Meet Hiroshi Senju, the Only Artist in Chelsea Right Now Who Uses a 1,000-Year-Old Japanese Technique (and Weasel-Hair Brushes)

Artnet Gallery Network

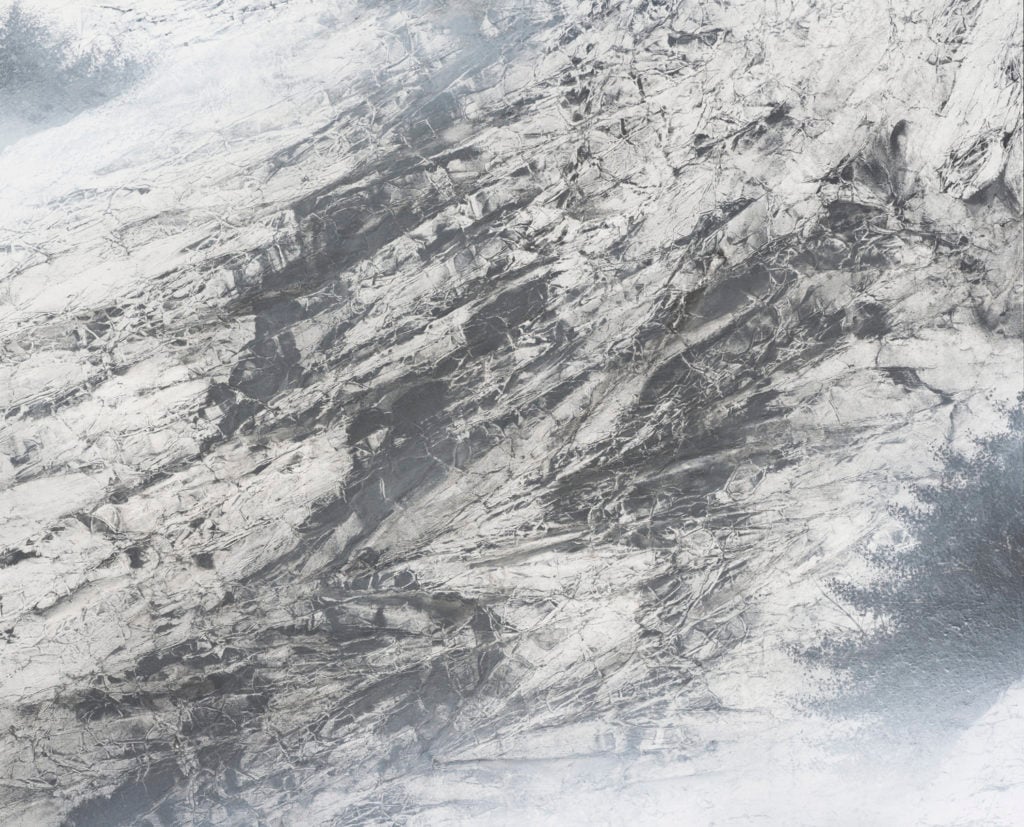

Hiroshi Senju’s new series of black-and-white cliff paintings, on view now in his exhibition “At World’s End” at Sundaram Tagore’s Chelsea location, are intricately detailed in appearance. But they’re not nearly as intricate as the process behind them.

Senju is perhaps best known for his large paintings of waterfalls, a subject he explored almost exclusively for years. A decade ago he took a different aspect of Mother Nature as his muse: the cliff.

Hiroshi Senju, At World’s End #17 (2017). Acrylic and natural pigments on Japanese mulberry paper mounted on board, 25 11/16 x 31 5/8 inches. Courtesy of Sundaram Tagore Gallery. ©Hiroshi Senju.

While his subjects may be universal, his methods are not. Senju is one of the only artists in the world today who works in the Japanese tradition of nihonga, a storied thousand-year-old style of painting.

The word nihonga was coined in the late 1800s by the American philosopher Ernest Francisco Fenolllosa, who used it as a way of labeling the formal characteristics of a traditional Japanese painting style that incorporates materials sourced from nature—everything from mineral pigments and animal-hide glue to ground shells and stones used to make paint. However, the methods and materials identified by Fenolllosa, including the painstaking technique employed to fuse its elements, have roots that date back to as early as the 8th century.

Senju’s process and commitment to nihonga are as exacting as his imagery. His tools are highly specialized and made by hand from natural materials such as weasel hair and raccoon bristles. He paints on surfaces made from washi (a tough, fibrous paper) and the bark of Mulberry tree that can only be sourced in winter; the material itself can only be crafted by a master paper-maker in Japan. He hand-screens the paper himself, often discarding many pieces along the way in pursuit of finding flawless sheets.

That’s actually how his interest in cliffs came about: Senju noticed that the wrinkles of these discarded pieces of paper mimicked the surface of a rock face. He began experimenting with folding, crushing, and crinkling the substrate, then pouring pigment onto it and further altering it with his brush. He made his first cliff painting in 2007, and hasn’t stopped since.

Hiroshi Senju, At World’s End #19 (2017). Acrylic and natural pigments on Japanese mulberry paper mounted on board, 51 5/16 x 63 13/16 inches. Courtesy of Sundaram Tagore Gallery. ©Hiroshi Senju.

Senju is now a decade into his exploration of the cliff. His formal experiments, combined with his mastery of Nihonga techniques, compliment the subject matter. Up close they appear dirty; from a distance, they look grand.

“At World’s End” marks the culmination of big year in North America for the artist. In May, Senju was presented the Isamu Noguchi Award, an annual prize given by New York’s Noguchi Museum to artists who embody the eponymous sculptor’s “spirit of innovation, global consciousness, and commitment to East/West cultural exchange.” His six-panel piece, “Shrine of the Water God (Suijingū)” was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art last year and put on display in the museum’s Japanese gallery this spring. Currently, his work is also included in the exhibition “Atmosphere in Japanese Painting,” on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

“At World’s End” is on view at Sundaram Tagore through December 9, 2017.