On the 50th Anniversary of a Landmark Cybernetic Art Show, Mayor Gallery Looks Back at Pioneering Computer Artists

Artnet Gallery Network

In 1968, the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London mounted “Cybernetic Serendipity,” the first major exhibition of cybernetic art—that is, art made with machines and computers, in particular. The influential show, curated by Jasia Reichardt, demonstrated that computer art has been around almost as long as modern computers themselves.

In honor of the 50th anniversary of the landmark exhibition, Mayor Gallery in London has mounted a computer art-themed show of its own. Titled “Writing New Codes,” the exhibition brings together three pioneers of computer art— Waldemar Cordeiro, Robert Mallary, and Vera Molnár—with a selection of works that date from 1969-1977.

The term “computer art” was coined in the early 1960s, though at that time, and for many years after, few artists were actually making it. It wasn’t until later in the decade that many of the medium’s early innovators were able to gain access to the machines.

As an art form, it evolved from Minimalism, Constructivism, and concrete and Op Art—work that was the product of a set of predetermined conditions, rather than human impulse (such as Abstract Expressionism).

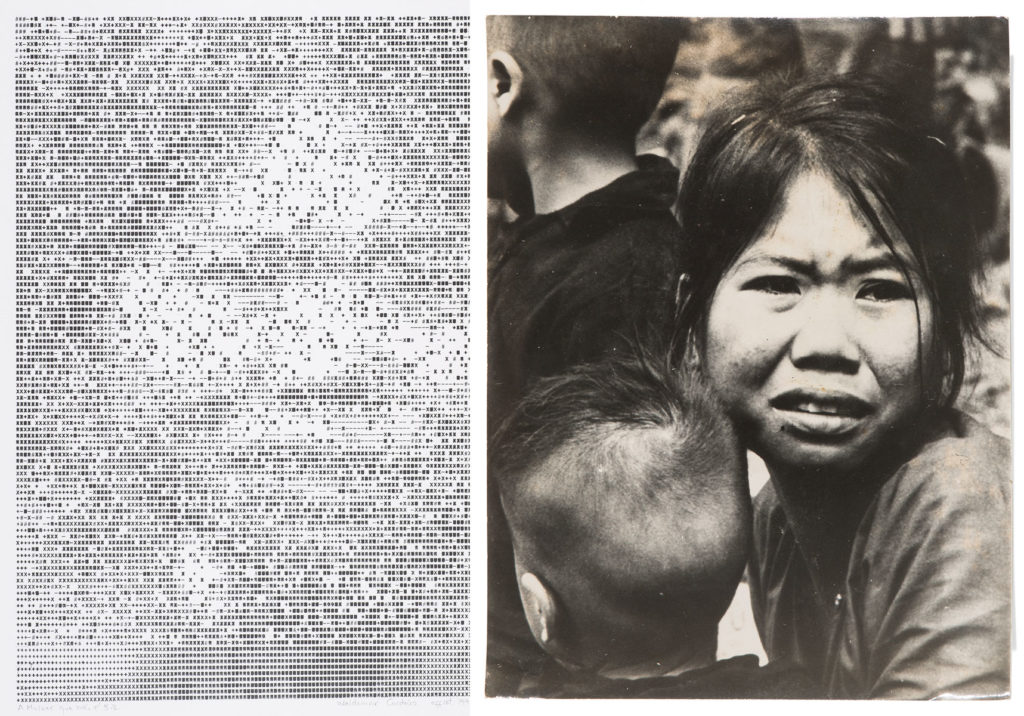

Left: Robert Mallary, Incremental series (1970). Right: Robert Mallary, Incremental series (c.1972). Courtesy of Mayor Gallery.

Though they were each experimenting with computers, Cordeiro, Mallary, and Molnár’s work shared few aesthetic similarities. They also lived in vastly different parts of the world. Cordeiro was born in Italy and immigrated to Brazil in his early twenties. He brought a photographic approach to the medium, translating politically-charged images through programmed data.

Mallary, an American known for his Neo-Dada “junk” sculptures, was drawn to the machine for its strict mathematical parameters, producing computer-plotted drawings inspired by Sol LeWitt. His work Quad I (1968) was the first digitally modeled sculpture—a precursor to contemporary 3D printing—and was included in Cybernetic Serendipity. (A follow-up work, Quad III, is included in the Mayor show.)

Meanwhile, Molnár, a French artist—and the only one of the three still living—was developing complex systems for image creation years before she had access to machines that could carry them out for her. She thought of herself as a kind of computer—a “machine imaginaire,” as she put it. In the early 1960s, alongside artists François Morellet, Julio Le Parc, Jesus Rafael Soto, and Victor Vasarely, Molnár helped found the Research Group for Visual Art (Groupe de Recherche d’Art Visuel), a collective that advocated for non-objective forms image-making. She turned to computers in the late ‘60s, producing drawings of repeated geometric shapes dictated by algorithms.

