British Painter Clare Woods Talks About George Orwell, Depicting the Body in Pain, and Her Habit of Collecting Ideas for Titles

Katie White

“For me, it’s important to hear what George Orwell has to say from the grave,” says the painter Clare Woods.

Her new exhibition, “Doublethink,” at Simon Lee Gallery in London, takes its name from a term coined by Orwell in his dystopian classic, 1984. “Doublethink,” Orwell writes, is “the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.”

This kind of mind-bending is both a sign of the times and, for Woods, an artistic predilection. Over the past 25 years, she has defined a distinct painterly language in which the boundaries between the familiar and the strange, the real and the uncanny, sway—and often to unsettling results.

Clare Woods, The Cook (2019). Courtesy of Simon Lee Gallery.

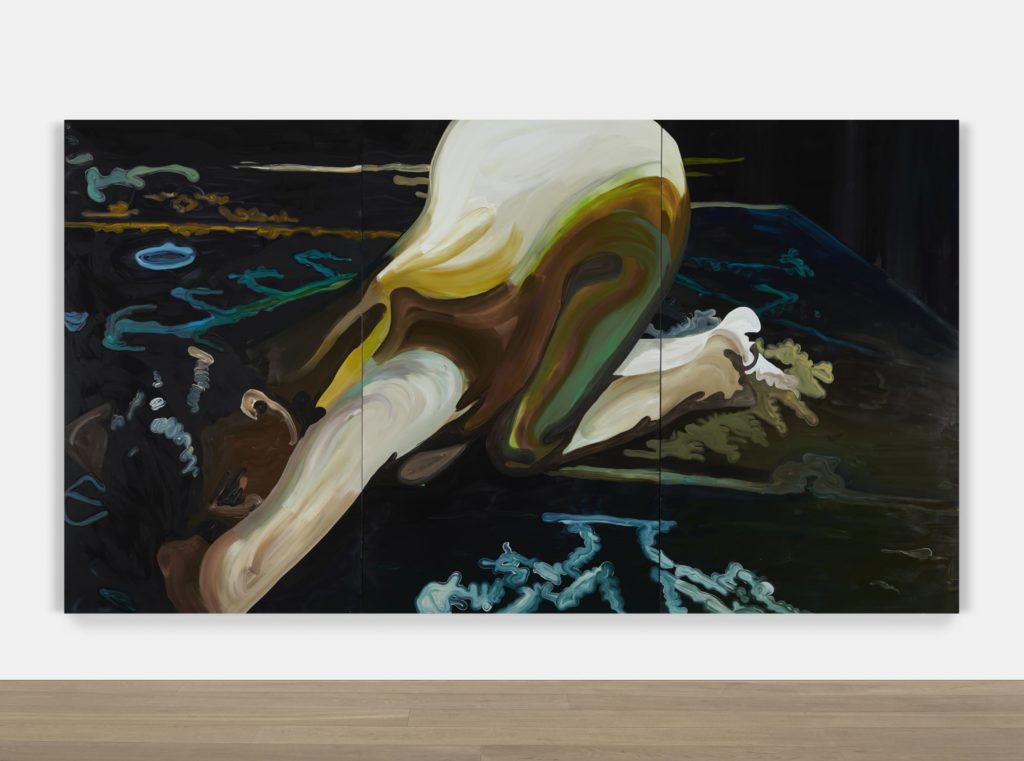

After many years focusing on landscapes, Woods has recently brought her sensuous and disorienting touch to the figure. Working from photographs, as has long been her practice, she translates human figures into disorienting tangles of limbs and acidic-tinged hues that conjure up ideas of decomposition, death, and the quite literal breaking apart of the figure.

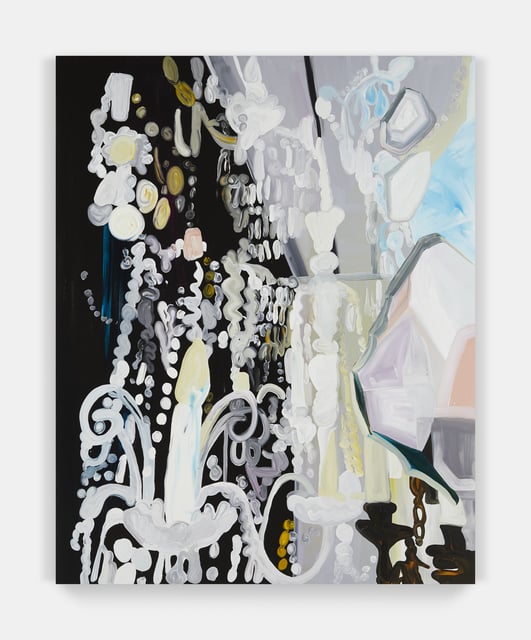

But these macabre scenes are just one thread in her narrative. Alongside these, the exhibition includes recent paintings of viscously petalled flowers and a darkly lit chandelier in an ornate, gilt-framed mirror—which together create a reverberating discord between beauty and the grotesquery.

Recently, we caught up with Woods to talk about why she started painting the figure, how illness informs her practice, and where she finds the titles for her paintings.

