A Memorial Exhibition at ACA Galleries Grapples with Richard Hambleton’s Complex Legacy

Taylor Dafoe

Richard Hambleton is having a moment. His auction sales have spiked in recent months; he’s the subject of several shows, including a recently-opened retrospective in London (the opening of which drew a number of celebrity visitors); and the 2017 documentary about his life, Shadowman, is now streaming online after a buzzworthy turn on the festival circuit.

Tragically, of course, Hambleton isn’t alive to witness any of this. The so-called “Godfather of Street Art” passed away a year ago this October. And yet, in one way at least, this sad irony is fitting for a talented man, who, by all accounts, was held back from art stardom because of only one major obstacle: himself.

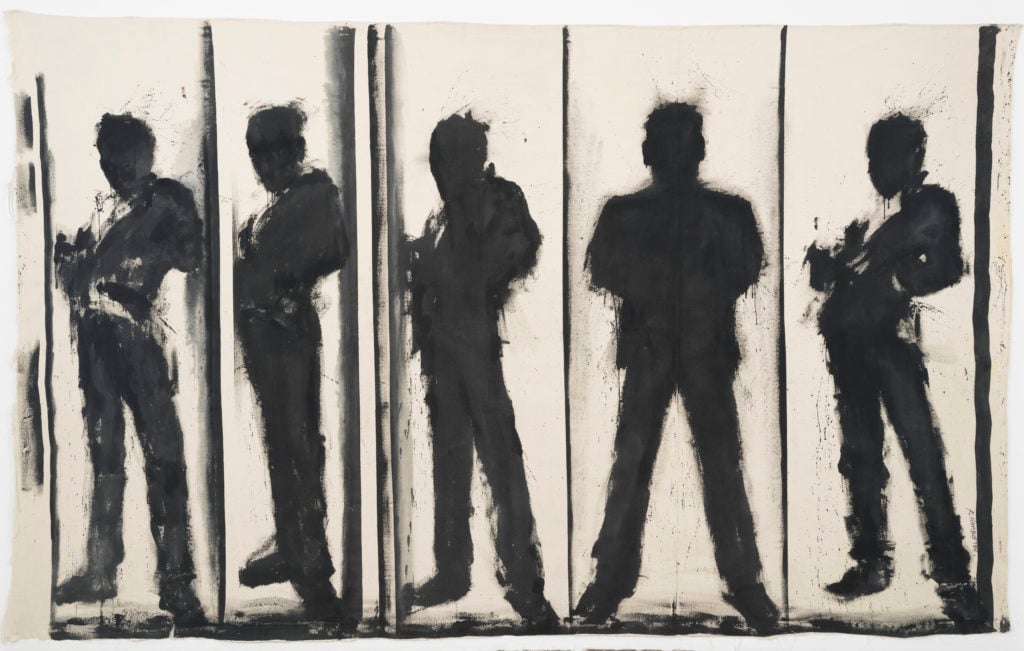

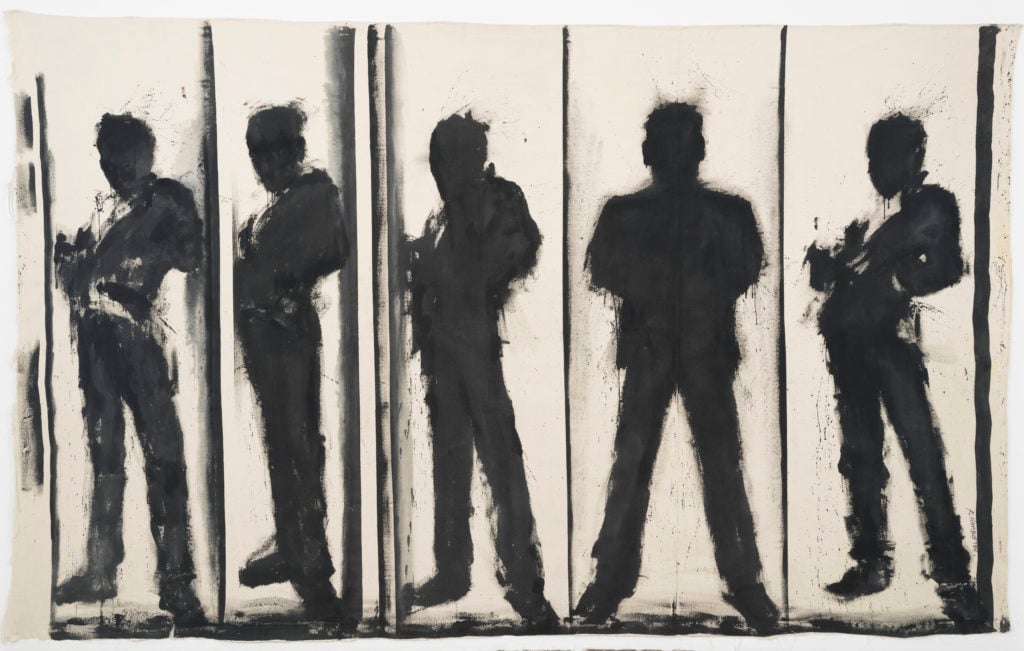

Installation view of “Richard Hambleton: Eternity,” 2018. Courtesy of ACA Galleries.

A longstanding heroin addiction yielded a number of self-destructive habits for the artist, including trading works for a quick fix (sabotaging his own market in the process) and relying on a revolving crew of friends, fellow artists, and gallerists for workspace. By the end of his life, the combination of extended drug use and skin cancer had cratered half his face, causing him to look like a real-life manifestation of one of his shadowy street works.

Indeed, it seems that everyone who knew Hambleton has a story about his addiction. However, for the ones that knew him the best, his tragic story won’t have the staying power that his work does.

“Ultimately Richard’s legacy will be his artwork,” says Mikaela Sardo Lamarche, director of ACA Galleries in New York, the site of a memorial exhibition to the late artist on view now. “The paintings themselves speak to viewers in a very immediate, exciting way—he was able to translate the energy of the street into dynamic, gestural compositions that play with the intersections between figuration and abstraction. His oeuvre deserves more study and as time goes on institutions, curators, and galleries will begin to unravel the complex artist that Richard was.”

