Gallerist Jayne H. Baum on the State of the Contemporary Photography Market Today

Taylor Dafoe

Few art dealers have consistently had their finger on the pulse of contemporary photography the way Jayne H. Baum has for the last three-and-a-half decades.

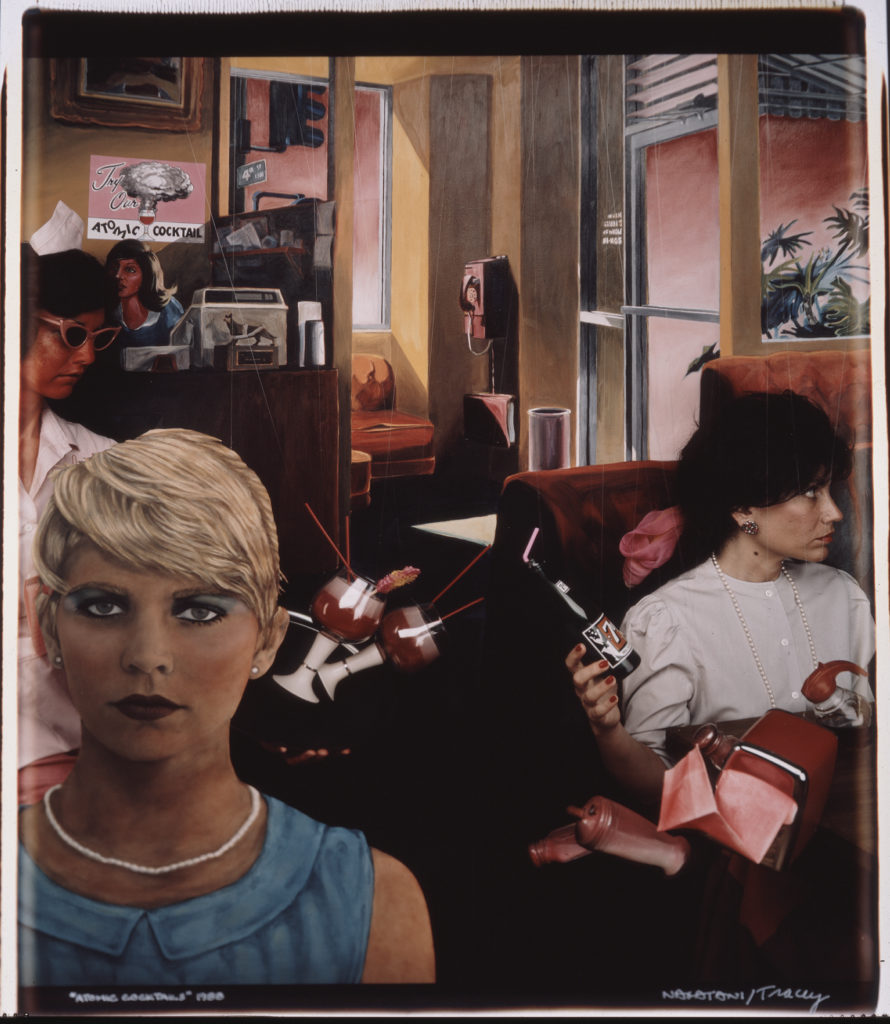

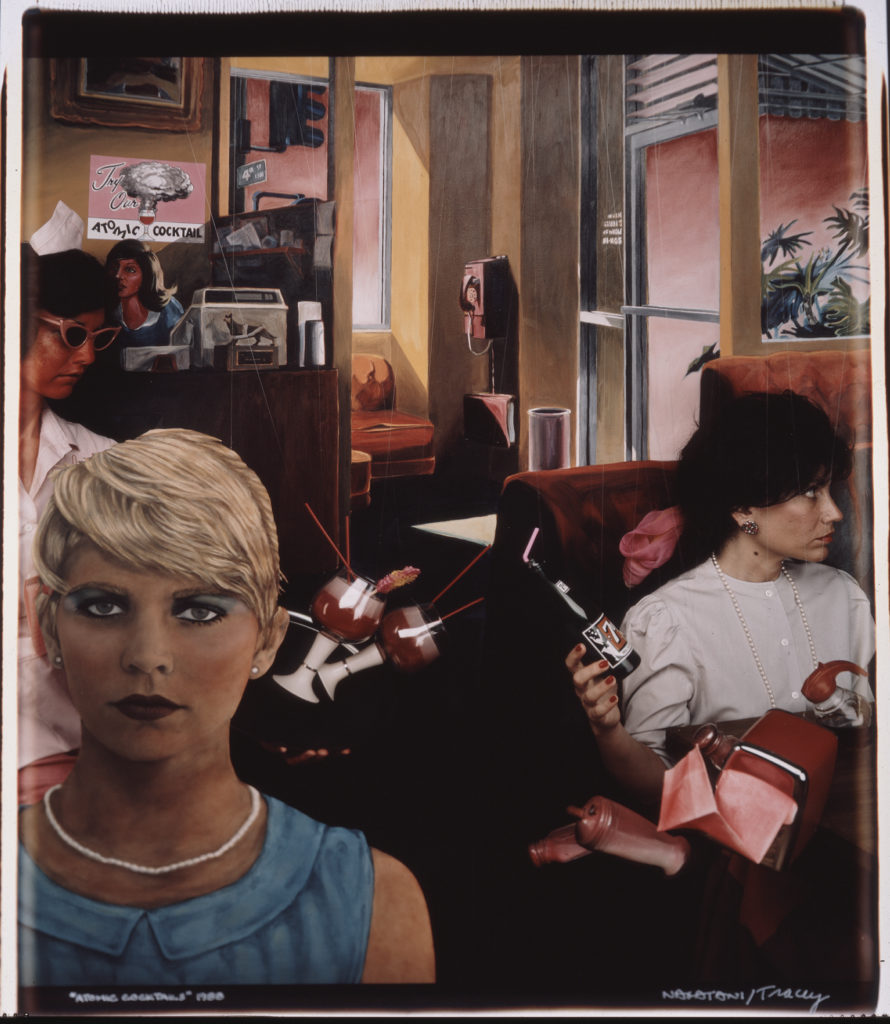

Baum founded her gallery, JHB, in 1982, opening a small spot in Midtown before moving to a larger location in Tribeca two years later. She made her name representing artists at the forefront of photography. Many of her artists, such as Patrick Nagatani and Nancy Burson, were grappling with issues and themes central to the discourse around the medium at that time—materiality, digital imagery, performance, and privacy.

After relocating to an even bigger space in Soho in ’88, Baum closed those doors for good in ’95, opting to move away from the brick-and-mortar gallery model altogether. In the name of working on a more private, personalized level, she scaled back business and began operating the gallery out of her apartment.

Baum has continued working there since then, occasionally mounting exhibitions, collaborating with institutions, and taking on consulting work. In preparation for AIPAD this week, she spoke with artnet News about what she’s bringing to the fair, her history as a gallerist, and the plight of photography dealers today.

Curator Jayne H. Baum. Photo: © 2018 Patrick McMullan Company, Inc.

Can you tell me about you’re bringing to AIPAD this year?

The overarching theme is “Serial Structures: The Object in Performance.” It’s a selection of nine artists and one duo who examine concepts of seriality, movement, and material in their work. Many of them, including Ellen Carey, Simone Douglas, and Amanda Means, use photographic processes to make unique objects. They also represent many different approaches to the medium—camera-less photography, Polaroid, and photograms, to name a few.

As much as all galleries today are struggling in the face of globalized business and increasingly digitalized content, I wonder if galleries specializing in photography might be having an even tougher time given the nature of the how we look at, buy, and sell pictures. Do you find that to be the case?

JHB Gallery represents artists who work across all creative mediums, including photography. Since the early 1980s, we acknowledged the importance of supporting artists working within the photographic discourse and new media, and as a result, we became known for pioneering new developments and ideas in this medium. Artists like Patrick Nagatani and Andrée Tracey, Nancy Burson, Ellen Carey, Alain Fleischer, Amanda Means, and Yuki Onodera—to name a few—all represent this.

