Chinese Contemporary Artist Li Tianbing Fuses Joy with Protest in His New London Exhibition

Katie White

On December 13, 1978, two years after Chairman Mao Zedong’s death, Chinese political leader Deng Xiaoping gave a speech that envisioned a bold new future for the ancient nation, one in which the isolationist country would become an active arbiter of economic relations with the West.

This “opening up” of China had far-reaching and almost immediate cultural consequences as Chinese artists began to deviate from sanctioned Soviet Realist aesthetics into new modes of expression. Considering his work, it is perhaps unsurprising that contemporary painter Li Tianbing (born 1974) came of age in China during this period of upheaval, economic transformation, and cultural re-imagination.

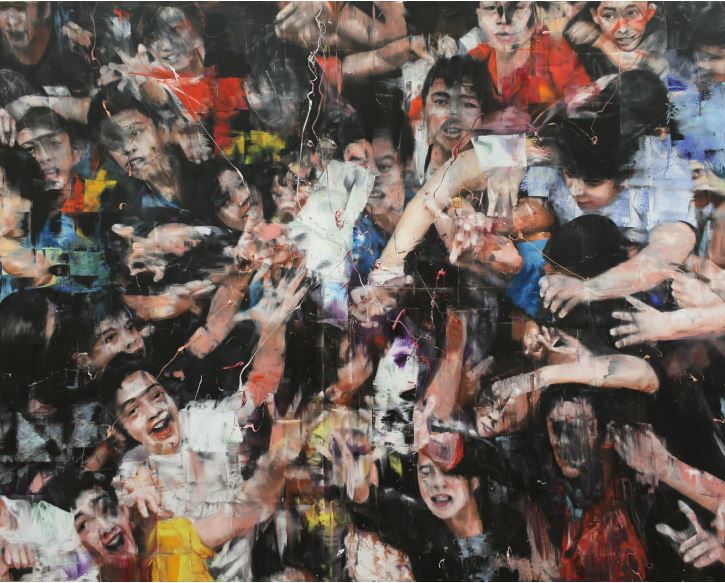

Installation view “Urban Scene,” 2019. Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery.

Li Tianbing considers himself part of a generation of Chinese “New Wave” artists, who struggled to bring art-making out of the realm of political messaging. His large-scale canvases have often personally confronted issues of isolation in post-socialist China, which stemmed from the nation’s “one-child policy,” established in 1980.

In “Urban Scene,” the artist’s new exhibition at London’s JD Malat gallery, Li Tianbing has turned his inquiries toward public spectacles such as mass protests unfolding in China today.

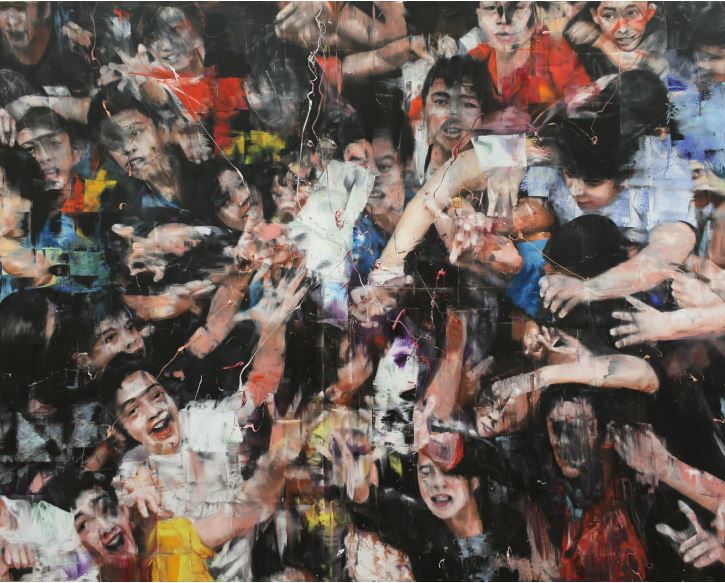

Installation view “Urban Scene,” 2019. Courtesy of JD Malat Gallery.

