See Works by 5 Artists in the Artnet Gallery Network That We’re Watching This Month

Artnet Gallery Network

At the Artnet Gallery Network, it’s our goal to discover new artists each and every month. We search through the thousands of talented artists on our website to select a few we find particularly intriguing right now.

This month, we’ve chosen five artists working in Los Angeles, Berlin, and beyond, from one artist exploring representations of cultural identity to an American artist investigating the various meanings behind patterns.

Below, discover five artists we’ve got our eye on this February.

Celia Rakotondrainy, Yesterday Was Tough but Tomorrow Will Be Better (2019). Courtesy of Artistellar.

Looking at Paris-born, Berlin-based painter Celia Rakotondrainy’s portraits can feel like you’re viewing the world through a kaleidoscope—her figures appear as if mirrored, their reflections folding into one another. The artist, who is of Malagasy descent, says her portraits are an attempt to capture the many identities contained within one individual’s identity, and how that identity’s construction, in the end, is not unlike a painting—a construction.

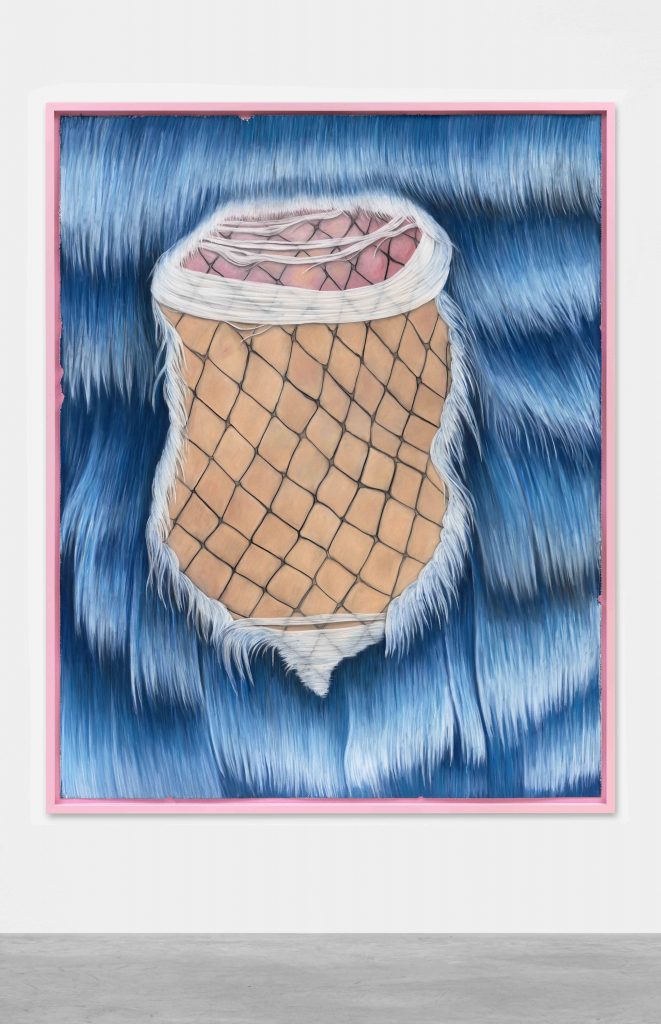

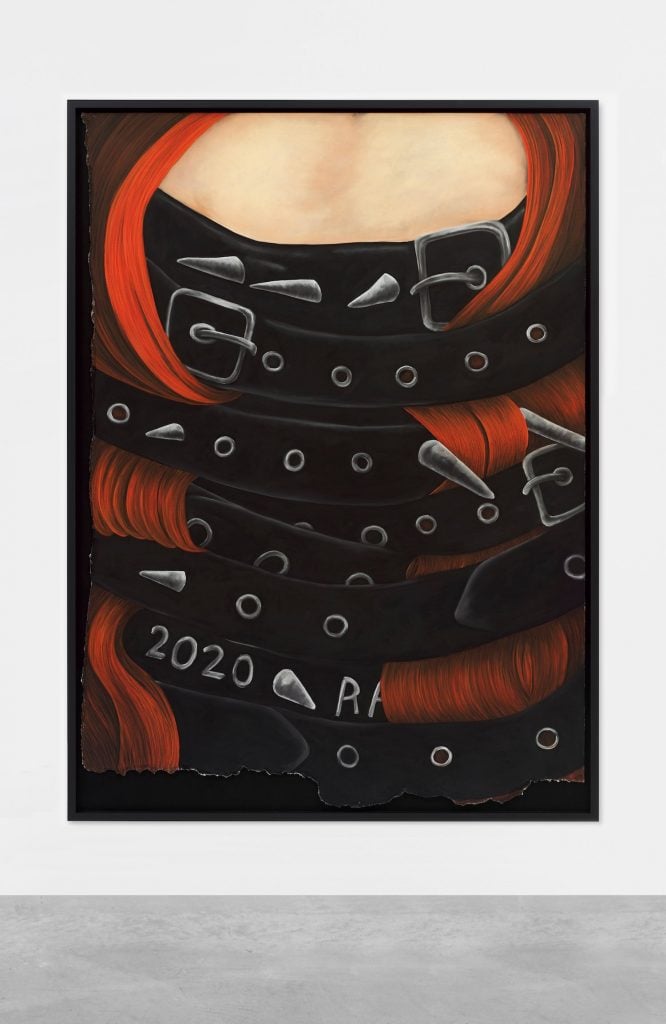

Rebecca Ackroyd, Garden Trawler (2020). Courtesy of Peres Projects.