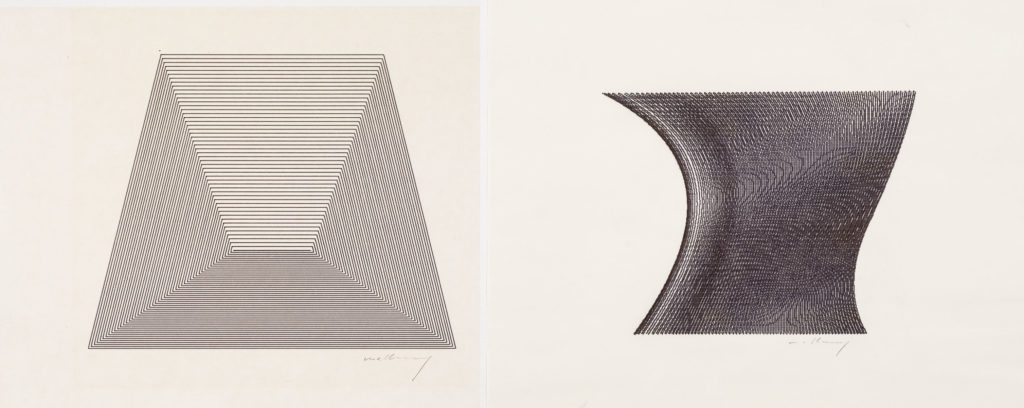

Left: Vera Molnár, Untitled (1972). Right: Vera Molnár, Untitled (1974). Courtesy of Mayor Gallery.

However, despite their differences, they each shared an interest in the computer for its unique ability to translate the creative process. This understanding of the computer’s role resonates with the way we value its function today, as a means of connecting people all over the world.

“It was a new, efficient way for them to communicate what was happening in their brains,” says Christine Hourde, a representative at Mayor Gallery. “The work was already in their imagination; using computers allowed them to get their brains onto the paper quicker than going through the hands.”

Given the prevalence of technology today, it’s difficult to comprehend just how laborious and radical this work was at the time. Computers were very large—often room-filling—and were capable of just a fraction of the processing power that the most basic consumer machines have today. They were often located at research facilities and schools and required engineers and technicians to assist in use. Algorithms were written manually, and fed into the computer via punched cards or paper tape.

