José Parlá on a Changing Hong Kong, His New Exhibition, and Why He’s Interested In What’s Falling Apart

Artnet Gallery Network

Miami-born, Brooklyn-based artist José Parlá finds walls fascinating. Specifically, the idea of walls as a place for “collective memory,” be they the painted walls of an ancient cave or the walls of a New York City subway tunnel, plastered with torn layers of advertisements.

Hong Kong, a city Parlá had been visiting for the past fifteen years, has long held a particular interest for him, given its mix of old city and new development, pulled between Chinese culture and its British colonial heritage. “Hong Kong makes you want to explore,” said Parlá. “It’s full of textures.”

Now the city is hosting the fittingly titled “Textures of Memory,” a two-venue exhibition of Parlá’s work spread between the Hong Kong Contemporary Art (HOCA) Foundation and Ben Brown Fine Arts. Recently we caught up with Parlá to talk about Hong Kong, why city walls still fascinate him, and the politics of deterioration.

Installation view “Textures of Memory,” 2019. Courtesy of Ben Brown Fine Arts.

Your paintings and sculptures have long explored the layering of history that happens over time in urban spaces. What interests you about that and what does “Textures of Memory,” the title of your current exhibition, mean?

Since I was very young I’d been painting on walls, but also photographing them with my brother Ray and documenting the environment around them. The decay of old buildings, the kind of atmosphere that surrounded us in Miami and then New York, inspired us to make art. Walls were a way of connecting me and other artists I know with history, including art history going back to cave paintings.

The concept of “Textures of Memory” is not really about my work and my self expression. It’s actually more about the collective memory that is embedded in city walls and psycho-geography, and how walls around the world tell stories about different local places.

Dieter Buchhart curated the exhibition, which is spread between Ben Brown Fine Arts and the HOCA Foundation, which are just a few blocks apart from each other. How did all these pieces come together?

HOCA Foundation had reached out to me about the possibility of doing a project, and I introduced them to Ben Brown. He’s from Hong Kong and has had a gallery there for a really long time. I’m the kind of person who likes to introduce people, create connections. Dieter had written an essay about my work a few years earlier and we had become acquainted with each other’s work. I ran into him on a trip to Hong Kong and mentioned the exhibition to him. After talking for awhile, I invited him to curate and the conversation really started. He visited the studio in New York while works were in progress and we had a really great dialogue. He got to see my show in New York, “Anonymous Vernacular” at Bryce Wolkowitz Gallery. In the new book, Textures of Memory, there’s a really great conversation between us.

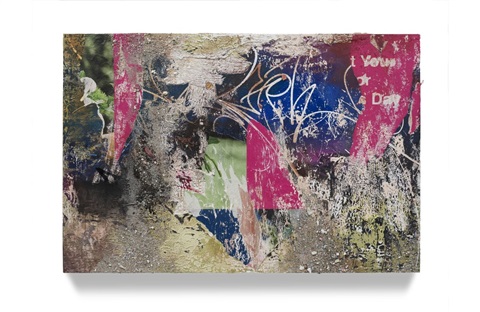

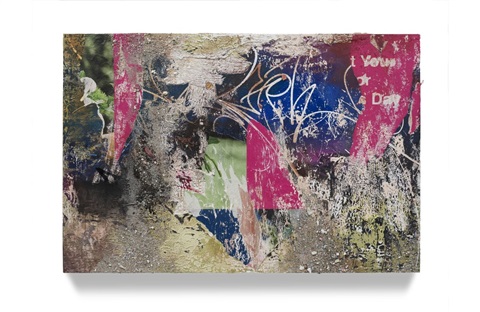

José Parlá, Anywhere Fragment (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Ben Brown Fine Arts.

Some of the works in the exhibition are inspired by Hong Kong. When did you first visit Hong Kong? What’s your relationship to the city?

I first started traveling to Hong Kong in 2004. I spent a lot of time working in Tokyo prior to that and had friends from Japan and also from Korea who invited me to come. I have this habit of exploring cities and I started photographing Hong Kong right away—it’s a very photogenic city. Hong Kong makes you want to explore. It’s full of textures. In 2004, even more so than now, it had a lot of older buildings juxtaposed with new buildings. I was interested in trying to understand how the city works: There are alleyways and peaks and corridors. It goes up the mountains and down.