A sense of urgency predominates British artist Rebecca Ackroyd’s works, and in “100mph”—the title of her current exhibition at Peres Projects in Berlin—that energy reaches a fever pitch.

In the new works, Ackroyd renders close-up, cropped-in images of ripped tights, leather studs, coils of hair, which together hint at some larger unseen unfolding narrative. One could imagine these are snippets from the life of an unknown protagonist as she navigates through an urban dystopia.

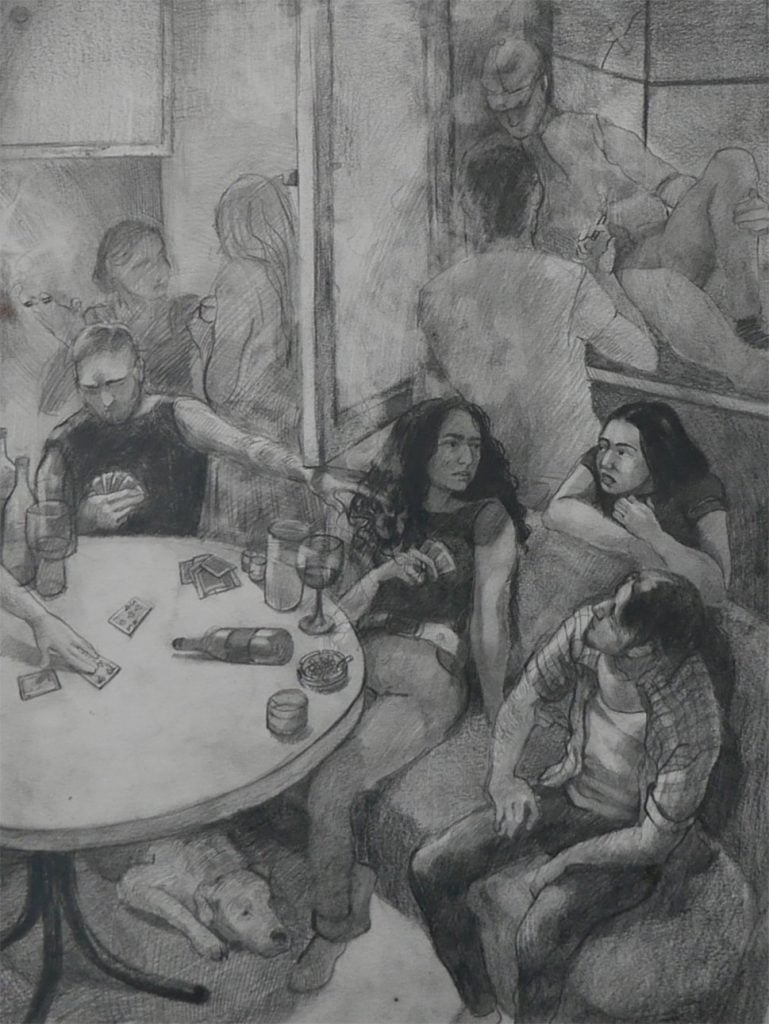

Maria Chepisheva, Corona Traum (2020). Courtesy of re|space gallery.

Bulgarian-born artist Maria Chepisheva alternately works from her real-life surroundings to other times entirely, including from her imagination. Her figurative works interestingly imagine compositional space. Right now, a few of her pencil on paper drawings are on view in a group show at Berlin’s re|space gallery. These works, made during the last year of quarantine, longingly imagine people gathered together in bars, drinking and making merry, seemingly unaware of the concerns of our time.

Sebastian Herzau, Totilas (2021). Courtesy of Filser & Graf.

Mid-career German artist Sebastian Herzau’s figurative paintings often isolate his subjects against neutral backgrounds. Often in his portraits, he crosses off the faces of his figures with bold, marker-like strokes. Other times, his scenes appear blurred, as though they appear behind a piece of foggy glass. In his recent painting Totilas, pictured here, Herzau paints an assemblage made of matchsticks, a chestnut, and an acorn put together to vaguely resemble a horse. The title, Totilas, makes a witty reference to the famed horse racing steed Totilas, who died last year.

Alex Heilbron, High Esteem (2020). Courtesy of Meliksetian / Briggs.

At first glance, Alex Heilbron’s paintings appear to be constructed of tightly ordered patterns that form grids of floral motifs, geometric shapes, and rigid lines, placed atop underlying imagery of female figures. A closer look reveals a more porous approach, with background and foreground often weaving together in individual passages, and collapsing into the images in one space The works, which quietly interweave female forms and decorative patterns hint at the unseen histories of women’s domestic and textile work, and, in creating one self-referential trope, seems to beg for revaluation of their meanings.