Why the Times Square of Yesteryear Is Still Inspiring Jane Dickson, One of New York’s Great Painters of Nightlife

Katie White

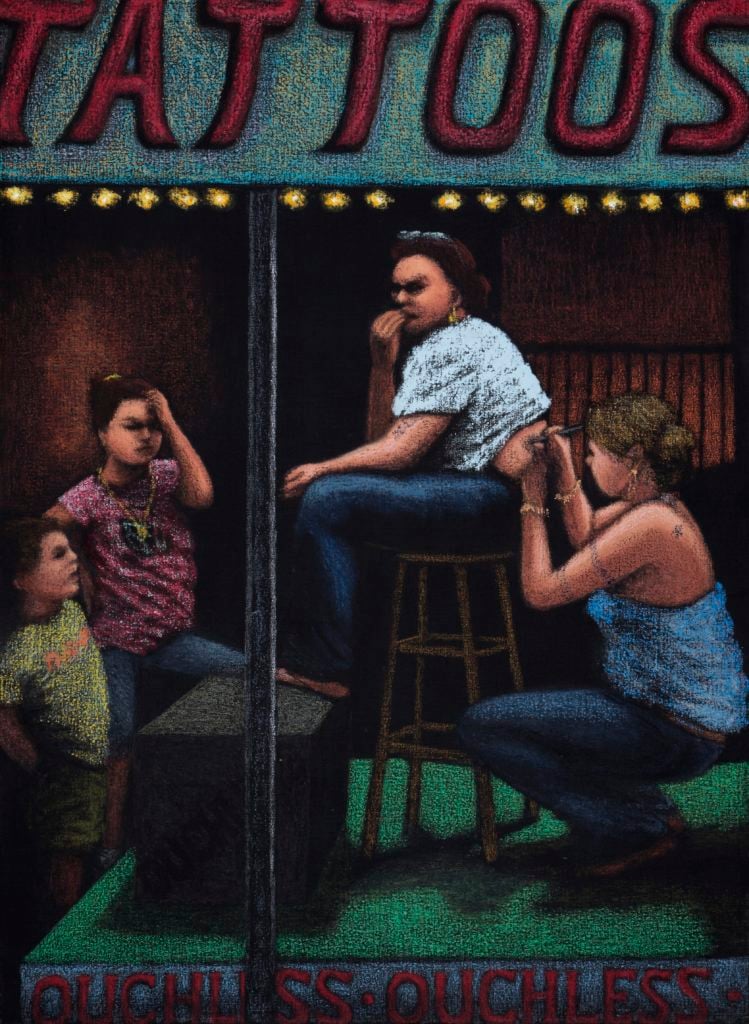

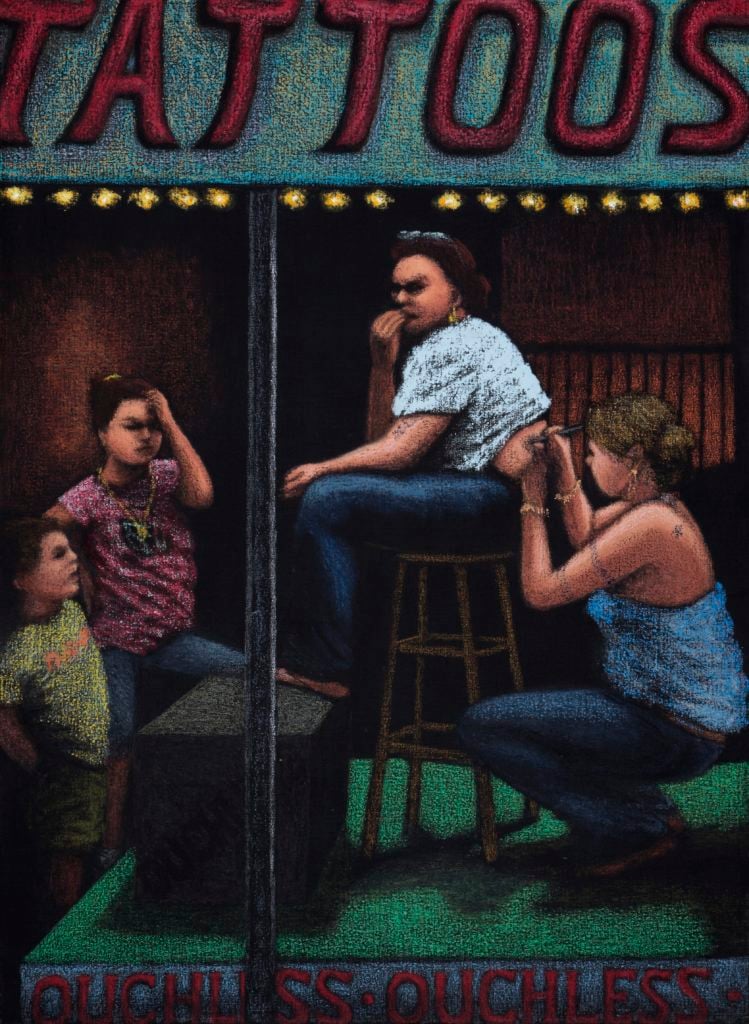

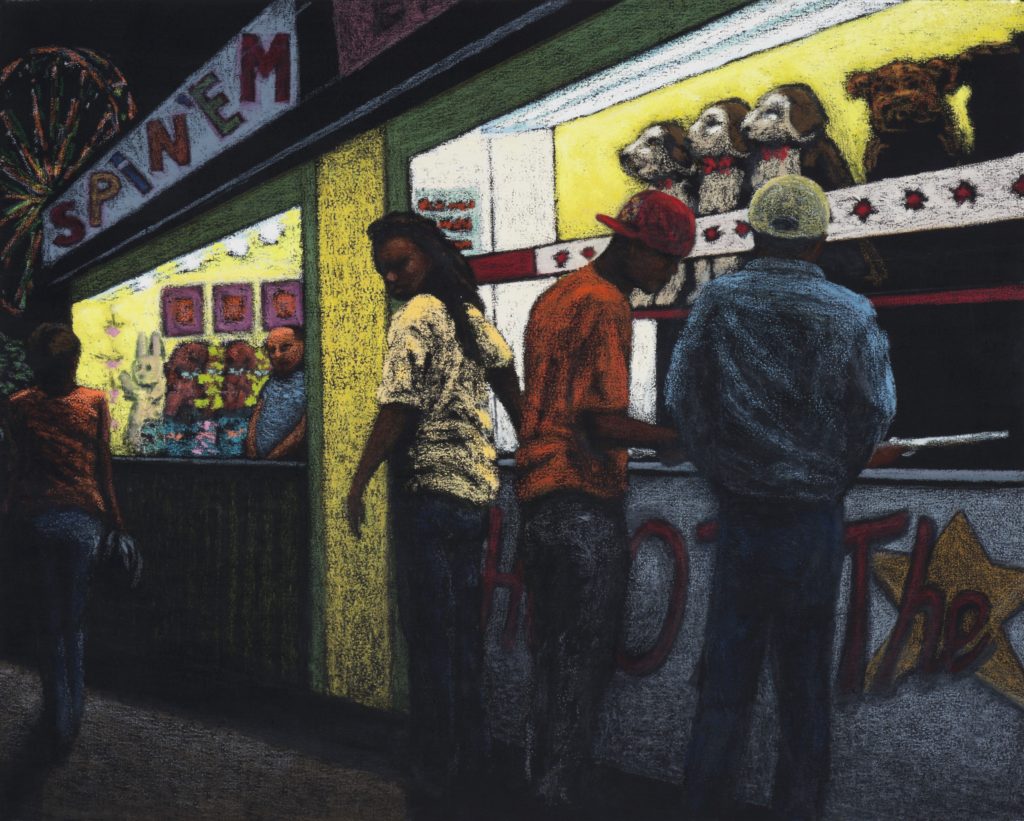

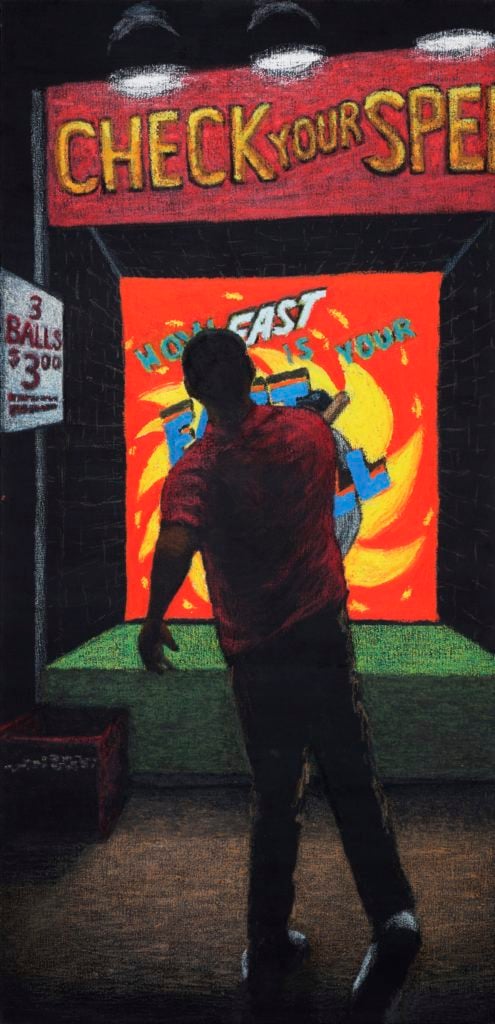

Jane Dickson’s world is one that comes to life when the rest of us are fast asleep—a nighttime mix of tawdry carnival booths and tattoo parlors, darkened highways and casino gamblers.

A Chicagoan by birth, Dickson has been a steady fixture on the New York art scene for over a generation. Arriving in New York in the late 1970s, she moved to Times Square, a place she would live, work, and raise children for decades, and found herself drawn to the seedier aspects of the world outside her window. Over the years she has cultivated a singular style—think Weegee meets Edward Hopper, with a dash of Seurat—that was often at odds with prevailing tastes.

