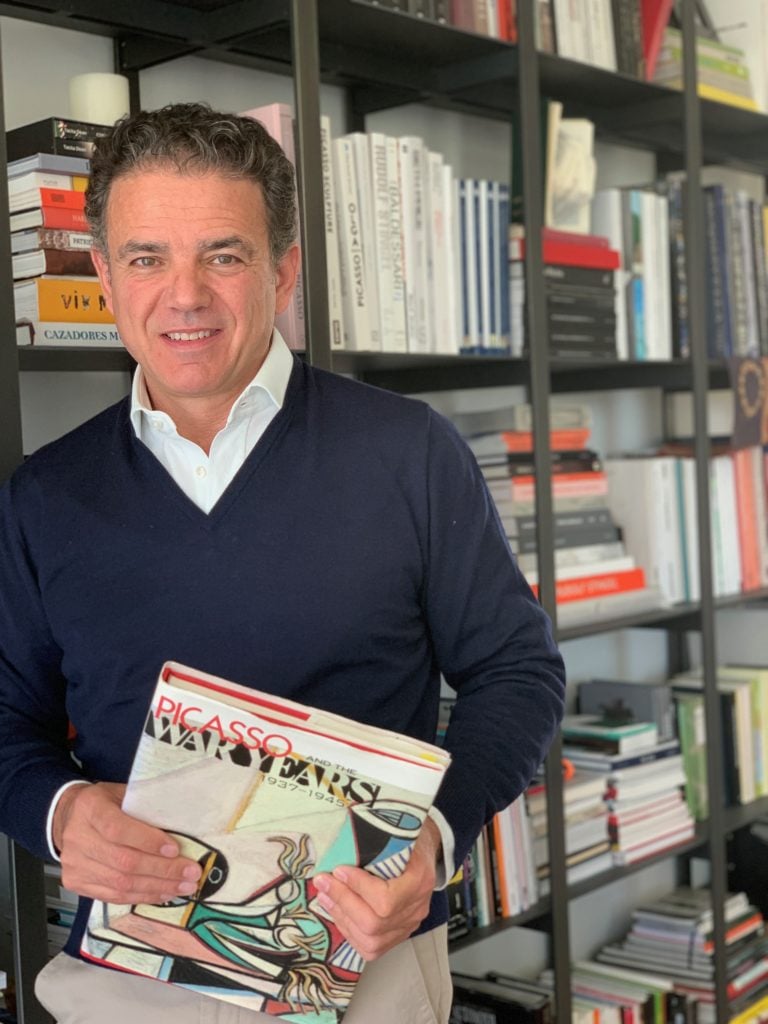

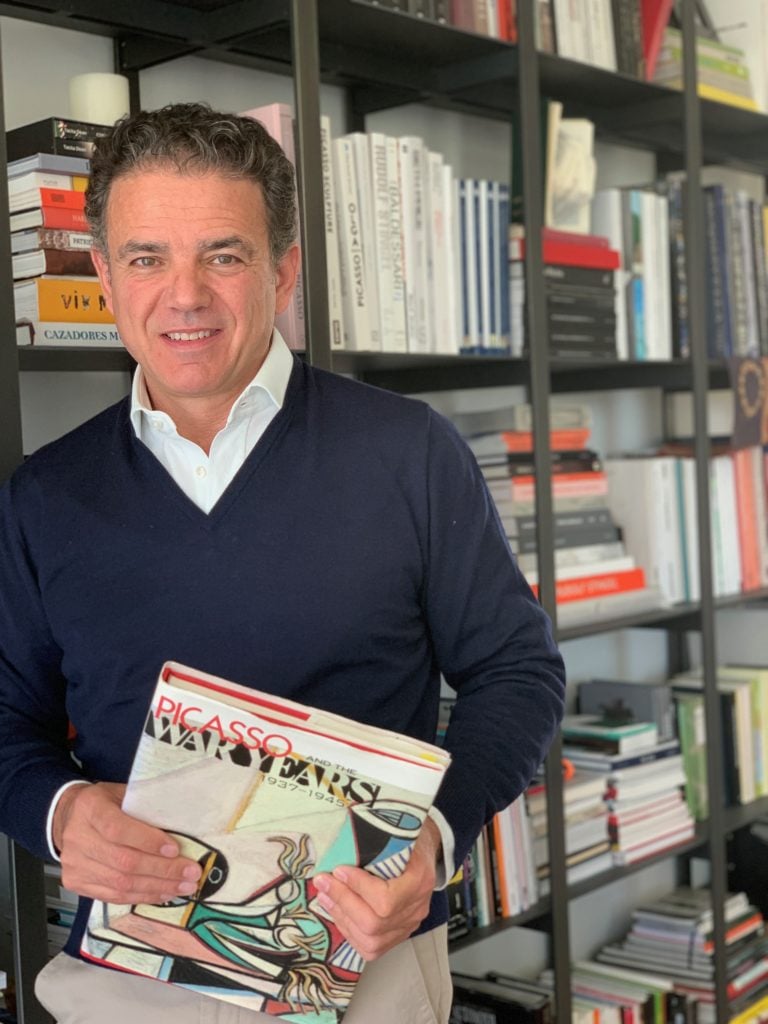

Collector and Entrepreneur Javier Lumbreras on the Ethics of Collecting Art and the Problem With Museum Boards

Artnet Gallery Network

Spanish collector and entrepreneur Javier Lumbreras has strong feelings about the ethics of the art market. His company, Artemundi, which he founded in 1989, is an international fund manager that uses art as an alternative asset, focusing on established artists of past generations. (What Lumbreras does not want is to tamper with the careers of young artists.)

