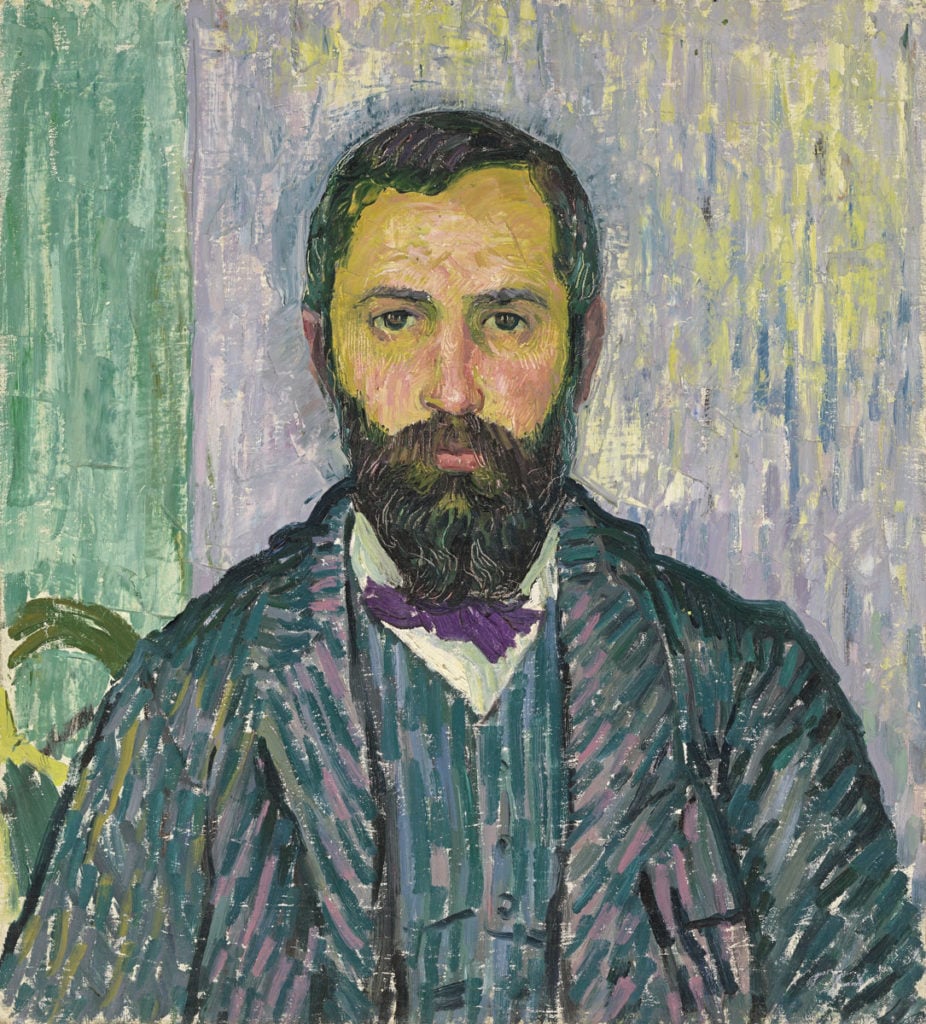

Meet Cuno Amiet, the Most Important Swiss Artist You’ve Never Heard of

Taylor Dafoe

Cuno Amiet is one of the most important Swiss artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, but you probably wouldn’t know it. Since his death in 1961, the misunderstood artist hasn’t been welcomed into the canon like many of his contemporaries have.

A new show at the Roggwil, Switzerland-based gallery bromer kunst is trying to change that. In honor of what would have been the artist’s 150th birthday, the retrospective looks at Amiet’s legacy and considerable contributions to European painting movements.

Bringing together paintings from the bromer art collection and works on loan from collectors and institutions, the aptly titled exhibition, “Cuno Amiet,” looks at the artist’s entire output, from the late 19th century to the mid-20th century, with a particular focus on his early period. It highlights the many styles and mediums with which the artist experimented throughout his 75-year career and identifies four subjects that dominated his work: gardens, harvest, winter, and portraits—especially self-portraits.

Installation view of “Cuno Amiet” at bromer kunst, 2018. Courtesy of bromer kunst.

Amiet was born in Solothurn, Switzerland in 1868. He began painting at an early age, and after studying with Swiss painter Frank Buchser, he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich from 1886 through 1888. It was there that he met his life-long friend, fellow painter Giovanni Giacometti. In 1888–92, both artists moved to Paris to study at the Académie Julian, where they worked with French artists Adolphe-William Bouguereau, Tony Robert-Fleury, and Gabriel Ferrier.