But Dickson has never been an outlier—far from it. During the 1980s and ‘90s she was at the core of a kaleidoscopic city-wide arts scene that included graffiti artists, fashion designers, and filmmakers with Dickson acting as an important link between the street scene and the traditional art world through numerous collaborations. Her installation City Maze, at the famed Bronx art space Fashion Moda entailed a large maze built of cardboard boxes and was tagged by graffiti artists like Crash and NOC 167. Meanwhile, Dickson’s husband, the filmmaker Charlie Ahearn, was the director behind the iconic hip-hop centric film Wild Style (1982).

Jane Dickson, 2019.

Now Dickson’s career is getting a closer look in the New York edition of “Beyond the Streets,” a Los Angeles-born exhibition that repositions the genesis of street art and its influence within a larger cultural narrative.

We recently caught up with Dickson to talk about her the Times Square of yore and why it’s still on her mind.

Jane Dickson, Shoot the Stars (2005). Courtesy of the artist.

When I think of your work, I think of Times Square first and foremost. What years did you live there and how did you wind up there in the first place?

We moved out at the end of 1992, but my studio was there until 2008. So from 1978 to 2008 I was working or living there. My new book, Jane Dickson in Times Square (2018), is full of my photos from the time and gives some idea of what it was like.

How I wound up there is basically that I had studied animation. I saw an ad in the New York Times that said, “Animators wanted. Willing to learn computers.” The job was for the first digital light board in Times Square, at 1 Times Square where they drop the ball. In those days they needed someone behind the board all the time because of glitches. First they had tried to train computer programmers to make art, but they couldn’t so they thought they’d try the opposite and train me.