Clare Woods, Notes on Madness (2019). Courtesy of Simon Lee Gallery.

After many years painting landscapes, you’ve more recently started depicting the human body. How did that transition come about?

I worked in landscapes for a long time, mostly with enamel paint. I started to try working with oil and when I did the source material began to change as well. Around 2011, I had been painting rocks, and then slowly started painting sculptures by Henry Moore and Barbara Hepsworth. I have a BA in sculpture and I’ve always been interested in capturing these qualities.

As you know, I was painting from photographs. All of my work comes from photographic source materials where I make drawings of the photographs and strip a lot of the details away. The line drawing is what I’m left with. Then I’m almost trying to make the object back again with the paint, I guess. So I started painting these sculptures then realized I could paint heads or hands or whatever. It was a big leap, but it was very organic.

Clare Woods, Peace (small) (2019. Courtesy of Simon Lee

How do you find your source images?

I’ve been collecting photographs for 25 years. Sometimes I’ve had a photograph for years and years before I realize I can paint it, or know how to paint it. It’s not me looking for them as it is me finding them. It’s a very instinctive. There’s something about photographs. There’s always some conceptual interest that’s not just how it looks, but how it feels. Also there’s the challenge of being able to paint something that exists in real life. That’s what the basis has to be. Most of the photographs are black and white, found imagery, or photographs I take myself.

Clare Woods, Memory Hole (2019). Courtesy of Simon Lee Gallery.

Do you think there’s a reason you’re more attracted to black-and-white photographs? Is there more room for imagination?

When I was painting landscapes, I was actually in the landscape photographing it myself. I knew what the colors were, I knew how it smelled, how it felt. I had an understanding. Whereas when I started these black-and-white images of sculptures that I’ve never even seen, I didn’t know how big they were, their color… it was a fugue state to project my own colors and to use the image without knowing the dimensions, or the smell, or feel, or its taste. Having no physical understanding of the image, taking a flat image and turning it into something three-dimensional, I suppose, is what interests me.

Your titles can be very evocative. Notes on Madness, Memory Hole… how do you come up with these?

I really like titles—it’s so disappointing when I see a work is untitled. It allows another way into the work. Like photographs, I collect titles; maybe it’s something I read in a book or heard on the radio. As I’m driving along, I see a street name. I’ve got about 5,000 titles collected. When I’m painting, I work flat so in the process, I can’t really see what the image looks like. It’s when I stand it up that I know what it’s going to be called. It doesn’t ever describe what’s in the painting or describe the source material. It’s instinctive. I get it, at least, I know why each one has its title.

Do you have a favorite name that you’ve ever given a painting?

Daddy Witch—I quite like that title. It was a transitional painting that’s in the Arts Cultural Collection.

Clare Woods, Consciously Contemplate (2019). Courtesy of Simon Lee.

In many of these paintings, the body is in turmoil. One painting looks like it’s of a bandaged, burned hand. In another, we see a mouth with most of its teeth missing. What’s attracting you to these images?

Six years ago, I became very ill. I had to have my colon taken out. Over the past four or five years, I’ve spent quite a lot of time being ill. You can’t help but think of your mortality and the more gruesome side of the everyday. I suppose it seeped through because of my personal experience. I never quite know where I’m going. I only make one painting at a time: it’s a very linear process and one painting informs the next. Truthfully, I don’t think I understand my work until it’s done, sometimes months or even years after.

Do you have a ritual to painting? What’s your studio like?

The place where I paint is really big but really cold. It’s not pretty—it’s a big industrial unit. It’s not a nice place to hangout. Since I work flat, I need a lot of floor space. And I work alone. If anyone else is the studio, I can’t paint. Because it’s an industrial space, it can be quite noisy, so I wear noise cancelling headphones. I don’t listen to music or the radio. When I’m painting it’s absolutely silent. If I’m puttering around in the studio doing little things, then I listen to books. I have an office on a mezzanine level that’s got all the books, but on the floor its trestles and paint and paint brushes and trolleys. Its so big everything is on trolleys. That is it though—there’s nothing interesting. When a show is finished and all the work goes, it is just a bare industrial unit, which I really like. Though I do love going to other artists’ studios because, oh there’s a skull and there’s a very interesting this or that. But in mine, there’s nothing.

Clare Woods, The Allnighter (2019). Courtesy of Simon Lee.

Do you like to read or what kind of books do you listen to?

I never used to read, ever. I was only interested in art books or art magazines or catalogues. I do still read a lot of art history, but I’ve been back over the classic novels recently which has been quite interesting. I had to read them in school and I was quite reluctant, but as an adult I actually understand how important these books are. That’s new for me.

I’ve read a lot of George Orwell since Brexit. He writes incredibly well about politics, and describes what was happening during the war. Nothing’s changed. History has come round again. History is very important, art history as well, so I can position myself knowing what’s come before. It’s comforting in a way. Like, that was a really bad time and you lot got through it. I think about that while I’m working.

“Doublethink” is on view at Simon Lee in London through October 6, 2019.