Unhappy with the program at the Paris institution, Amiet left in 1892 to join the Pont-Aven School in Brittany, where he was introduced to the work of Gauguin, Van Gogh, and others in that circle. The experience would have a significant impact on his painting, especially on his use of color, which he embraced wholeheartedly.

“Color meant the world to Amiet,” Wolfgang Zaeh, the director of bromer kunst, tells artnet News. “To a certain extent, it was even more important than the form. He loved life and the beauty of people, nature, and objects. With color, he found a tool to express that affection.”

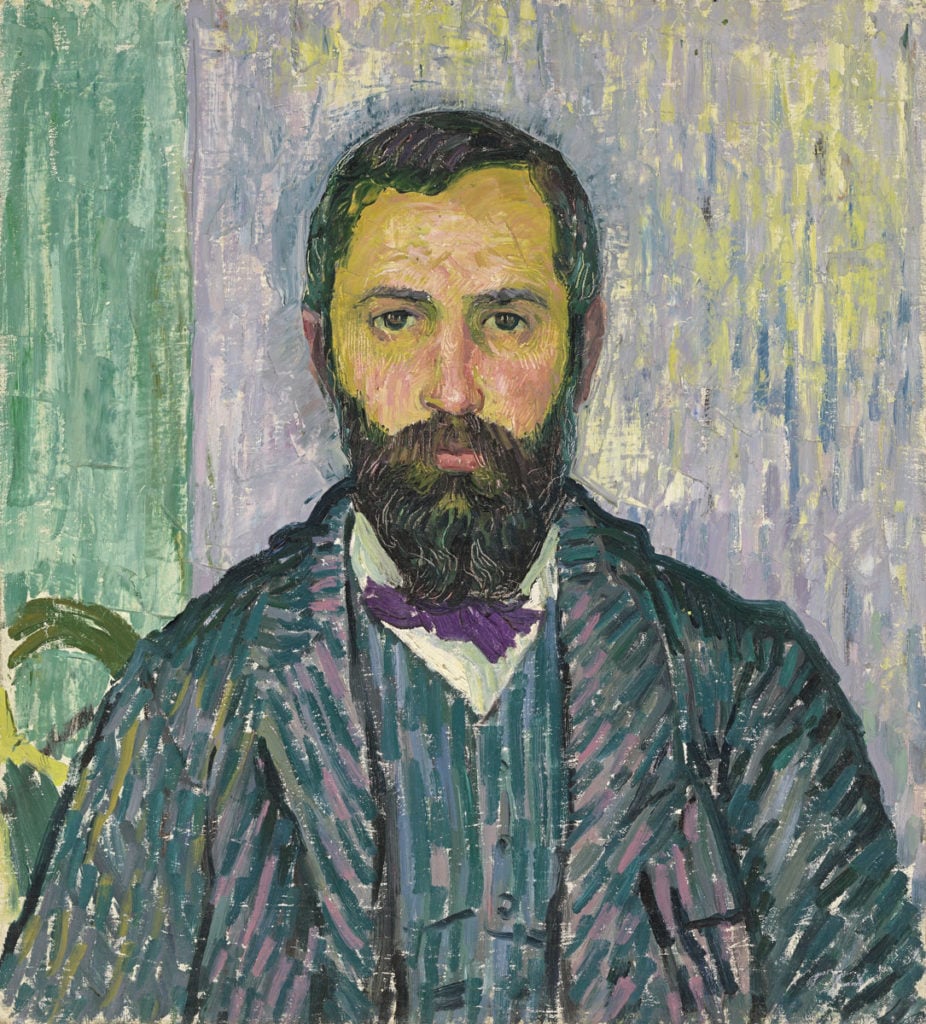

Cuno Amiet, Stilleben mit Zitronen (1908). © D. Thalmann, Aarau. Courtesy of bromer kunst.

In 1893, Amiet returned to Switzerland, where his new colorful style was not well received. (His first exhibition at the Kunsthalle Basel in 1894 garnered a great deal of criticism.) However, it was at this time that he met Ferdinand Hodler, another Swiss artist fighting against the tides of popular taste, whose work and interest in art nouveau would have a great influence on Amiet’s style.

Before the turn of the century, interest in Amiet’s work increased and he began to experience his first taste of commercial success. In 1898, after marrying, he moved to Oschwand, Switzerland, where his home became a hub for artists, academics, and writers.

By most measures, Amiet was a hugely successful artist during his lifetime, with exhibitions at the Guggenheim in New York, the Royal Academy of Arts in London, and at the Venice Biennale in 1934. He was also the only Swiss artist in “Die Brücke,” an influential group of mostly German expressionist artists founded by Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff.