I decided to work the night shift on weekends to keep time free for my studio practice. That was my logic at the time. But what I saw going on in the street at night was amazing. It was scary, but interesting. I would get to work at 4 p.m. and I’d talk to the sales people and they’d tell me what they needed me to do then they’d all leave about 5:30. Working from 4 p.m to 12 a.m. seemed perfect for me, to be uninterrupted and alone. I would go out for my lunch break which was really dinner and get something at the deli which was always full of extremely stylish transvestites starting out their evenings. It was party time then, pre-AIDS. My boyfriend would pick me up at the sign when it closed and go to Studio 54, or wherever was the spot of the night. That job wasn’t interrupting my day life or my night life as far as I was concerned.

Installation view of works by Jane Dickson in “Beyond the Streets,” 2019.

What was it like to be a figurative painter in those years? Who were you looking at?

I was from Chicago so I was very interested in the Chicago Imagists, the Hairy Who. My parents divorced and my mother moved to Paris when I was in high school. I would visit her in the summer and I studied at the Beaux-Arts there. When I was 18 I moved to Paris for a year. I had a difficult relationship with my mother and I felt I needed time to try to work that out. This was 1970, two years after ‘68 student Manifestation. No one in the art scene there understood what I was doing. Painting was dead, as far as they were concerned—”We did painting really, really well and now we’re done with it” was the feeling. So there was huge resistance to what I was doing. But I would look out at situations and into the world and think that if I could capture that I could show it to my mother or father and they could understand me.

I tried to be abstract. I read about it, learned about it. But I’m a plainspoken Midwesterner on some really profound level and my abstract painting went the way of my high school poetry. it just seemed like bullshit. When I was in Paris I realized that I was just American. I was not French and I would never be accepted, even if I lived there for 50 years. I thought, I want to go home and embrace that, embrace being American. I loved Watteau, Degas, Seurat, but then I wanted to look to my American forebears, from Sargent to Hopper to O’Keeffe to Ed Ruscha.

Jane Dickson, Check Your Speed 3 Balls (2005). Courtesy of the artist.

But your material choices can be pretty unusual.

There is a strong strain of figuration that can be excruciatingly retro, that wants to like return to Caravaggio. I needed to be representational but I don’t want the good old days when men were men and paintings were paintings.

It was the punk era and painting was dead. I crept my way into painting from animation. I started painting on crappy materials. You don’t have to go to the art store to buy art supplies was the ethos. I liked using materials that were culturally devalued. I wanted to match the subject matter to the materials. For a series of portraits of strippers I worked on sand paper because that made sense to me: look but don’t touch. The oil stick is seductive but the material is rough. I did paintings of houses on carpet samples. Highways on astroturf. It’s simulacrum. I also chose materials that weren’t traditional to keep from getting too fluent. I like the struggle: How do you get the effect of smoke on astro turf? I like those problems.

