Has the Impressionist and Modern Market Lost its Luster?

Artnet Price Database Team

The past few years have brought whispers that the Impressionist and Modern sales are losing steam. In the 1980s, black-tie sale rooms at Christie’s and Sotheby’s attracted heated bidding from collectors looking to invest in sure-bet works. Today, these evening sales are decidedly less well-healed and can border on tepid— it’s not uncommon for lots by big names to go unsold.

As the November auctions approach, we decided to take a peek behind the curtain and see what’s really going on in this juggernaut market.

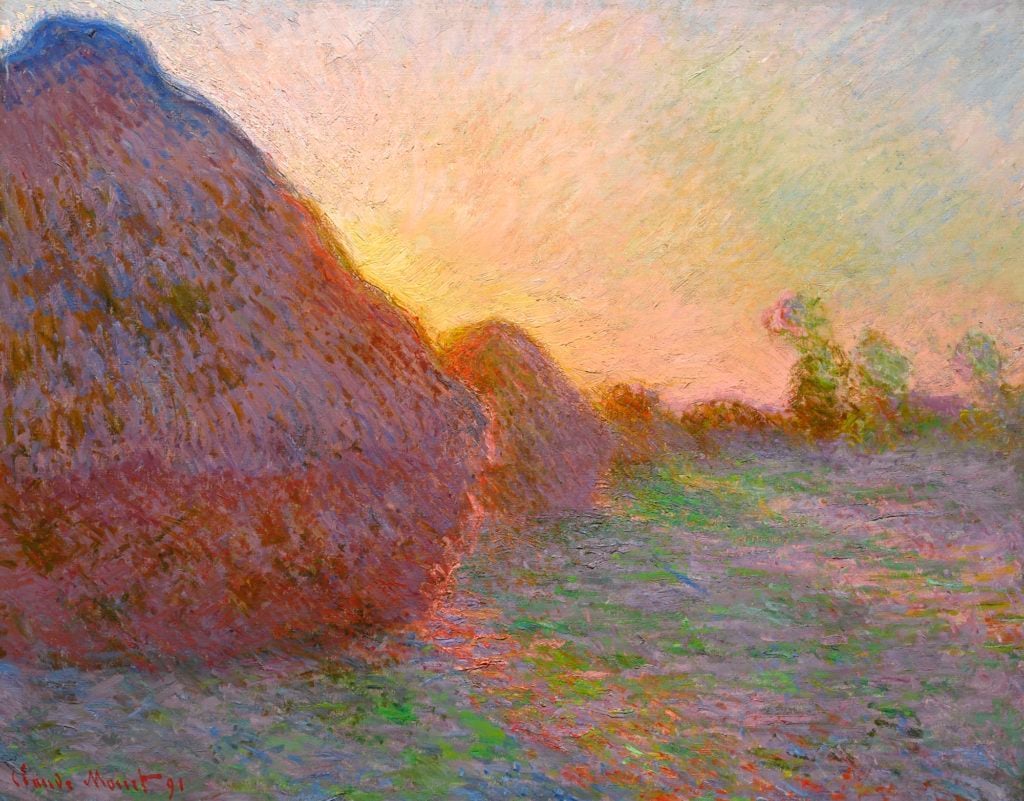

The Impressionist and Modern market is no longer what it once was — there’s no denying it. The past few years have seen markedly declining enthusiasm, and at recent auctions works have sold at their low estimate. Regardless, sale totals have soared, but driven only by a handful of top lots. According to the Artnet Price Database, during Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern evening sale this past May, despite a star Claude Monet selling for $111 million, nearly half of all lots sold below estimate. At the Christie’s London evening sale in June, only two works even carried high estimates over $12.6 million—and neither found a buyer.

Both galleries and auction houses are struggling to adjust to changing tastes. Just last month, longtime New York dealer Francis Naumann announced he was closing after nearly 20 years in business. “There are fewer and fewer collectors of 20th-century art because the younger generation wishes to identify with the art of their times and feel that the art of the past is—by definition—passé,” Naumann told Artnet News.