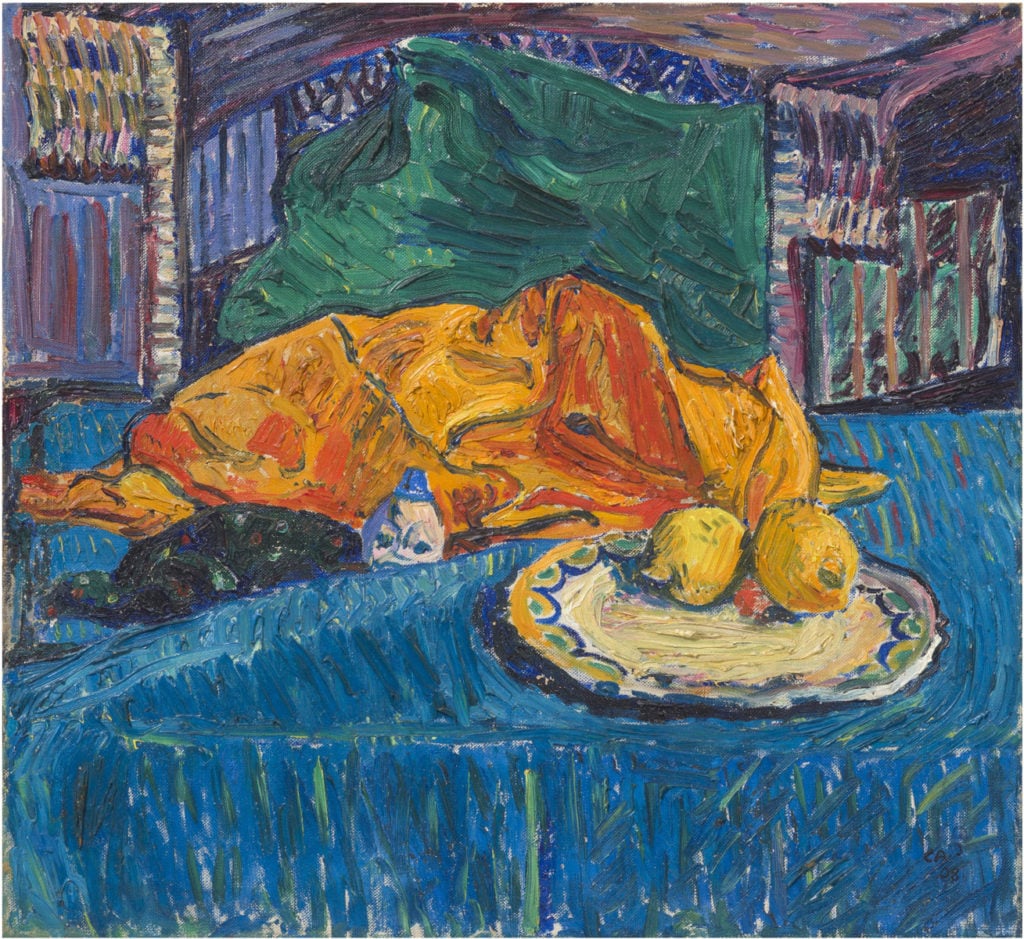

Installation view of “Cuno Amiet” at bromer kunst, 2018. Courtesy of bromer kunst.

Yet, outside of his home country, Amiet remains a lesser-known figure to the general population. According to Zaeh, that’s partly due to misconceptions about his work.

Amiet is often described as Post-Impressionist, but that’s not entirely correct. As the artist himself once said, “My nature is contradiction. Similarity is unfamiliar to me.”

“He didn`t stick to one artistic style or movement,” Zaeh says. “He painted works which could be ascribed to Pointillism, Symbolism, Cloisonnism, and Divisionism, to name only a few. He added his personal touch to every style he experimented with, and therefore helped to develop those movements further.”

Cuno Amiet, Winterlandschaft (rot) (1928). © D. Thalmann, Aarau. Courtesy of bromer kunst.

“Amiet is—from an international point of view—a hidden gem,” Zaeh says. “I’m confident that it is only a matter of time until museums and leading galleries outside Switzerland with a focus on modern art will rediscover his oeuvre. The quality of his work is simply too good, his role as a groundbreaking artist in art history speaks for itself.”

The market for Amiet’s work is quieter now than it has been in the past, especially over the last eight years, when his work sold for over a million several times. (His 1908 painting Winterlandschaft sold for $1,476,787 in 2010, setting the record for the artist.) He has a strong collector base across Europe, especially in Austria, Germany, France, and, of course, Switzerland. But Zaeh believes demand is going to grow soon too: “I‘m convinced that we’ll see higher amounts being paid for his works again, in both galleries and auctions,” he says. “From a market standpoint, it seems be a good time to purchase Amiet’s work.”

Installation view of “Cuno Amiet” at bromer kunst, 2018. Courtesy of bromer kunst.

“Cuno Amiet” is on view at bromer kunst in Roggwil, Switzerland through July 1, 2018.