Anywhere I am, I am always looking at what is written on the walls, in the posters, seeing what was ripped. In Hong Kong, I encountered the works of the King of Kowloon, an artist who was writing political messages on walls in Chinese calligraphy. It was really beautiful work and very dense. He would cover a wall with what looked like an entire manuscript. The city was really inspiring and I started making works about it right away.

I visited Hong Kong for about ten years straight. Over time I developed a relationship with the city and came to know it. The exhibition has some pieces inspired by Hong Kong, but it also has pieces that are in conversation with different cities, from New York to Tokyo, London, and Havana.

José Parlá, Without Roots the Trees Won’t Grow (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Ben Brown Fine Arts.

You’ve been based in New York for 25 years, but cities around the world continue to influence your work.

There is always something very neat and very special about each city. Especially going back 20 years before this big wave of globalization, before high-speed internet, it was a different world. I have one foot in the analogue and one in the digital. I was a witness, like many people of my generation, to this transformation of the world and of cities. I am interested in trying to grasp that energy in my paintings and in my sculptures. I feel as if, through painting, you can tell a story that’s about feeling. How does each city make you feel? The colors are representative of each city. In a sense, I’m creating memory documents, layers of paintings. My studio has always been something like a laboratory to try and understand the context of urban experience throughout different parts of the world.

José Parlá, Verona Street Redhook (2019). Courtesy of the artist and Ben Brown Fine Arts.

Do you remember the first city wall that captured your attention?

I started making art—and especially started making art on walls—at a time when I was not developed as an adult at all. From the age of 10 to 15 years old your mind is constantly changing and absorbing at such a rapid pace. What I really noticed was the environment where I was started painting. My parents had immigrated to the United States from Cuba in the 1980s. Society was at the same time all new and it was deteriorating all around us. You could see the deterioration of walls in New York. Things were being demolished all around us. The subway systems were decaying. The Bronx had been burnt down by fires.

What intrigued me was how in such a place as the United States, where there was so much money and which is a place where so many people come to make a better life for themselves, it was all falling apart. It still is. Around the world, I look for this evidence of things falling apart.

What do you see as the reason things were or are deteriorating?

The facade of a building crumbling has a political connection to how things are run. What are the economic circumstances of those political systems? My work has always been connected to how I see and observe society and these questions about authority and systems lead the paintings into a philosophical realm—questioning the system but also looking at the details of neglect that affect education and so many aspects of how we’re living our lives today. The work is cemented and rooted in these thoughts.

Installation view “Textures of Memory,” 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Hong Kong Contemporary Art Foundation.

How does language influence your work? Sometimes you incorporate words into your own work, though obscured. Earlier you mentioned the work of the King of Kowloon in Hong Kong. Does knowing a language or not knowing it inform your work at all?

When I first encountered the work of the King of Kowloon, I had no idea who made it or what it was. I just knew that there was something there. I cannot read Chinese, but I could read the feeling. I felt there was something really urgent in this person’s work. I didn’t know the person’s age, or whether it was a man or a woman. I didn’t have any of that background. But I didn’t need to know the details to know that I had been impacted.

It’s like encountering a lost tablet from 10,000 years ago in Mesopotamia and archaeologists try to decipher the language. To me, that’s still happening. In my work, I try to develop a language, whether painterly, abstract, or actually using written language that is universal. It’s not meant to be read; it’s not meant to be legible. I camouflage language on purpose so that people from any culture could feel the work rather than try to read it.

I equate that to the way you would feel about a Mark Rothko painting. Sometimes when you’re looking at a billboard and it’s totally falling apart you can only see fragments and layers of advertising. When you have these little bits, some of them years and years old in the back with newer ones in the front, all together it looks like an abstract painting. You feel all these colors. They resonate and vibrate. Everyone has their own experience that you take away and that is personal.

“José Parlá: Textures of Memory” is on view at Ben Brown Fine Arts through November 4, 2019 and at Hong Kong Contemporary Art Foundation through October 11, 2019.