at his house, replete with pictures of Hitler and swastikas. “It freaked me out,” Rubin says. “The first couple of days I was washing my hands every time I touched them because I was so repulsed by the subject matter.”

Installation view of “BLACK BOOK” at the Freud Museum (2018). Courtesy of the Freud Museum.

He began working with the magazines in the way that he usually works with vintage source material, using the imagery as the basis for paintings. He was interested in the work but also confused. “I didn’t know why I was doing them,” he recalls. “I didn’t understand how I could be so drawn to them and repulsed by them the same time. But when I started covering the Nazi emblems and the pictures of Hitler, it made me feel better. I thought that was a good enough reason to continue on.”

And so he did. He expanded his research, asked his wife to purchase more artifacts, and made a trip to visit Freud’s original home in Vienna from which he was forced to flee. But soon after, Rubin ran into his biggest challenge yet.

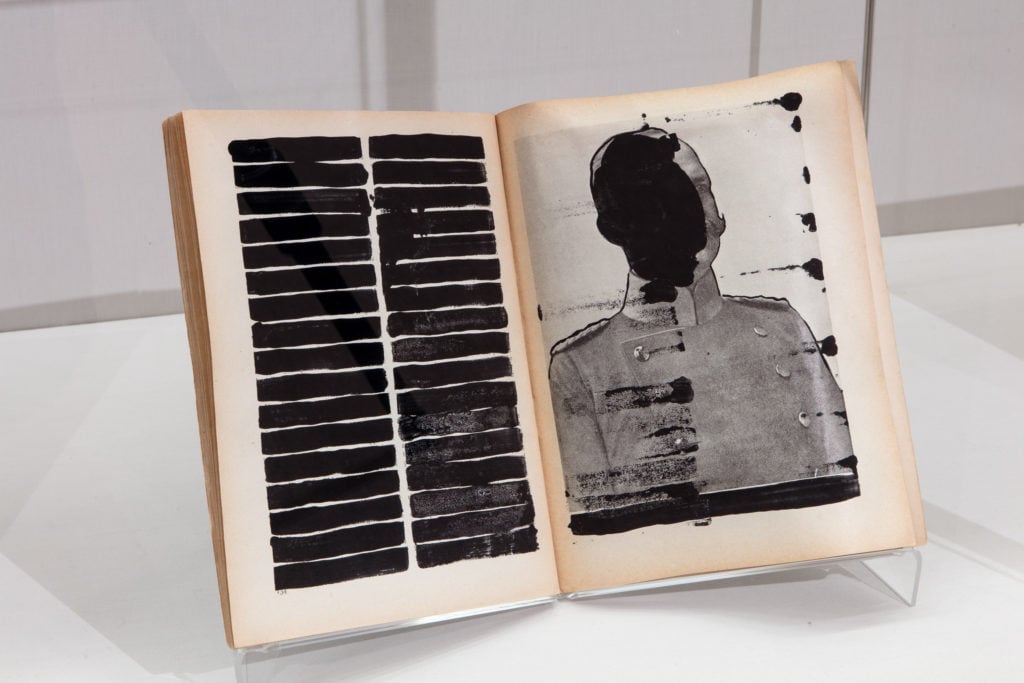

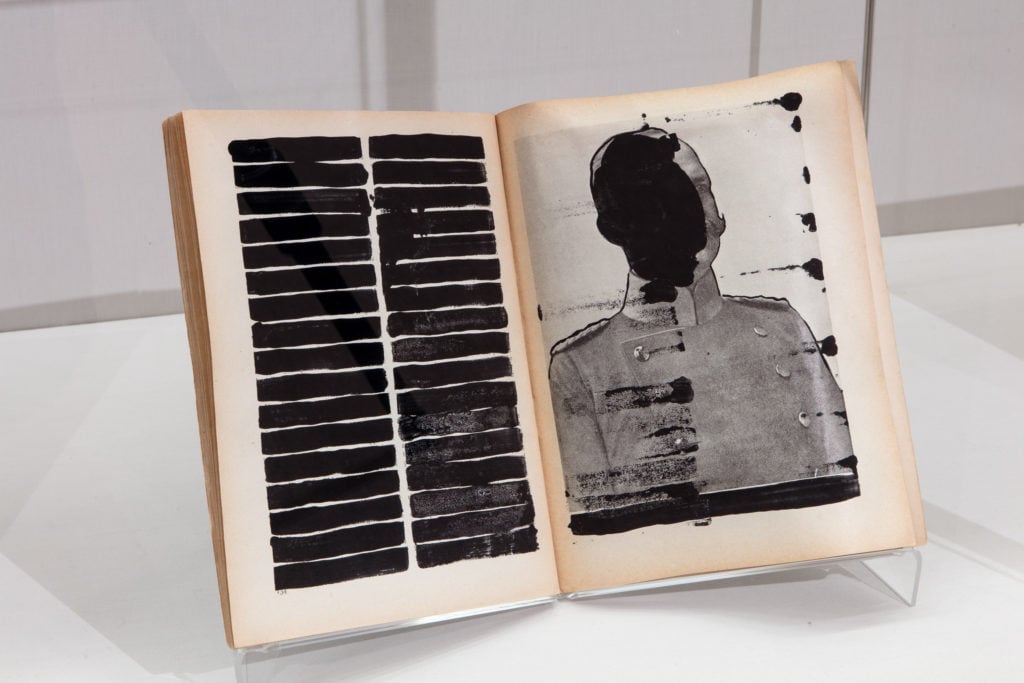

Gideon Rubin, BLACK BOOK (2018). Courtesy of the Freud Museum.

“One day I got this package in the mail,” Rubin recalls. He went downstairs to get it, and his wife told him that she had found something “great.” “I opened the packaged, and a chill ran down my spine.”

It was a serialized first edition of the English translation of Mein Kampf, Adolf Hitler’s autobiography, published in the UK in 1939 (just one month after Freud’s death).

“’This is way too dirty for my paintings,’ I told my wife. ‘I can’t even have this in my house. I need to burn it,’” he said, already thinking about the possibility of being under government surveillance for owning such a thing. But his wife encouraged him to keep it and to use it in his work. “I thought that it was the most fucked up idea I had ever heard. ‘I’m never going to do that,’ I told her.”

But sure enough, a week or so later, Rubin pulled out the book. He began working directly on the pages, redacting text, and altering faces. The resulting work—with each and every word, symbol, and person blacked out—makes up the current show’s titular piece, BLACK BOOK. It’s installed in a case in the museum among the work he did with propagandist magazines and a series of paintings on canvas, linen, and paper.

Installation view of “BLACK BOOK” at the Freud Museum (2018). Courtesy of the Freud Museum.

After BLACK BOOK was done, the initial questions that Rubin had to confront still plagued him. The Nazi materials, while representing something terrible, were nonetheless historic documents that should never be forgotten. How could he reconcile the fact that he’d altered them, even if the experience was personally rewarding?

“When I finished the last page, I looked at it and realized that it wasn’t Mein Kampf anymore,” Rubin says. It was my BLACK BOOK. I discovered that blacking out is not a subtractive gesture; it’s an additive one. You never actually erase anything; you add something that covers it up. It’s similar to memory, and how the brain works. Memories never go away, they just move or morph or become covered by another one.”

“You can’t negate the life of things that have come before, you can only create something new.”

Installation view of “BLACK BOOK” at the Freud Museum (2018). Courtesy of the Freud Museum.

“BLACK BOOK” is on view at the Freud Museum through April 15, 2018.