The virtual/digital platform has certainly provided a new way of interacting and engaging with artworks, which also includes photography. But generally, in terms of today’s market, I find that there is not a huge difference between photography and other mediums.

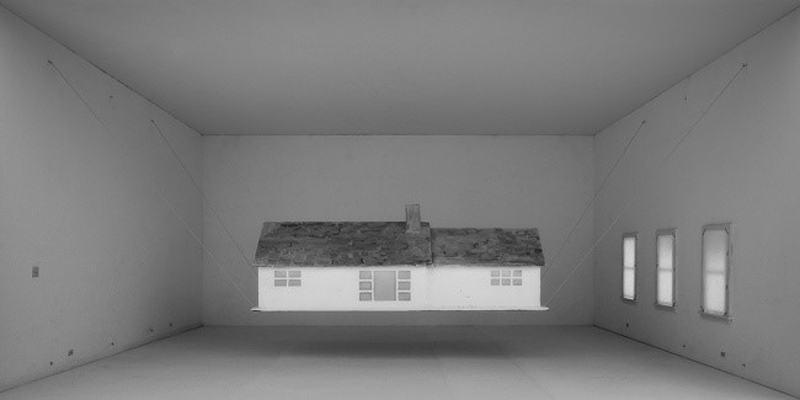

Nic Nicosia, About May-August (Whitehouse #3) (2014). Courtesy of JHB Gallery.

You haven’t had a traditional brick-and-mortar space since 1995. How did that transition impact your work?

Essentially, I think we are considering two distinct changes: the differences between private and public exhibition spaces and how the functionality of the business has changed as a result of being in a private space. Obviously, we’ve shifted from the rigorous exhibition schedule that we began with—mounting 10 exhibitions per year—to a more intimate viewing space. We dedicate our time to meeting or scheduling appointments with our clients, curators, and collectors who appreciate the intimate nature and more personal approach to discussing the works and the artists’ practice.

Have you considered moving back into a public space again?

We have re-considered a public exhibition space, however, given the transition of the current art market to a more global focus with an interactive platform, the internet has provided JHB Gallery with a broadened international audience. We also continue to collaborate with alternative exhibition spaces, as well as museums and university galleries.

Ellen Carey, Caesura (2017). Courtesy of JHB Gallery.

What is your relationship to art fairs like, especially photography-specific ones? How important are they to your business?

I support the art-fair model and have come to value the opportunity they provide in promoting artists and curatorial ideas. Fairs provide access a wonderful network of people and a generative critical discourse.

What trends have you noticed in the art photography market recently?

Generally speaking, we have seen a shift towards thinking about how the medium of photography functions as an extension of space. And with this, the photographic vocabulary and the visual boundaries, as formally or traditionally understood, continue to be expanded. That said, I don’t think we are necessarily influenced by “trends” in the photography market.

Yuki Onodera, 12 Speed – CO No. 11 (2008). Courtesy of JHB Gallery.

Many of your artists—especially those being shown at AIPAD, such as Ellen Carey, Robert Davies, and Amanda Means—make unique prints. As a dealer, how important is “uniqueness” for you? Reproducibility is one of the characteristics that distinguishes photography from other mediums, but it also lessens the value of the product.

Essentially, whether it be a “unique” print or an editioned series, each work is valued as any other artwork would be. For example, if an edition is sold through, the price of the work increases toward the final print, placing more monetary value and provenance on the final work. If the edition aggregate is larger than, say, 25, then it changes the way we understand the work as well as its value.

Many of the artists I represent played an important role in the development of contemporary photographic artwork from the post-modern movement of the early 1980s to the present day. They were working at the forefront of photography, creating fabricated images, conceptually based imagery, and process-based or camera-less work; they used the 20 x 24 Polaroid and were heavily influenced by technology, employing non-traditional strategies of creation and installation, and used a variety of alternative media.

These photographers alter the issue of content and instead focus on the physical process of making images using photographic processes. They question the traditional notions of photographic reality, challenging the viewer’s intuitive responses and demanding a new way of negotiating a photograph—as both an image and an object.