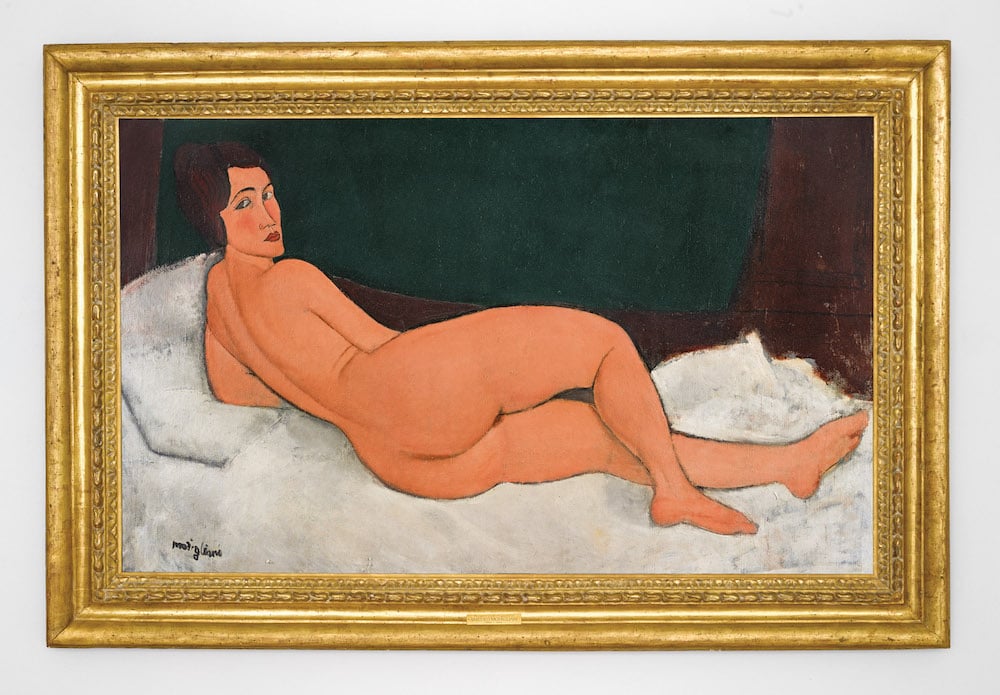

Amedeo Modigliani’s Nu couché (sur le côté gauche) (1917) sold for $157 million at auction last spring. Courtesy Sotheby’s.

There’s only so much good Monet to go around. The farther we move from the time when these works were made, there are fewer museum-quality Impressionist and Modern works left in the market that have not been claimed by institutions and collectors.

While traditional economic wisdom holds that scarcity should make the remaining works more valuable, the truth is that many of these remaining works left on the market are often simply less appealing. The rare exceptional work will still achieve sky-high prices—like the aforementioned gorgeous Monet haystacks, or an exquisite Amedeo Modigliani nude—but collectors are less likely to shell out top-shelf prices for second-tier work, especially when they can grab great Postwar and contemporary works for less.

Another possible reason for the lag? A collapse of the traditional hierarchy of the art historical canon. For years, European Modernism reigned supreme. But a shift toward a global narrative has definitely changed the conversation—and the market.

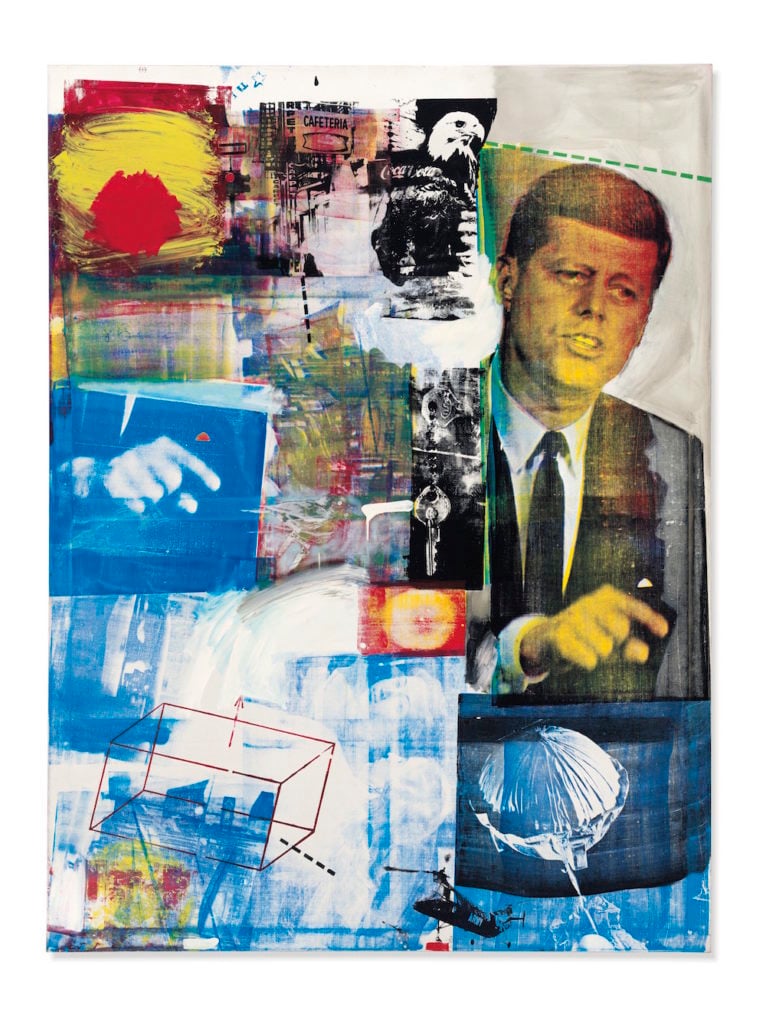

Robert Rauschenberg, Buffalo II (1964). The painting sold for $88.8 million at auction earlier this year. Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Postwar and contemporary offerings are increasingly becoming the blockbusters of the auction season, with works by Mark Rothko, Jean-Michel Basquiat, David Hockney, and Robert Rauschenberg pulling in eight-figure hammer prices.

If we compare data from the Price Database for January to October in 2019 to the same period in previous years, a pattern emerges: In 2019, six of the top ten top lots from the top auction houses were from postwar and contemporary artists. What’s more, two of the top three lots of the year went to Jeff Koons and Robert Rauschenberg—making this the first year ever that Impressionist did not have a solid hold on the top three lots at the major auction houses. If you look at the same period in 1999, all ten of the top lots at that point in the year were within the Impressionist and Modern category, and only one in the top 20 was Postwar.

All of this is not to say that Impressionist and Modern is no longer a major force—Monet is unlikely to ever be a bad investment, and sales at Christie’s and Sotheby’s are still comfortably bringing in over $100 million per-go around. Still, it’s worth keeping a close eye on the November blockbusters, and noting that other categories are now considered just as safe (or even safer) of a bet.

To learn more, commission your own Artnet Analytics Report.