‘I Look For Art That Is as Close to the Bone as Possible’: Pioneering Outsider Art Dealer Frank Maresca On How the Field Has Evolved

Artnet Gallery Network

Outsider art is a term that gets bandied about rather familiarly today as a catch-all for artists who have created outside the mainstream art world. Most of us could likely name an artist or two who falls into the category—Henry Darger and Bill Traylor spring to mind. But when dealer Frank Maresca co-founded New York’s Ricco/ Maresca gallery back in 1979—with a focus on the nascent collecting field—hardly anybody knew what that term meant.

More than 40 years have passed since he founded his gallery, and Frank Maresca says the field is still in its early days. “The whole field, if you want to call it that, of Vernacular–Self-Taught–Outsider is still really in its infancy when compared to contemporary and modern,” he said.

Maresca recently spoke with us about what’s changed in the field since he opened his gallery—and what’s just getting started.

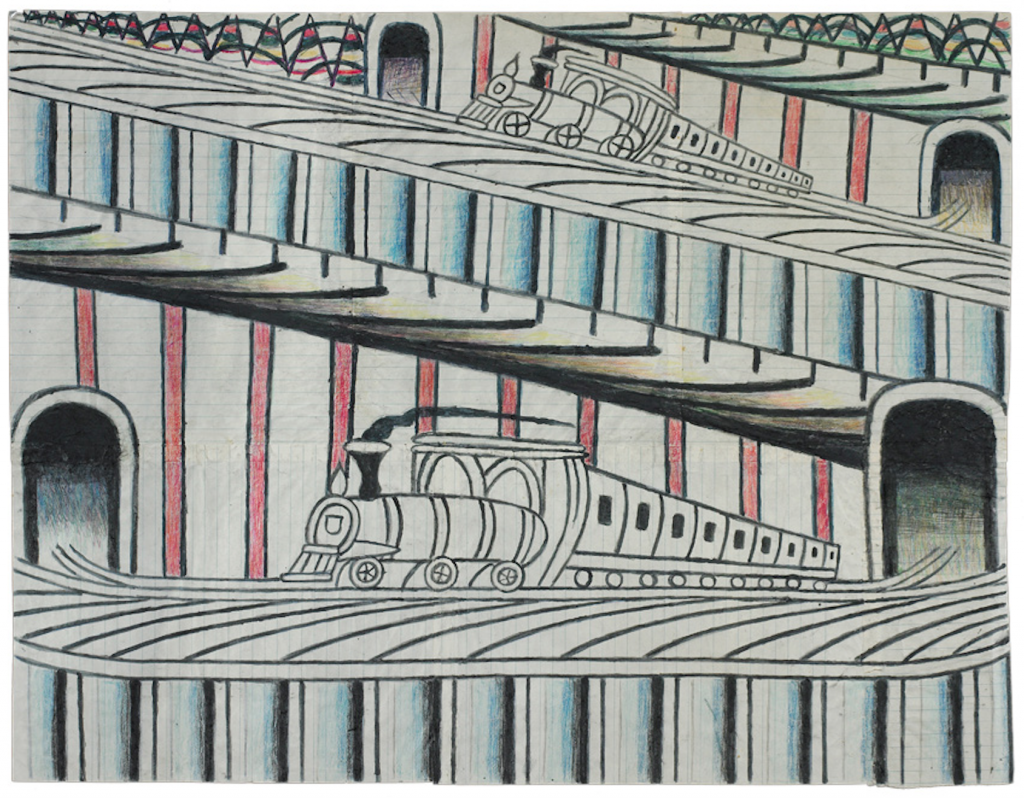

Martín Ramírez, Untitled (Trains on Inclined Tracks) (1960–63). Courtesy of Ricco/Maresca.

When you founded your gallery, Outsider art was not nearly as well known as it is today? How did you first become interested in the field?

I had an uncle who worked at the Brooklyn Museum and, as a child, I became aware of tribal art through his collecting interests. In 1976, the Brooklyn Museum had an exhibition titled “Folk Sculpture USA.” When I saw that show the objects brought me back to my many childhood visits; the works possessed the same raw, unadulterated power of great tribal art. I immediately became hooked. You could say that my early appreciation of tribal art led to folk art, which ultimately led to Outsider and self-taught art—as there’s a vein that runs through all of them.

How would you define “Outsider” art as opposed to self-taught, folk, and vernacular art?

Vernacular art is an umbrella term that is all encompassing, it simply means “of the people” or non-academic. Outsider art, as I define it, aligns with Jean Dubuffet’s definition of art brut, that is, art that is produced by people operating so far outside of society as we know it that they need the help of caregivers—this often means people who are institutionalized or hospitalized for one reason or another. Self-taught art is produced by individuals who do not operate within (and are for the most part unaware of) the art-historical tradition. Folk art predominantly comes out of learned popular traditions or apprenticeships like wood carving, quilting, and metalsmithing.

Are there any special moments of discovery that stick out in your mind?

Almost 40 years ago I was unaware of an artist by the name of Martín Ramírez. One day, I happened to be visiting Phyllis Kind’s gallery—at the time located on Greene Street in Soho—on the wall was a mesmerizing work depicting a very vertical train tunnel composed of hundreds of concentric arches. At the bottom of the six-by-18-inch work was a train emerging from the darkness. This work stopped me cold. I knew nothing about it, but it just grabbed a hold of me and immediately took me on a voyage. I asked Phyllis who the artist was and she proceeded to explain—but I think she was a little mystified that I did not know the work or the story behind it. Just like “Folk Sculpture USA” at the Brooklyn Museum, this was the second epiphany that led me to Outsider art. Certainly a personal discovery, all the more satisfying is the fact that for the last 13 years Ricco/Maresca has represented the Martín Ramírez estate exclusively.