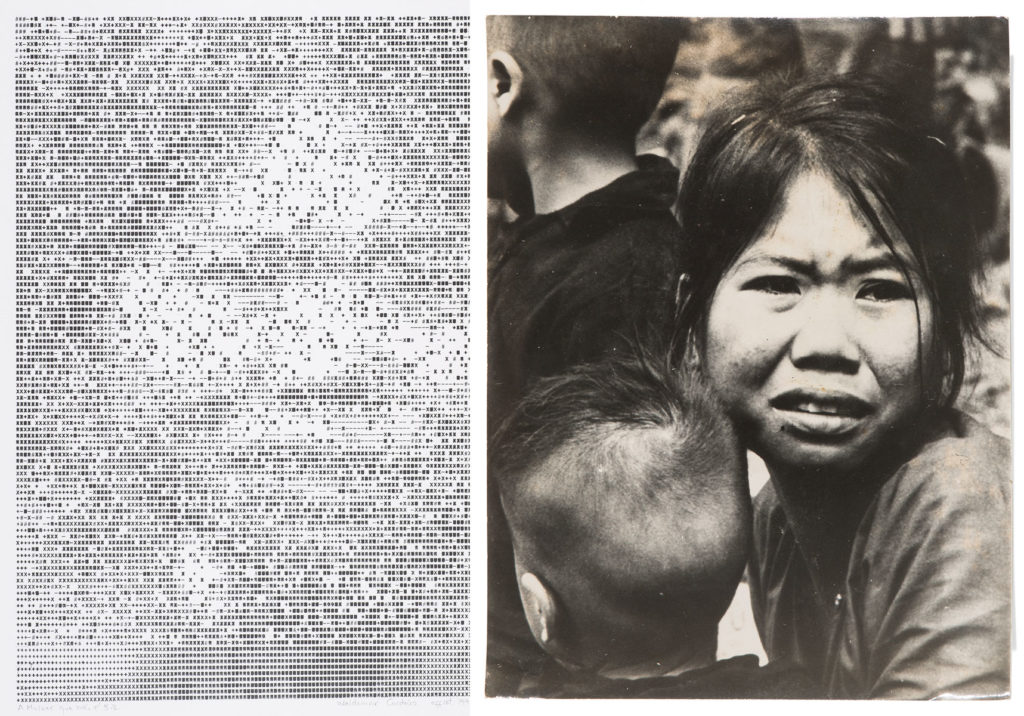

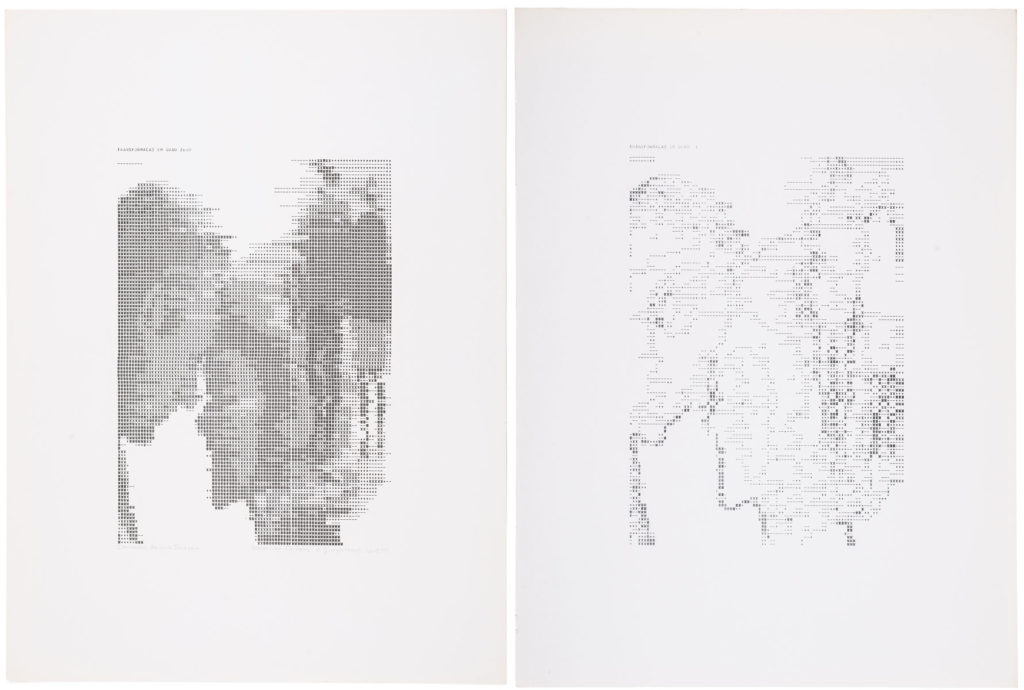

Left: Waldemar Cordeiro, Derivatives of an image degree 0 (1969). Right: Waldemar Cordeiro, Derivatives of an image degree 1 (1969). Courtesy of Mayor Gallery.

“It’s easy to understand it now because it’s everywhere,” says Hourde. “Everyone uses cell phones and Instagram. We have access to images all the time, so we understand how it works. But that was far from the case then.”

Indeed, it’s partly because of these early artistic experiences that today we take for granted computers as an instrument for creativity unto themselves.

“Artists like Cordeiro, Mallary, and Molnár made these works for the general population, for people to get it straight away. They used a visual language that didn’t need explanation. The people who didn’t understand abstract art at the time—it was made directly for them.”

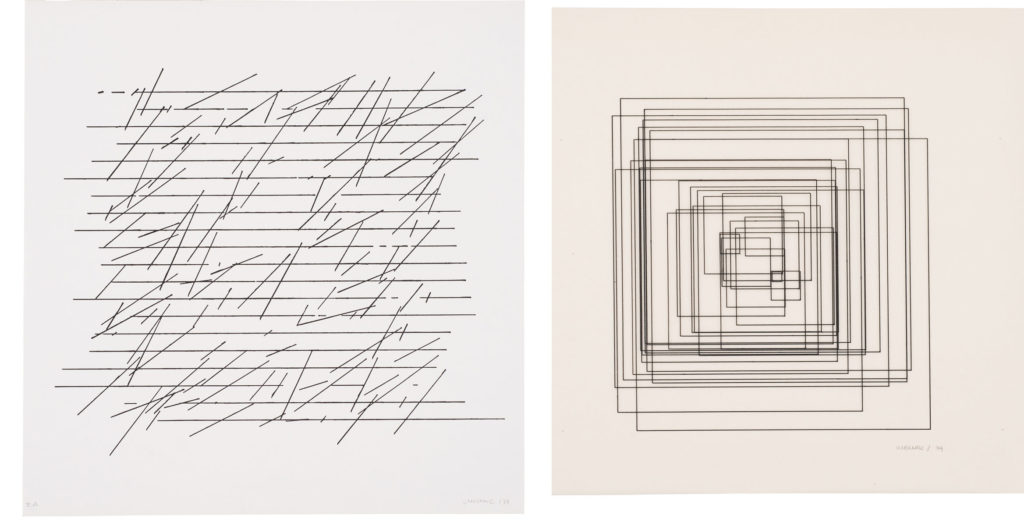

Installation view of “Writing New Codes,” Mayor Gallery, 2018. Courtesy of Mayor Gallery.

“Writing New Codes” is on view at Mayor Gallery through July 27, 2018.