‘I Use Sculpture as a Kind of Wheelbarrow of Meaning’: British Artist John Isaacs on His More-Is-More Approach to Sculpture

Artnet Gallery Network

Consider it an exhibition decades in the making.

British artist John Isaacs first rose up in London among the Young British Artists of the 1990s and, in the years since, has cultivated a dynamic practice that draws on science and poetry, taps into motifs both ancient and contemporary, and crosses mediums with abandon. Perhaps his most recognizable works are his sculptures of distorted bodies and body parts that border on the grotesque. Now, the artist’s first solo show in Geneva—”This is the Place” at Artvera’s gallery—is pulling together an eclectic cross-section of the artist’s output over the past 20 years.

Recently, we caught up with Isaacs, who shared his thoughts on our culture’s obsession with beauty, the transformation of his work over the years, and how to hold out hope in our current climate of doom.

John Isaacs, Untitled (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

The works on view in this exhibition date from 2003 to 2019. How were the works chosen and do you think they show the arc of your career?

The idea was not to make a retrospective… the idea was to make the most comprehensive and interesting exhibition from what was available to us, for a public that probably knew very little of my working practice. Artvera’s is purposely not the typical white space type gallery so I had to take that factor in mind as well, when constructing the show. We wanted to present a selection of works, that reflected the recurring ideas and intentions (one might even say obsessions) that inhabit most of the objects I create.

How do you see your more recent works in relation to your works from the early 2000s?

I don’t think my intentions have changed. I have always been interested in exploring the space between the poetics of meaning and the realities of material. I make all kinds of objects and use all kinds of materials because I find that personally interesting, in that it creates a larger visual and physical landscape. For many, the artistic intention is to purify a sentiment, but I always felt this to be a myth, an absurdity, to trust in some empirical “truth.” My feeling has always been to take something simple and load it with everything possible. I use sculpture as a kind of wheelbarrow of meaning, capable of taking on all of its surroundings, and, alternately, to be crushed by its environment. However, I have to say, my more recent works are less directed towards one specific meaning than the earlier works. I feel the need to work more intuitively now. The question has shifted from what to why.

John Isaacs, The Cyclical Development of Stasis (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

Your works often incorporate elements of the body, but the figures are distorted, fragmented, and often grotesque. What do you feel you can express through the imagery of the body?

All art, all architecture, all fashion is about the body. All human activity is measured by the body. The body doesn’t need to be represented to be present—the physical border between self and the other is the visible surface, but this is simply a geographical point, as we are not defined solely by matter, but by emotions, and, one would hope, by empathy. The fragmented elements of my work are a visual reminder of the incomplete—broken, fragmented bodies are more a reflection of self than the complete body and, thus, a better mirror. Of course, these aspects of my work are often what people focus on, as though I make “monsters,” and I am well aware that society itself is currently in love with the beauty of aesthetics, but in the end all we are really looking for in art, in life, is a place for our self, our selves, a home. I’m more interested in finding the missing pieces of our identity which are felt to be there, but not yet present.

Your titles are often poetic, elusive. How do you see these titles in relationship to the works themselves—or, in other words, what is their intention?

If something appears to be a very specific thing, then it might remain locked in this identity. Titles are a way to free the work from its form and bring it into another plane of existence. For me, a title is the opposite of a definition and should place the mind in a conflict with the eye. The specifics of the actual object or the title in itself isn’t as important to me as the way in which they can be released into another context. The titles are there to remind the viewer of the philosophical value of the artwork, to guide his reflection or, on the contrary, contradict it. The very opposite of sticking a needle through a butterfly and pinning it to a board.

John Isaacs, The Architecture of Empathy (2019). Courtesy of the artist.

The gallery describes your work as a mix of “seductive optimism and abject pessimism.” Can you speak to that?

Well maybe that’s just a reflection of the world at large, right? I mean, look at the current daily diet of [Greta] Thunberg and [Donald] Trump. I’m just a product of the fucked up world that we live in, dreaming of a pristine wilderness while being given every technological chance to watch it vanish. We are all witness now to epic images of apocalypse from raging fires, swarms of locusts, and now, the new plague, not to mention all the usual daily shit going on from human conflicts, vested interests, natural habitats under threat, new continents built of plastic, the list does actually go on and on.

We can all agree that there is a lot to be pessimistic about when you look at the overall greed and bullshit perpetrated on a daily basis by humankind, a lot to leave one feeling powerless and desperate—in fact, it’s safe to say that the “seductive optimism” aspect is really shaking in the shadows of all this darkness these days, but one must never let go of hope.

I do have children, I do want to see a future, and part of that is to shine a light from a good place into the dark. The real “beauty” in art, it’s real role is to seduce people back from the zombie sleep of daily life, to remind people of where they are and what they are surrounded by, where they come from and what they could be, to be re-sensitized to the human race.