Rosie Camanga, Untitled (1950–60). Courtesy of Ricco: Maresca.

Your current exhibition “Rosie Camanga: Flash!” brings together a series of tattoo designs by an artist from between 1950 and 1970. Can you tell me more about these designs and the artist?

Modern flash art (art that is produced by tattoo artists) goes back to the late 19th century. Tino (“Rosie”) Camanga moved to Honolulu from his native Philippines sometime prior to World War II, he became a tattoo apprentice in the mid-1940s and at one point opened his own shop. Rosie’s oeuvre was outside of the tattoo tradition, he created images that had never been seen before, a mix of popular iconography and his own visual idiosyncrasies. His designs, which were intended to be translated onto skin, transcend their original purpose and stand on their own as works of art.

In the words of Don Ed Hardy (one of America’s premier tattoo artists, who is also a collector and historian of flash): “[Rosie] segued from standardized versions of classic tattoo designs to eccentric and mysterious scenarios that were his alone. The format of a sheet of flash, crowded with multiple images, or the notion that something might be appealing to someone to wear indelibly for life, were mere jumping-off points for the world he created… The overall effect is a wacky mixture of cartoon humor, lofty emotions, menace, and smoldering sexuality.”

What are the joys of collecting Outsider art?

Art is, in the end, communication… It doesn’t matter which medium it uses. What I look for is something that I have not seen before. You could make the philosophical point that everything comes from somewhere, but I look for art that is as close to the bone as possible; art that owes little or nothing to what came before it. I want art to transport me to another place, sometimes it’s just for a minute, other times it could be life changing. Art should not be wallpaper.

Who are your collectors?

My collectors have changed over the years. In the beginning, putting museums aside, the majority of them were primarily interested in Folk and tribal art, work that tends to come out of a tradition. For the last 10 years, however, virtually all of the new collectors participating in the gallery have come out of contemporary and modern. It’s all about the concept of crossover; a dialogue occurring between vernacular and mainstream or academic art.

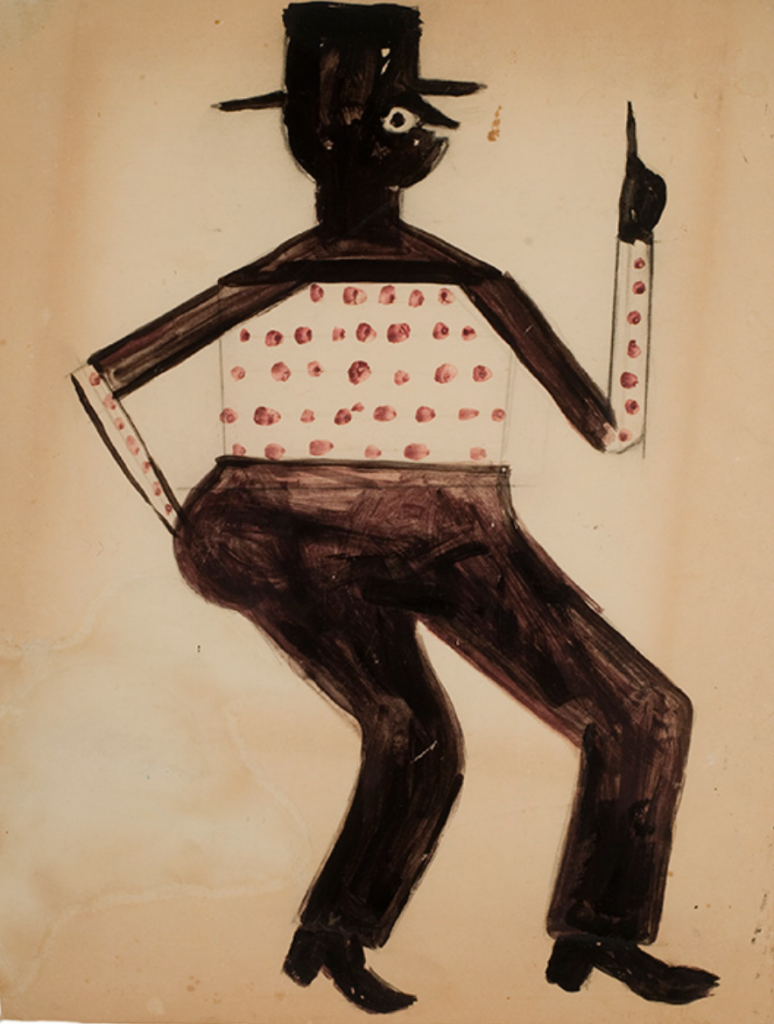

Bill Traylor, Man Pointing Up (c. 1939–42). Courtesy of Ricco Maresca.

Following up on that then, how has the market changed over the years since you first started as a dealer?

The market is a funny thing. Sadly, what something costs seem to be equated to a level of appreciation. It all speaks to the commodification of art and I suppose that will probably never change. Vernacular/Outsider/self-taught art has taken that same route, except for the fact that we are closer to the beginning of their monetary journey. Back in 1982, a work by Bill Traylor might have cost around $500, today that same work might be $50,000 (the auction record is above $500,000). A Henry Darger that might have been purchased at one point for $7,000 today might bring approximately the same price as the record for Traylor. Works by Edmondson are also in that same range.

What’s exciting in the field right now?

The field itself is exciting. Just a few months ago we participated in the ADAA Art Show with a one-person Martín Ramírez booth. Ricco/Maresca is one of the newest members of the ADAA and it was the first time that we exhibited at the fair. Aside from selling out a high percentage of the works on view to new collectors, at the end of the fair we were honored to learn that the membership voted us as one of the “Best in Show” gallery presentations. My strong guess is that that honor would have never happened as recently as five years ago.