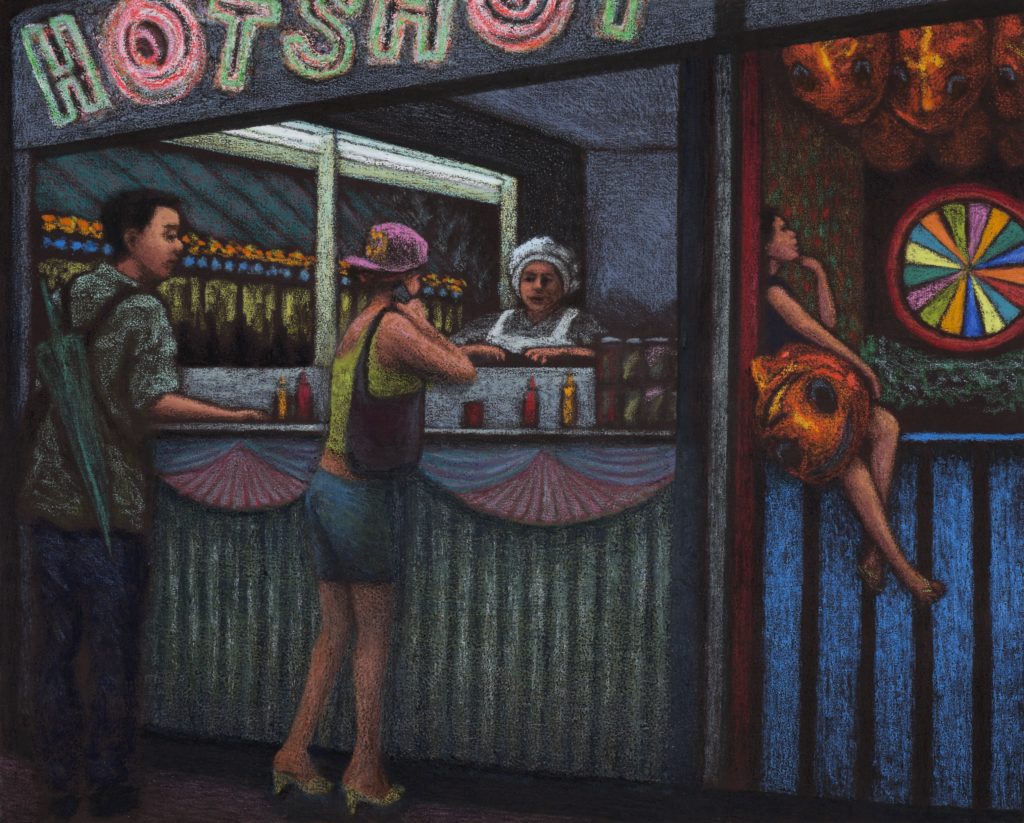

Jane Dickson, Hot Shot (2005-2016). Courtesy of the artist.

But you were involved in a lot of different projects with a bunch of artists who were working in all sorts of styles, like graffiti and conceptual art. You were part of the artist group Colab along with your husband. And you curated “Messages to the People” with the Public Art Fund, a billboard in Times Square where artists presented 30-second animations, once an hour.

I was so delighted to meet artists of all stripes. Yes, I was Colab with James Nares, Kiki Smith, Joe Lewis, Walter Robinson… We organized the “Times Square Show” in an empty massage parlor in 1980. That show had everybody: Jenny Holzer, Keith Haring, Fab 5 Freddy. David Hammons and I met there. For “Messages to the Public” I thought I will make this happen with my boss if I get to pick the artists. I had so many talented friends. I picked Keith Haring for his first public show. I had seen his work in the “Times Square Show” too. I was really excited by that moment, everyone was mixed up together. And the street artists, they were incredible. It was like they were storming the gates. Most hadn’t gone to college. They had incredible energy and determination and I loved working with them. I had collaborated with Crash when he was 17 at Fashion Moda for City Maze, a maze from cardboard that I built in the storefront. The kids in the neighborhood went crazy for this maze. They loved the maze to pieces.

I know you’re working on a second book and soon your archive will be heading to Cornell University as part of its “Downtown Archive.” But what are you painting now? Times Square has changed a lot.

With the new book, I’ve actually been readdressing the 1980s. I’m 67 now and I’m at a place where I can look back at the arc of my work. There are all these places where I had a baby, an operation, a sick relative. There were interruptions. A spiral rather than a straight line. Things I meant to paint but didn’t, and I just think, “Why not? I’ll do it now.”

I’m not trying to make these paintings look like they’re from that earlier period. You’d never confuse them. I’m working in acrylic now and I don’t really know how to do it. But there’s also the sense that I’m looking at a subject in hindsight. At the time that was what I was looking at out the window. It was my present. Now its my past. How does that look from here?

More specifically, I have all these photographs of wigs shops that I am feeling an urgent need to paint. Maybe it’s the Trump Era, this idea that I’ll have a blonde tonight or I’ll go crazy and have a redhead. I’m working on synthetic felt at the moment.

With the book I finally have to organize my photographs. I’d always thought of them personal reference material, they weren’t meant to be artistic or even in focus. I couldn’t very well set up an easel in Times Square. It was more shoot from the hip and grab what you can, but looking at them brings new things to mind even now.

“Beyond the Streets” is on view through September 29, 2019.