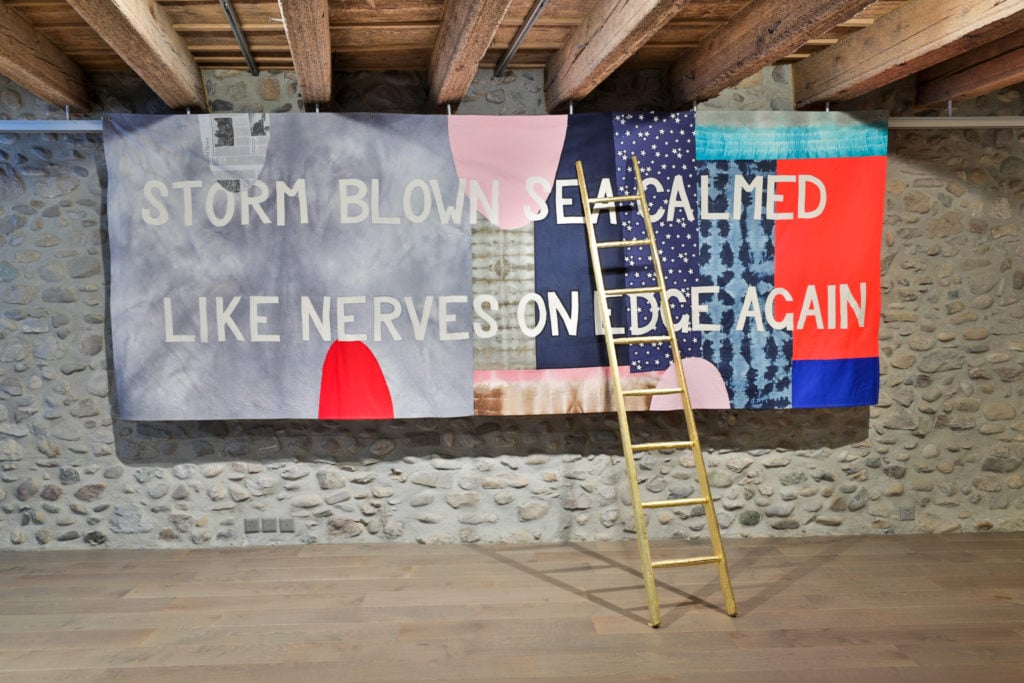

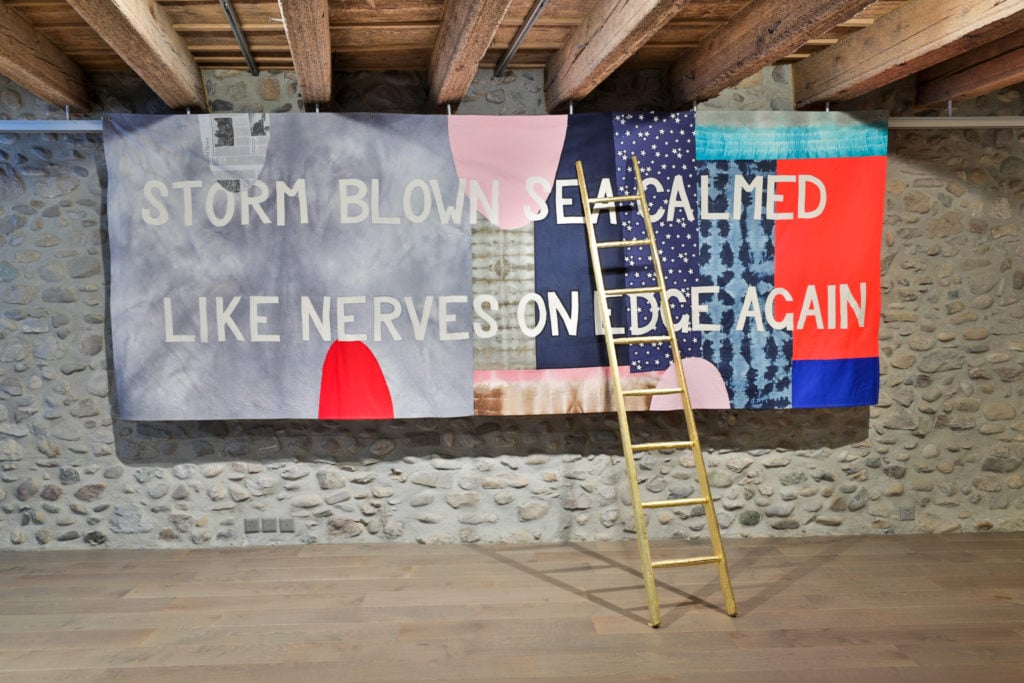

See images of “John Isaacs: This is the Place” below.

Installation view of “This is the Place,” 2019. Courtesy of Artvera’s.

John Isaacs, Things That Can Be Are That Which We Know (2011). Courtesy of the artist.

John Isaacs, Untitled (2018). Courtesy of the artist.

John Isaacs, This is the Place (2016). Courtesy of the artist..

“John Isaacs: This is the Place” is on view at ArtVera’s in Geneva through February 15th.