Lumbreras and his wife Lorena’s personal art collection—called the Adrastus Collection—is focused on contempory artists who have strong social messages. Currently, the couple is renovating the Jesuit School of Arévalo, a sprawling medieval structure in Ávila, Spain, to serve as a private museum for their collection.

Recently, we caught up with Lumbreras who offered insights into the changes he wants to see on museum boards, and why contemporary art is sometimes a leap of faith.

In supporting culture, is it more important where the money is coming from or where it is going to?

That’s quite an important topic today. We’ve seen so many people on and off of boards who have been questioned in terms of either personal morality or the moral repercussions of their businesses. I support the idea that money has to come not only from legal sources but also from ethical sources. Countries have made a moral mistake by making the sale of arms legal, in my opinion. Museums are associated with higher values, common to all human beings—so I believe that museums need to have the right people in the right places and do a very thorough self-examination.

Where have you had the best experiences in your work with museums? What have you learned from those experiences?

I am on a couple of museum boards myself in New York. I am on the acquisitions committee and the curatorial committee at El Museo del Barrio, which has been a very rewarding experience because it’s one where you’re not only in participating with the museum purely through funds, but you also dedicating your time and your knowledge to the museum’s mission, to the Bronx and the Latinx community. I feel like it’s important that these roles come with a commitment of time, and you don’t just give money or loan the name. You need to really want to contribute to a community that you’re supporting and embracing.

What are the differences in your experiences between European and American museum boards?

If you’re thinking about this spectrum, there is the European cultural finance model on one end, the American on the other, and the UK somewhere in between. In Europe, culture is financed by the state, and in the United States, culture, as we well know because of the current crisis, is financed. There’s not a ministry of culture that supports these institutions, so there are tax rules that encourage people to donate.

Instead, we have a model based on the Rockefellers, the Melons, the Carnegies, who built the great libraries and museums, and that model is now struggling. What’s happening is that galleries are also becoming very, very powerful, with a few galleries concentrating a lot of power. Top-tier galleries can approach a collector and say, “you should be on a board,” and the gallery will basically propose you to a museum or through their contacts to be part of that museum board. That becomes a way for that gallery to have an influence in the museum.

When you come into a board holding the hand of a gallery, there is a stable of artists they are supporting, and maybe those artists that are not the best artists, maybe they’re second tier. Maybe they have very good qualities, but are not quite there yet. Well, in that case, these artists are going to make it and have exhibitions at some of the most important museums in the United States. And that truly bothers me, really kicks the hell out of me, because we’re using money to influence the museum process and artistic process in a very tightly knit way.

What effect do you think this relationship has?

Sometimes I have collectors that come to me and they say, “listen, who is the next great artist? Can you tell me who it is?” Some of these collectors have a lot of influence; they find an artist and they make them a star in a few months. They can master this scheme, but in the end, I don’t think it works. I think there’s a great dissociation between what the very rich buy—which is more decorative, more figurative, on typical canvas—and what institutions and true collectors tend to buy, which is very inspiring, intellectually enriching, and culturally meaningful, with content, message, and meaning.

I don’t put these kinds of works in the same categories because one is made to sell. Nowadays, galleries are becoming very conformist and they’re feeding their clients exactly what they want. Then they’re getting museum boards to follow up with these same artists. I had the director of an important museum tell me, “We don’t depend on wealthy donors yet and thank goodness.” Meaning: we get money from the state and have a yearly allowance. We can always pay our salaries. We don’t have to fire anybody. Every one of our employees is unionized. They don’t need to work for pennies.

Roman Ondak, Only Good News. Courtesy of the artist.

Tell me about your personal collection, which contains emerging artists as opposed to more established artists.

Our collection is not one that just happened, but one my wife and I built with absolute purpose. It was an intellectual discussion and we decided that we wanted to collect something that will contribute to society. The collection is exclusively young and emerging artists, whereas the investments I make with Artemundi never deal with living artists. I like art from the Renaissance to the most radical of today’s expressions as far as my mind allows me to go. Sometimes, with contemporary art, I have to make a jump. If I was in my 20s, it would be so much easier to understand it, so some of the contemporary artists we collect, I say to my wife, “This is another leap of faith.”

I don’t believe in private museums to the extent that they can become mausoleums, which is why we want to involve the public. I really value my friendship with Phillip de Montebello, and I consider him my mentor in many ways. He makes an effort to understand contemporary art and he’s excellent in the sense that he can adapt to that. I’m not sure I will be able to do that, but I’m trying!

Can you tell me more about your work investing in art?

I don’t struggle, morally speaking, when it comes to investing in art for Artemundi. It’s a term no one likes, but it’s becoming very mainstream. We just try to do it very ethically, in that we deal with artists that are already established and with works and periods that are clearly defined and studied.

We expressly reject using emerging art for investment since we don’t want to manipulate artists’ careers. It destroys them when you take an artist that is worth, say, 10,000, then you bring it to 100,000. There are steps that are missing from their career—an institution won’t be able to buy a work at $500,000.

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights. Courtesy of Museo Nacional del Prado.

What’s the best advice you have to give?

The best advice I could give would be that the purpose of life is not to be happy. The purpose of life is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to be tolerant, to know that you have made a difference for those in need.

The other one I like to say all the time is, the race is long, but in the end is only with yourself. I think that those two ideas really mark my life.

If you could own any work of art in the world what would it be?

Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights could fascinate me forever.

What about if you had to live in an artwork, which would you choose then?

There’s this work by Roman Ondak, a contemporary artist from Slovakia. He has an artwork called Only Good News. It’s almost like a medicine cabinet with glass doors and you can see through those doors inside. It’s got tons of newspapers piled up and there’s no room for anything else. We can think this is filled with “only good news,” and that’s where I would like to live.