Richard Hambleton, Horse and Rider (Black and Gold on White) (2016). Courtesy of ACA Galleries.

The ACA exhibition, titled “Eternity,” brings together paintings from two of Hambleton’s best-known bodies of work: “Shadowmen” and “Horse and Rider.”

Born in Vancouver in 1952, Hambleton first garnered the attention of the art world in the late ’70s, when, alongside Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Haring, he turned the rundown buildings of downtown New York into his own personal canvas. He began producing “Shadowmen”—his series if inky-black silhouettes, eerie and mysterious—in the early ’80s, first on the streets and buildings, and then on canvases in-studio. The Shadowman became the artist’s signature; it still is today.

Within a couple of years, the “Shadowmen” evolved into another one of Hambleton’s other well-known series—“Horse and Rider.” Inspired by the “Marlboro Man” cigarette ads, they depicted a shadowy figure atop an equally shadowy bronco mid-buck.

Richard Hambleton, Horse and Rider (red and black) (2005). Courtesy of ACA Galleries.

Lamarche, who has collected and sold Hambleton’s work since 2012, knew right away that these series would make up ACA’s extensive show.

“Since the exhibition was a memorial to the artist, the aim was to show the best quality works possible,” says Lamarche, who borrowed several paintings—including many the gallery once sold—from private collections. “The two series were subjects that the artist returned to over and over again throughout his career and they are among the strongest paintings in his artistic output. Our goal was to demonstrate his importance to the canon of American art.”

Installation view of “Richard Hambleton: Eternity,” 2018. Courtesy of ACA Galleries.

“Richard Hambleton: Eternity” is on view at ACA Galleries through October 6, 2018.