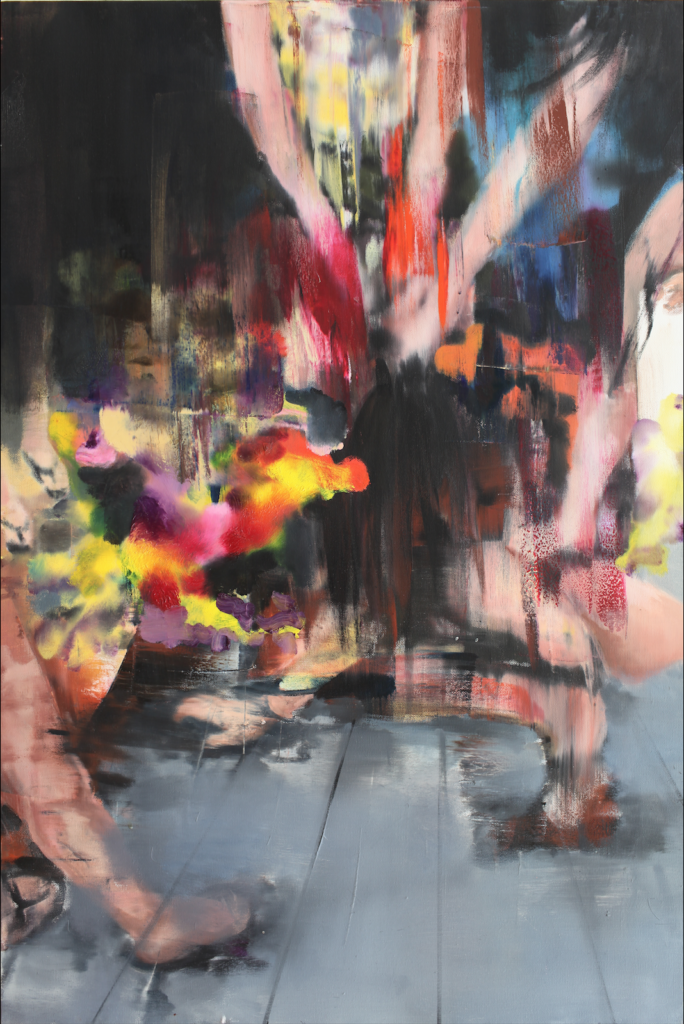

Many of the canvases in the exhibition are marked by strong use of red, the color most closely associated with the Chinese Revolution. The imagery—often of jostling crowds—is chaotic and contemporary. In Pose for Photo (2018), onlookers clamor for a cell-phone picture of a silhouetted figure, a scene that uncomfortably echoes the frenetic tumult in nearby canvases such as Looting Empty (2018) and On the Ground (2018), which depict protest and violence. There is almost a joyfulness to these scenes of bodies colliding with one another, and they could, at first glance, be mistaken for images from a music festival.

For Li Tianbing, these brief moments of street encounters and political insurrection are a form of resilience against the anti-globalist, nationalistic movements that have risen in China and around the world. The artist has commented on the worrying rise of enthusiasm for Maoist ideology, even among artists, which he sees as dangerously supporting the so-called “stability maintenance system”—which in fact consist of legal measures enacted to repress free speech. “The situation is like a volcano ready to erupt at anytime,” he says. “People become anxious and hysterical.”

In 1996, Li Tianbing moved to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts, and there began to form his unique synthesis of Eastern and Western painting techniques. Though painting primarily in oil, he has remained deeply informed by Chinese traditional painting, particularly the Xieyi freehand style of calligraphy, which values rapidity, control, and gesture. His quick, expressive, and purposefully blurred images create a sense of urgency, and the artist has mentioned his interest in Futurism, which also rejected the past in celebration of violence and youth. But Li Tianbing’s images seem less a mimicry of speed and industry. Instead, they desire to hold still a brief moment in rapidly changing world.

Li Tianbing, On the Ground (2018). Courtesy JD Malat Gallery.

Li Tianbing’s new exhibition “Urban Scene” will be on view at JD Malat Gallery in London through June 15, 2019.